Japan's Private Pensions Eying More Risk?

Eleanor Warnock and Kosaku Narioka of the Wall Street Journal report, Japan's Private Pension Funds Eye Riskier Assets:

Why is this important? Because as the hunt for yield intensifies, these huge inflows will lower yields even more. U.S. Treasurys recorded their best week since March last week as yields fell to 2.52%. And the intensifying debate over when the Federal Reserve raises interest rates is little more than a sideshow when it comes to the ability of the U.S. to borrow:

Who do you think is buying all these U.S. bonds? Japanese pensions looking to diversify away from domestic bonds. They are also snapping up corporate debt and private debt, fueling record demand for the leveraged loan market in the U.S. and Europe.

But diversifying away from JGBs carries its own risks, especially since they have been rallying lately, spelling trouble for a resurgent Japan:

When it comes to macro, the euro deflation crisis is what worries me a lot. Moreover, as I stated in my comment on when interest rates rise, there is too much debt and too much slack in the U.S. labor market to see a sustained rise in interest rates. Bond bears will disagree with me but they will be proven wrong once more.

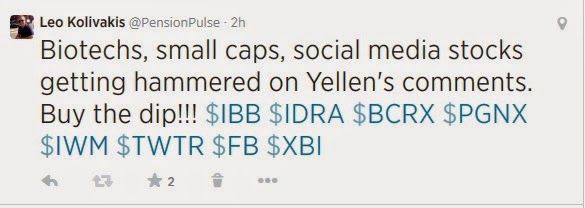

By the way, as I write this comment, I noticed biotechs, social media and small caps are getting hammered on Chairwoman Yellen's testimony where she ironically defended loose monetary policy but warned these sectors are overvalued. Markets didn't like those comments and turned south.

I will reiterate what I wrote last Friday when I discussed whether investors should prepare for another stock market crash. All this noise is just another buying opportunity. Buy the dip in biotechs (IBB and XBI), small caps (IWM), technology (QQQ) and internet shares (FDN) hard and never mind what Yellen says. I'm still in RISK ON mode, and like Twitter (TWTR), Idera Pharmaceutical (IDRA) and many more high beta stocks a lot at these levels. I even took the time to tweet this during Yellen's testimony (click on image):

But everyone is nervous and they got their panties tied in knots because Chairwoman Yellen is warning of bubbles. She hasn't seen anything yet. We haven't reached the melt-up phase in stocks, and when we do, I guarantee you it will make 1999 look like a walk in the park. Enjoy the ride but I warn you, it will be a very volatile and gut-wrenching ride up, and when it's over, prepare for a long period of deflation.

Once again, I thank those of you who have been stepping up to the plate and contributing to my blog and ask many more institutions who regularly read this blog to contribute via PayPal at the top right-hand side.

Below, Masayuki Kichikawa, chief Japan economist at Bank of America Corp. in Tokyo, talks about Bank of Japan policy. He speaks with John Dawson on Bloomberg Television's "On the Move."

And Manpreet Gill, Singapore-based head of fixed-income, currency and commodity investment strategy at Standard Chartered's wealth management unit, talks about Japan's economy and central bank policy. Gill also talks about global stocks, bonds, the U.S. economy and Federal Reserve policy. He speaks with Angie Lau on Bloomberg Television's "First Up."

Japan's private pension funds, which control roughly ¥90 trillion ($888 billion), are turning away from the dismal returns offered on Japanese government debt and instead buying higher-yielding assets, from real estate to catastrophe bonds.In March, I wrote a comment on why Soros is warning Japan to crank up the risk. I was referring to Japan's Government Pension Investment Fund, the world’s largest, which posted a loss in the quarter ended March as Japanese stocks fell, paring its annual gain:

They join the $1.25 trillion public pension fund in moving away from unappealing sovereign bonds where the yield on the 10-year note fell to 0.530% Friday, the lowest in over a year and close to a record low. The shift has been helping spur Japan's property market and bring growth to new investment areas such as bank loans and infrastructure.

It is a switch for the private pension funds, which have for years invested mostly in domestic debt as the country's deflationary environment was good for bonds. Now, worries are growing that buoyed by the Bank of Japan's aggressive bond-buying program, the market may be primed for a big fall as inflation picks up and investors demand higher yields.

