Will Private Equity Spark The Next Crisis?

Dan Primack of Fortune reports, Ben Bernanke threatens private equity:

But fears of Fed tapering are overblown and this could be a brief respite before dividend recap activity picks up again. Still, there are clear signs that private equity activity is slowing, especially in Europe. As discussed in my last comment on visibility and the clearer trade, there are plenty of reasons to be concerned.

There are also reasons to be concerned about the leverage private equity firms have taken over the last few years. Jenny Cosgrave of Investment Week reports the Bank of England worries that private equity could spark the next wave of the crisis:

Below, David Rubenstein, Carlyle Group’s co-founder and co-CEO, speaks with The Wall Street Journal’s Financial Editor Francesco Guerrera.

Mr. Rubenstein says that there isn’t a bubble in global equity or debt markets but that easy money does complicate his private equity business. It tempts buyout shops to load up targets with debt and overpay and it is keeping some potential targets from selling, by allowing them to refinance with the same cheap money.

Some potentially seismic news for the private equity market yesterday, as Yankee Candle canceled a $950 million debt refinancing that would have resulted in a $187 million dividend for owner Madison Dearborn Partners. Not yet reported is that fellow Madison Dearborn portfolio company Asurion Corp. also ended its pursuit of an $850 million term loan to refinance existing debt that comes due in 2017.Yankee Candle's pulled divididend deal may be a sign that the private equity market is turning. Fears that the Federal Reserve may start to cut down on its bond purchasing program have led to debt deals becoming more expensive in recent weeks — and some of them have been pulled altogether.

To be clear, this isn't a Madison Dearborn issue. It's an industry issue.

Private equity has been propped up over the past few years by artificially low interest rates – an environment that has allowed the industry to often escape negative repercussions for its pre-crisis overspend. But now rates are rising in anticipation of next week's Fed meeting and the dreaded "T" word.

"We've all been expecting this for some time, and now it finally seems to be happening," explains a senior private equity exec. "Low rates were fun while they lasted."

To be sure, it's possible that Big Ben won't actually announce tapering of the Fed's bond buyback program – but the debt markets seem to think he will (if not next week, then soon thereafter).

And if that happens, debt refinancing are about to get much, much harder. So will getting well-priced financing for new deals (got to wonder if this has thrown a wrench into Icahn's Dell financing plans – assuming he still has Dell financing plans).

Private equity execs often blanch at the term "financial engineering," but estimates are that firms have done more refinancings for existing portfolio companies over the past year than they've done new transactions (including bolt-ons).

So if a firm really doesn't rely on financial engineering, it shouldn't have anything to worry about. But for everyone else, here's to hoping you either got your refi done already or actually have an operational roadmap for substantial growth...

But fears of Fed tapering are overblown and this could be a brief respite before dividend recap activity picks up again. Still, there are clear signs that private equity activity is slowing, especially in Europe. As discussed in my last comment on visibility and the clearer trade, there are plenty of reasons to be concerned.

There are also reasons to be concerned about the leverage private equity firms have taken over the last few years. Jenny Cosgrave of Investment Week reports the Bank of England worries that private equity could spark the next wave of the crisis:

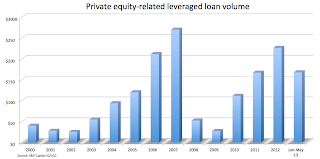

The collapse of debt burdened firms that were bought up by private equity companies before the financial crisis could pose the next major risk to the stability of the UK's economy, the Bank of England has warned.Tim Cross of Forbes reports that private equity sponsors have been busy in the leveraged finance market this year, undertaking some $168 billion of loans through May. That pace would mean a full-year total of roughly $400 billion, easily topping the record $270 billion of LBO loans seen during the height of the pre-Lehman market frenzy, in 2007. But as Cross notes, there’s less here than meets the eye:

These leveraged buyouts (LBO), which are likely mature next year, pose a systemic threat that needs to be addressed, according to the Bank's quarterly update.

The warning from the Bank comes ahead of a major round of refinancing. Some £32bn of LBO debt has to be refinanced in 2014 and 2015, with a further £41bn of LBO debt maturing over the following three years.

"In the mid-2000s, there was a dramatic increase in acquisitions of UK companies by private equity funds. The leverage on these buyouts, especially the larger ones, was high," the Bank said.

"The resulting increase in indebtedness makes those companies more susceptible to default, exposing their lenders to potential losses.

"This risk is compounded by the need for companies to refinance a cluster of buyout debt maturing over the next few years in an environment of much tighter credit conditions," the Bank added.

As there was a surge in acquisitions in 2007, many of these deals will unwind next year, the Bank said: "The average maturity of UK leveraged buyouts' debt is around seven years. Given that the peak in debt issuance was around 2007, there is a significant 'hump' of maturities from 2014."

The study referenced part-nationalised lender Royal Bank of Scotland, which aggressively expanded its strategy in leveraged finance amid a "search for yield" which drove up demand for leveraged loans.

The Bank said under its new regulatory framework, which is coming into effect next month, it would take on the responsibility to protect and enhance the stability of the UK's financial system in order to prevent "future episodes of exuberance" that took place at the height of the boom before the crisis.

