The Public Versus Private Markets Battle?

Robin Wigglesworth of the Financial Times reports, Private versus public markets is the battle to watch:

But if the dislocation is very severe, pensions will also look into selling private equity fund stakes in the secondaries market at deep discounts, aggravating the problem.

Smart pensions get rid of fund stakes before any dislocations happens. Buyouts reports that Ardian, Blackstone take down $1 bln-plus PSP portfolio:

Below, take the time once again to listen to Mark Machin, chief executive officer at the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, as he spoke with Bloomberg's Erik Schatzker at Davos. Listen to him allude to the public versus private markets dilemma.

Also, Mark Wiseman, BlackRock global head of active equities and BlackRock alternative investors chairman and former CEO of CPPIB, joined "Squawk Box" at the World Economic Forum at Davos to give his best advice on active investing and why he thinks the active passive debate is a false dichotomy. Two smart long-term investors give you great insights here.

There is no shortage of popular bogeymen scaring markets these days, whether leveraged loans or algorithmic traders. But perhaps the least-appreciated dangers are lurking in the shadows, away from the glare of mainstream markets.I discussed Mark Machin's views when I went over Canadian pensions CEOs at Davos 2019. Mark talked about selling "public stuff quite rapidly" because public assets are generally liquid (except in a severe crisis when credit markets seize up).

One of the biggest trends since the crisis has been investors falling in love with “private markets”. There is no clean definition, but essentially the term refers to rarely or never-traded investments far beyond mainstream stocks and bonds, like farmland, real estate, infrastructure, venture capital, direct lending and private equity.

The trend has several drivers, but the biggest is that investor expectations for returns in mainstream public markets have ebbed. Quantitative investment group AQR reckons the classic 60-40 balanced equity-bond fund could over the next decade return as little as 2.9 per cent on average a year after inflation, compared with an average of 5 per cent since 1900. Investment firm GMO reckons real returns could even be negative over the next seven years.

For long-term institutional investors like pension funds, insurers, endowments and sovereign wealth funds, accepting the illiquidity of private markets in exchange for the promise of higher returns therefore makes sense. Indeed, with many struggling to hit return targets — typically 8-9 per cent a year — pouring more money into private markets seems the only option.

As a result, the money has rolled in. Private capital funds of various stripes have raised nearly $5tn just since 2012, according to Preqin. In fact, the strength of fundraising is so extreme that many funds are struggling to find enough attractive investments. Preqin estimates that the amount of committed but uninvested “dry powder” in private capital funds topped $2tn last year.

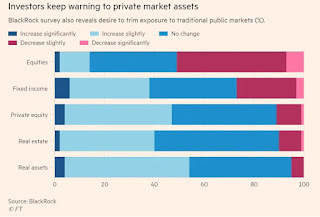

This is a staggering amount, and one that could easily grow further. A BlackRock survey of 230 institutional investors with more than $7tn under management indicated that 51 per cent intended to cut exposure to public equities. But nearly half planned to put more money into private markets while very few planned to trim. No wonder BlackRock has said ramping up its private investing capabilities is a major priority.

However, this raises a host of issues with murky implications for investors, private markets and the broader financial system.

Firstly, investors that have piled into private markets are likely to see returns shrink well below their historical average. Returns on private debt have already been squeezed by the tsunami of money, and the asset class now looks like an accident waiting to happen. Private equity firms boast the biggest pile of dry powder, at $1.2tn, and will also probably see returns fall as competition for juicier deals heats up.

In fact, rather than harvesting an “illiquidity premium” from investing in untraded assets, it now looks more like investors are accepting an “illiquidity discount”. The seemingly smoother returns of private markets — largely a product of how subjective the periodic valuations are — are so attractive to institutional investors whipsawed by volatile public markets that they are paying up for the privilege of investing with private funds, rather than getting paid for the risk of being stuck in untraded assets.