Responding to low-yield environment is a challenge for investors globally, and changes to the portfolios by Japanese private pensions are relatively small so far. But with almost a trillion dollars at stake, even small moves can translate into significant inflows or outflows for markets. A survey by J.P. Morgan Asset Management of 127 corporate pension funds released in late June found they had cut Japanese debt to 34.1% at the end of March, the lowest since comparable data became available in 2009 and down from 34.9% a year earlier.

And unlike the giant Government Pension Investment Fund, which is considering adding more domestic stocks to achieve higher returns, the private funds are souring on local equities. Their allocation to stocks at home fell to 11.4% from 11.8%, and they instead bought more foreign bonds, purchased bank loans and invested in infrastructure in the hopes of strong returns to help secure payouts for their pensioners.

Toru Higuchi, who oversees ¥700 billion in investments at the Teachers' Mutual Aid Cooperative Society, added a maximum 2% allocation to both global and Japanese real-estate investment trusts, and the same amount to hedge funds by March. He is now considering investing in private equity and companies deemed socially responsible.

Yoshi Kiguchi, chief investment officer at Okayama Metal & Machinery Pension Fund, which manages ¥45 billion, has increased the weight of shorter-term corporate bonds to 11% from 7% last year. These bonds offer higher yields than government bonds.

The ¥150 billion pension fund of copier-maker Ricoh Corp. last autumn added a 4% allocation to snapping up real estate and infrastructure projects, another 4% to credit products such as bank loans and 5% to nonlife insurance-linked products. These products include securities such catastrophe bonds issued on behalf of insurers that offer significant returns if there are no disasters, but can be wiped out in the event of a catastrophe.

The changes offer a snapshot into how investing in Japan is changing under "Abenomics," a program to bolster the country's long-troubled economy. The central bank has deliberately pushed down bond yields to encourage investors to buy riskier assets, and while some new investments benefit companies at home, others are venturing abroad, where higher returns are more likely.

"We're trying to get our 3% return target with as little risk as possible," said Jun Mori, who helps oversee Ricoh's pension investments. "That means investments that offer a stable return with few ups and downs." The fund returned 4.5% in the fiscal year ended in March.

Pension consultants say money managers who run the private pensions generally prefer investments with a steady stream of income that beats bond yields but with potentially less price fluctuations than stocks. Many don't seek higher risk because their investment targets are relatively low by international comparison amid a low-yield environment. According to consultancy Towers Watson, their target was 2.33% on average in 2012, compared with 7.17% in the U.S.

"Corporate plans aren't worried about funding, so there is no need to take too much risk," said Toru Moriyama, deputy manager in the pension fund management division at one of Japan's largest trust bank, Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking Corp. He said recent gains in local shares and a weaker yen have helped their financial footing.

The funds are still hesitant about domestic stocks, even after a nearly 50% rise in the Nikkei Stock Average since the end of 2012, as many pension managers still can't forget years of poor returns. The benchmark Nikkei Stock Average is still down 60% from its 1989 peak, and has fallen 6% this year, making it among the world's worst performers.

Some managers are also reducing stockholdings because they anticipate more stringent regulatory requirements after banks and life-insurance companies were forced to reduce stockholdings. In addition, more companies are limiting risk in their pension funds as they are required to reflect pension finances on their balance sheets.

"If we don't manage it well, that will have a negative impact on the company's balance sheet…It's not a good idea to do what could drag down our core business," said Yuji Horikoshi, chief investment officer of Mitsubishi Corp.'s ¥280 billion pension fund.

The fund lost 0.8 percent on its investments in the final three months of the fiscal year, trimming assets under management to 126.6 trillion yen ($1.2 trillion), GPIF said today in a statement. Its Japanese shares dropped 7.1 percent in the period. The fund’s annual return of 8.6 percent, buoyed by an equity rally in the first three quarters, compared with a record 10.2 percent the previous year.While the GPIF is increasing its allocation to domestic stocks, Japan's corporate plans are shunning domestic equities and looking overseas, snapping up everything from stocks, bonds, REITs, bank loans, infrastructure and catastrophe bonds, which are in bubble territory.

