Total Fund Management Part 4: How to Develop a TFM Framework & Process

In Episode 3 last week, we introduced the series roadmap, which helps navigate through the wealth of topics already discussed in almost 300 pages and three hours of presentation material.

The roadmap is organized based on the notion of organizational and investment beliefs about TFM (or why we need TFM), determining what strategies and objectives to pursue to fulfill the beliefs.

As part of the roadmap, we organized all the various insights, conclusions and concerns expressed so far in the series’ episodes in a set of clearly articulated beliefs and corresponding strategies and objectives to pursue.

A central part of the TFM strategy and objective discussion is the investment belief about the path-dependent nature of the pension outcomes. To this end, we encourage those who are new to the series to revisit specifically the conclusions of Episode 2 of "what nobody told you about long-term investing" and the fact that in the presence of liabilities, the long term is a series of short terms. As such, this belief about the path-dependent nature of the pension outcomes requires an investment strategy that explicitly considers the management of the path of the current short- and medium-term achievable returns toward the long-term required returns.

Such an investment strategy needs to be part of a rethought/ renewed approach to asset allocation where it is about outcomes, or what we called an outcome-oriented policy portfolio. This outcome-oriented policy portfolio comprises key pension plan outcomes (level of wealth, inflation protection, contribution rate risk, and liquidity to pay pensions at all times), rather than specific asset classes. The asset classes are only a means to an end (outcomes). What the portfolio holds at any given time maximizes the probability of achieving or maintaining these outcomes with acceptable variations and could change at any point in time given economic and market conditions or other external or internal requirements.

The question then is what the investment objective of such path-dependent, outcome-oriented portfolio management would be. This is similar to the equivalent notion of the portfolio optimization principle introduced by Harry Markovitz. The objective function is to maximize returns at a given level of risk or minimize risk at a required level of returns, or the efficient frontier. But what is the equivalent of the Markovitz efficient frontier when it comes to a path-dependent allocation process? This was the primary focus of Episode 3, which illustrated how to think of this problem by borrowing examples and experiments from physics and computer programming.

To this end, Episode 3 concluded that it is not about long or short-term investing, but it is about how "fast" or "slow" and "safe" when arrives at the final destination (end outcome). We illustrated this with two experiments from physics. Another example was the "daily commute dilemma" where distance (or put in different words, the short- or long-term investing), in a situation of congested traffic does not matter ("congested traffic" being the notion of low or high expected returns). What matters is that one arrives on time and safe at the final destination, even if they took the long road.

We demonstrated that safety is essential because today's pension plans are more sensitive to adverse outcomes than ever. This sensitivity today has doubled since the late 90s. The optimal objective of TFM is also about what decisions one can make about the portfolio today, given what we know with a certain probability about the future and the required outcomes in conjunction with the path-dependent allocation and managing the current achievable returns versus the long term required returns. We illustrated this concept based on the saying that "all roads lead to Rome," but with the "axiom" augmented by the TFM postulate, which road one takes matters.

We also introduce the critical notion of the term structure of expected returns as central to making TFM path-dependent asset allocation decisions.

Isn't TFM just a Tactical Asset Allocation ("TAA") in disguise?

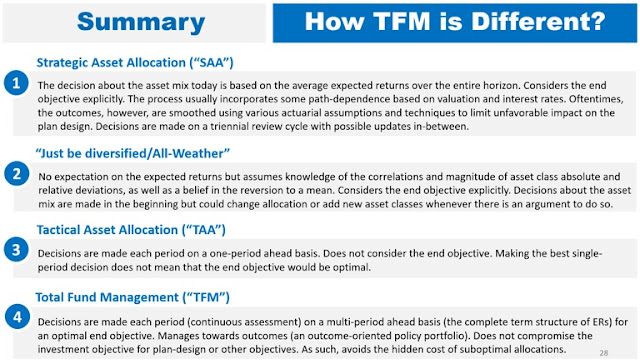

At this point, many of you are probably asking the question, what is the difference between TFM and the typical allocation approaches? Isn't this just a TAA in disguise? And how does it compare to Strategic Asset Allocation ("SAA"), for example, or other "Just be diversified" or "All-Weather" approaches?