A recent AQR paper argued that the lower risk of investing in private equity was largely an “illusion”, and warned that the ravenous demand had destroyed any illiquidity premium that might have existed. Throw in high fees, and the paper reckons that private equity returns will average 3.9 per cent net of costs and inflation in the coming years — only a sliver above the expected US stock market returns.

Longer term, it raises some thorny questions over the future of public markets. Mainstream bond and stock markets have been the twin engines of modern capitalism, but are they still fit for purpose? And if more money migrates to the less transparent, unregulated private corners of capital markets, what are the implications for financial stability?

Mark Machin, chief executive of the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, recently highlighted one under-appreciated dynamic. In a TV interview at Davos he warned that “if there’s a sudden dislocation in markets, a profound dislocation, people who need the money to pay pensions or to pay other obligations are going to have to sell the public stuff quite rapidly”.

In other words, in a crisis investors flog what they can, not what they want. Given that their mounting pile of private investments will be immensely difficult to liquidate, institutional investors that need to raise money or turn more defensive might have to sell liquid equities and bonds even more aggressively.

CPPIB is widely regarded as one of the most sophisticated pension funds in the world, and is one of the biggest investors in private markets. Mr Machin’s warning is therefore notable, and shows how we are only beginning to grapple with some of the implications of the private market boom.

But if the dislocation is very severe, pensions will also look into selling private equity fund stakes in the secondaries market at deep discounts, aggravating the problem.

Smart pensions get rid of fund stakes before any dislocations happens. Buyouts reports that Ardian, Blackstone take down $1 bln-plus PSP portfolio:

Ardian is buying the bulk of a large portfolio of private equity stakes shopped by Canadian institution Public Sector Pension Investment Board, while Blackstone Group’s secondary team is picking up a few individual fund interests from the sale, sources told...Interestingly, Blackstone’s Private Equity Chief Joe Baratta recently talked to the Oregon Investment Board about the megafirm’s views on the market:

Unlike many firms that over recent years have tried to burnish their commitments to the middle market, Baratta told the pension officials Blackstone is harvesting opportunities in the “unloved” large side of the market.Last week, I discussed why CPPIB and Singapore's GIC took Ultimate Software private, noting this:

“There’s a wide swath of companies in the $3 [billion] to $10 billion market cap of public companies, probably thousands of them in the U.S., that nobody really cares about,” Baratta said.

“They’re not well followed, they’re not well understood, they’re not particularly well managed — that’s where I think we’re going to live over the next five or six years in producing investment opportunities.”

Blackstone also likes to be the first private equity owner of a company, rather than the next in a series of private equity backers.

The other thing to keep in mind is these private equity funds and their investors have so much money that they're increasingly playing in public markets, taking public companies private. For CPPIB and GIC, it's great, it's a co-investment where they pay little to no fees and are able to expand their private equity portfolio very nicely. In other words, it's all about scale, keeping fees low and finding great direct deals (where you can put a lot of money to work) by co-investing with your partners which are top global private equity funds.Blackstone's Joe Baratta just confirmed my suspicions and the trick for public market investors is to find which public companies in the $3 to $10 billion market cap range will be taken private at a nice premium.

Of course, all these public companies being taken private is good news for one group of investors, but others may wonder what happens if private markets take over the world and public markets keep shrinking, offering fewer and fewer choices for investors looking to invest in great companies.

We're not there yet but I view the attrition of public markets as a secular theme that will remain with us for a very long time.

Below, take the time once again to listen to Mark Machin, chief executive officer at the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, as he spoke with Bloomberg's Erik Schatzker at Davos. Listen to him allude to the public versus private markets dilemma.

Also, Mark Wiseman, BlackRock global head of active equities and BlackRock alternative investors chairman and former CEO of CPPIB, joined "Squawk Box" at the World Economic Forum at Davos to give his best advice on active investing and why he thinks the active passive debate is a false dichotomy. Two smart long-term investors give you great insights here.

Comments

Post a Comment