GPIF has been under increasing pressure to cut domestic bonds in favor of riskier assets since a government panel last year urged an overhaul of its investment strategies. Its results illustrate both sides of the argument over whether the fund should own more stocks: the quarter to March underscores the potential for short-term equity losses, while full-year gains would have been better if GPIF owned more shares instead of local debt that delivered just 0.6 percent.

Why is this important? Because as the hunt for yield intensifies, these huge inflows will lower yields even more. U.S. Treasurys recorded their best week since March last week as yields fell to 2.52%. And the intensifying debate over when the Federal Reserve raises interest rates is little more than a sideshow when it comes to the ability of the U.S. to borrow:

For all the concern fixed-income assets will tumble once the central bank boosts rates, the Treasury Department still managed to get investors to submit $3.4 trillion of bids for the $1.12 trillion of notes and bonds sold this year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. That represents a bid-to-cover ratio of 3.06, the second-highest on record and up from 2.88 in all of last year.In their second quarter economic review, Van Hoisington and Lacy Hunt discuss why global investors are snapping up U.S. bonds:

Table one (click on image below) compares ten-year and thirty-year government bond yields in the U.S. and ten major foreign economies. Higher U.S. government bond yields reflect that domestic economic growth has been considerably better than in Europe and Japan, which in turn, mirrors that the U.S. is less indebted. However, the U.S. is now taking on more leverage, indicating that our growth prospects are likely to follow the path of Europe and Japan.

With U.S. rates higher than those of major foreign markets, investors are provided with an additional reason to look favorably on increased investments in the long end of the U.S. treasury market. Additionally, with nominal growth slowing in response to low saving and higher debt we expect that over the next several years U.S. thirty-year bond yields could decline into the range of 1.7% to 2.3%, which is where the thirty-year yields in the Japanese and German economies, respectively, currently stand.

Who do you think is buying all these U.S. bonds? Japanese pensions looking to diversify away from domestic bonds. They are also snapping up corporate debt and private debt, fueling record demand for the leveraged loan market in the U.S. and Europe.

But diversifying away from JGBs carries its own risks, especially since they have been rallying lately, spelling trouble for a resurgent Japan:

Akira Amari has a good ear for a catchphrase. At a press conference this month Japan’s economy minister assured his audience that the pick-up in Japan’s economy was going according to plan, about 18 months in to the regime of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. “Last year it was a case of ‘Japan is back’,” he said. “This year, it is ‘Japan is on track’.”Count me among the skeptics who don't think the Bank of Japan will attain its 2% inflation target. And I'm not convinced Japan's corporate plans are fleeing their own domestic debt market.

But investors in the country’s Y854tn ($8.4tn) bond market see things differently.

Since the government threw the covers off its revamped growth strategy last month – the so-called “third arrow” of the three-point plan – bonds have rallied, pushing yields down. Meanwhile, the inflation-linked bond market suggests that expectations for average price rises have levelled off at about 1.1 per cent over the next 10 years, excluding the effect of tax increases.

One conclusion is that the government will struggle to deliver on its promises to galvanise the world’s third-largest economy, while the Bank of Japan will fall well short of its 2 per cent target for inflation.

The latest version of the growth strategy – majoring on tax cuts, corporate governance reforms and measures to strengthen the workforce – was much ballyhooed. But analysts note that virtually the entire yield curve has shifted downwards since near-final policy documents began to circulate at the end of May.

Rather than lift expectations for the country’s potential growth rate, it may have done the opposite, says Jun Ishii, strategist at Mitsubishi UFJ Morgan Stanley Securities, likening Mr Abe’s team to Japan’s well-meaning but ineffective World Cup footballers in Brazil.

“While the strategy’s goals are trying to push Japan in the right direction, there is doubt as to whether the administration has the wherewithal to get the job done,” he says.

As for the stalling in inflation expectations, many point fingers at Bank of Japan governor Haruhiko Kuroda, who said last month that core CPI could drop as low as “about 1 per cent” over the summer, from about 1.4 per cent now (minus the effects of April’s consumption tax increase).