Where high profile (and high fee) LBOs and M&A activity drove the market in 2007, with roughly 75% of all private equity-related loans backing LBOs or acquisitions, thinly priced refinancing loans have dominated in 2013, much to investor chagrin. Indeed, so far this year only 19% of sponsor-backed loans support LBOs/acquisitions, while more than half back refinancing of existing debt, often LBO loans put in place not all that long ago. Much of the remainder back credits funding a dividend to private equity firms (institutional investors care little for those loans, as well).

The reason for the spike in refinancings, of course, is borrowing costs, which earlier in the year hovered at or near record lows, and remain attractive to issuers (though things have tightened up over the past few weeks, with a number of proposed loans pulled due to market gyrations).

LBOs, on the other hand, remain few and far between, largely because sellers and buyers remain far apart regarding price, according to LCD’s Steve Miller. There are few signs of a pickup on the near-term horizon, loan arrangers say, though there’s some speculation – or perhaps hope – that deal flow could shift into a higher gear during the fourth quarter as current screening activity reaches fruition, Miller adds.

Private equity investors have other reasons to be concerned. PE Hub reports that private equity firms are sitting on $116 billion of assets trapped in so-called zombie funds that lie dormant but still rake in fees from investors:

Despite the funds being inactive, general partners — those managing the funds — still collect management fees from investors.Zombie funds aren't the only problem. The WSJ reports that private equity firms have an incentive to make returns look good on paper so they can attract investors into their new funds:

U.S. regulator the Securities and Exchange Commission is investigating the use of these essentially inactive funds, which critics say drain money from pension funds and other investors that would otherwise be available to reinvest or return to clients. It is part of a wider SEC probe into the private equity industry as a whole.

Hedge funds, asset managers and other alternative investment vehicles have also recently come under increased scrutiny in both Europe and the U.S. as the public and regulatory backlash since the 2008 financial crisis spreads beyond the banking industry.

The Preqin research — which is based on records of active funds managed between 2001 and 2006 that did not raise a follow-on fund after that time — found that zombie funds were sitting on shares in more than 1,700 companies.

The zombie funds returned less than 40 percent of the capital they paid in, compared with a 99 percent return for all private equity funds raised in 2003, Preqin said.

“No one is a winner when zombie funds are involved and represent a clear misalignment of interests between the fund manager and investor,” said Ignatius Fogarty, head of Private Equity Products at Preqin.

“GPs should be eager to realize investments and return capital to investors so that there is no reputational damage that adversely affects their ability to raise a follow-on fund,” Fogarty added.

Secondary buyouts, a takeover of private-equity assets by another private equity firm, offer a route out of a zombie fund and some fund managers even see buyouts as an investment opportunity.

Last month, Merchant bank Kirchner Group and Crestline Investors Inc., a hedge fund secondary buyer with $7.3 billion under management, teamed up for a joint venture aimed at taking over zombie funds.

Private-equity firms—which have raised $158.7 billion this year through Monday, according to industry tracker Preqin—are audited and increasingly hire consultants to help them value their holdings. Those third parties perform their own analyses but have to rely somewhat on what the firms tell them.Finally, while many private equity firms are struggling, the kings of private equity are thriving. This is why shares of Blackstone (BX), KKR (KKR), Apollo (APO) and Carlyle (CG) are all up over the past year, some significantly outperforming the overall market.

In the process, some private-equity firms appear to juice the returns intentionally to help raise new funds, according to research released in May by Greg Brown and Oleg Gredil of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Steven Kaplan of the University of Chicago.

"Some funds may be trying to convince people that they are better than they really are," Mr. Brown says.

The good news: According to the research, most firms that try to manipulate their performance fail to raise a new fund. That suggests potential investors see through the trick.

The research estimates that those firms inflate their asset values by about 20% before trying to find new investors. Afterward, the estimated values typically fall back to earth. The paper finds that top-performing funds actually tend to underreport returns.

Another paper released in February by researchers at the University of Oxford in England also found that some private-equity funds seem to increase the value of their assets shortly before raising money.

In a statement, Bronwyn Bailey, vice president of research at the Private Equity Growth Capital Council, an industry group, said: "The [Brown] paper clearly demonstrates that private-equity returns are, if anything, being reported conservatively and that investors will not invest in firms that deviate from industry-accepted valuation practices," adding that firms that can't raise new funds will go out of business.

So what is an investor to do?

For one, if you are a high-net-worth investor considering a private-equity fund, sign on only with firms whose funds have investments from major institutions, Mr. Brown says. Institutional investors do their own analyses of valuation methods to make sure a firm isn't juicing its returns, which small investors can piggyback on, he says.

University of Oxford finance professor Tim Jenkinson, one of the authors of the February research, says investors might be best served by ignoring interim returns reported in marketing materials altogether. His research found that such returns have little correlation to the funds' final performance relative to other funds.

Below, David Rubenstein, Carlyle Group’s co-founder and co-CEO, speaks with The Wall Street Journal’s Financial Editor Francesco Guerrera.

Mr. Rubenstein says that there isn’t a bubble in global equity or debt markets but that easy money does complicate his private equity business. It tempts buyout shops to load up targets with debt and overpay and it is keeping some potential targets from selling, by allowing them to refinance with the same cheap money.