To some, that crystallised doubts at the heart of the prime minister’s eponymous “Abenomics” project. Though Mr Kuroda maintains that CPI should resume its progress toward 2 per cent from the autumn, pushed up by higher wages and a narrowing output gap, few share his confidence, says Tomohisa Fujiki, interest-rates strategist at BNP Paribas in Tokyo.

Many bond market participants still feel that, without a boost from yen depreciation or fiscal stimulus – the main effects of arrows one and two, unleashed early last year – CPI has no real reason to climb.

“People are wondering how inflation is supposed to pick up,” says Kazuto Doi, who manages about $20bn of bonds at Western Asset Management in Tokyo. “That is one of the most mysterious parts of Mr Kuroda’s communication.”

There are mitigating circumstances for the recent surge in bond prices. The European Central Bank’s interest-rate cuts in early June have “repriced” other markets via global investment flows, notes Tomoya Masanao, head of portfolio management at Pimco Japan.

Analysts say the picture also has been distorted by the effects of the BoJ’s loan-support programme, which pumped an extra Y4.9tn of liquidity into the market on June 18. In the absence of corporate demand for credit, much has found its way into bonds, say brokers.

“There are very firm, tight conditions,” says Akito Fukunaga, chief yen rates strategist at Barclays in Tokyo. “We haven’t got any inventory left.”

And some argue that it is difficult to come to any firm conclusions about the market’s growth and inflation expectations. Such is the force of the BoJ’s main easing programme – mopping up some Y7tn of JGBs a month, equivalent to more than two-thirds of net issuance of coupon-bearing debt – that current price signals emanating from this thinly traded market are unreliable, they say.

According to Goldman Sachs estimates, 10-year bond yields would be around 1.2 per cent – consistent with a more vigorous economy – in the absence of “quantitative and qualitative easing”, or QQE.

But so far this year the benchmark 10-year yield has spent 50 days below 0.6 per cent – longer than during the extreme demand-driven markets of the summer of 2003 and April 2013, when yields plunged to record lows before rebounding. That hardly bodes well for a resurgent Japan.

“The government’s growth strategy has not yet succeeded in raising growth expectations meaningfully,” says Mr Masanao.

When it comes to macro, the euro deflation crisis is what worries me a lot. Moreover, as I stated in my comment on when interest rates rise, there is too much debt and too much slack in the U.S. labor market to see a sustained rise in interest rates. Bond bears will disagree with me but they will be proven wrong once more.

By the way, as I write this comment, I noticed biotechs, social media and small caps are getting hammered on Chairwoman Yellen's testimony where she ironically defended loose monetary policy but warned these sectors are overvalued. Markets didn't like those comments and turned south.

I will reiterate what I wrote last Friday when I discussed whether investors should prepare for another stock market crash. All this noise is just another buying opportunity. Buy the dip in biotechs (IBB and XBI), small caps (IWM), technology (QQQ) and internet shares (FDN) hard and never mind what Yellen says. I'm still in RISK ON mode, and like Twitter (TWTR), Idera Pharmaceutical (IDRA) and many more high beta stocks a lot at these levels. I even took the time to tweet this during Yellen's testimony (click on image):

But everyone is nervous and they got their panties tied in knots because Chairwoman Yellen is warning of bubbles. She hasn't seen anything yet. We haven't reached the melt-up phase in stocks, and when we do, I guarantee you it will make 1999 look like a walk in the park. Enjoy the ride but I warn you, it will be a very volatile and gut-wrenching ride up, and when it's over, prepare for a long period of deflation.

Once again, I thank those of you who have been stepping up to the plate and contributing to my blog and ask many more institutions who regularly read this blog to contribute via PayPal at the top right-hand side.

Below, Masayuki Kichikawa, chief Japan economist at Bank of America Corp. in Tokyo, talks about Bank of Japan policy. He speaks with John Dawson on Bloomberg Television's "On the Move."

And Manpreet Gill, Singapore-based head of fixed-income, currency and commodity investment strategy at Standard Chartered's wealth management unit, talks about Japan's economy and central bank policy. Gill also talks about global stocks, bonds, the U.S. economy and Federal Reserve policy. He speaks with Angie Lau on Bloomberg Television's "First Up."

Comments

Post a Comment