Episode 4 provides a highly visual comparison of the difference in these approaches. The comparison is based on the time horizon and the role of the sub-periods for decision-making. Other aspects are how each approach considers the end objective (outcome) and whether the approach incorporates any notion of expected returns and, further, any path-dependence on these returns.

The summary takeaways are presented in the slide below.

The next slides further illustrate graphically some of the points mentioned in summary above related to the decisions at each point of the horizon, the explicit or implicit use of expected returns and how decisions are made throughout the investment horizon.

Some essential observations were also made concerning the SAA and the "Just be diversified," or "All-Weather" approaches. In SAA's case, we can make the statement that we will be holding this asset mix today because we expect these average expected returns over the entire time horizon. There is an explicit expectation of constant average expected returns throughout the investment horizon (a "flat" term structure of expected returns).

A few insider insights on SAA

The conclusion above might bring some disagreement from practitioners. To be fair, typically, the SAA expected returns have a built-in path, which is often valuation-based, for equities and currencies, or path of interest rates embedded in the expected returns. I have witnessed quite a few of these at the various places I have been, so let me tell you some insider insights on this process and why it is essential to talk about it in the context of how different it is from TFM.

Even if there are built-in paths of returns, many of these differences are smoothed out at the end not to create any significant impact on the plan design. Just imagine this, if tomorrow the fund comes up with a zero or, even worse, negative long-term expected returns on equities, what do you think would be the impact on the plan design?

In this case, actuarial techniques and considerations will be used, and these will be either inflation assumptions or some margins for adverse deviation or any other decisions, and this is a significant governance point.

Today, even if one has 100 percent confidence in a zero or negative expected return for equities, these expected returns will directly impact the plan design. This is very difficult to accept by the plan sponsors or the beneficiaries, and the effect is "managed" via actuarial techniques and assumptions. Thus, the investment perspective is overwhelmed by the plan design perspective and possibly disregarded. At this point, it all hinges on the hope and belief for a mean reversion within a reasonable time frame so that the actuarial techniques would work. If there is no mean reversion or a slow bleed, the unpleasant truth shows up and can no longer be smoothed.

Sometimes, the decision of which asset classes to include in the policy portfolio and how much comes from the bottom-up. Usually, some head of an asset class wants to initiate a new strategy or an asset class, often because there is the ability to add value. This now gets into the question of compensation and benchmarks. But let us leave this for some other time. It could also be an area that the asset class wants to explore, or it is about internal politics, centers of gravity and relevance.

This might be a perfectly reasonable argument but it does not mean that the fact that an asset class can add a relative value over the benchmark (what we called local optimality earlier in Episode 1) on a standalone basis is necessarily good for the fund (we called global optimality). It could be that although there is a distinctive case for adding relative value at the class level, however, the asset class may perform worse on an absolute basis or relative to other possible asset classes and strategies.

Also, sometimes, clients need to approve a new product or an asset class. The easiest way for this is to become a new asset class in the policy portfolio. More often than not, the bottom-up process wins, and SAA would need to find a way to incorporate the desired strategy in the asset mix to satisfy the intent. "Finding a way" may include creative correlations, volatility or expected return assumptions, which will bring out the benefits of this addition to the asset mix.

In this example, the investment perspective is overwhelmed by the bottom-up perspective.

Both these examples of the investment perspective being overwhelmed by the plan design perspective, or the bottom-up perspective, could be viewed as examples of the hidden costs we discussed in Episode 1, which ultimately lead to diminishing economies of scale.

There is a more elegant and flexible way to keep the outcomes constant (wealth, inflation, contribution risk and liquidity) via an outcome-oriented policy portfolio and adjust the actual asset mix in a way; it would make sense solely from an investment perspective. It would be a transparent, built-for-purpose, and accountable process with clear costs and benefits.

We spent quite a bit of time on SAA, but it is essential to understand how things work in real life and the constraints of this approach.

No view on expected returns is a view nonetheless

In the "Just be diversified/All-Weather" approach, there are no explicit returns, so there is no term structure.

Now, let us look at the second case, the "Just be diversified" type of allocation approach. In this approach, there are no explicit expected returns. This portfolio management approach is based on the belief that it is best to be diversified if one does not know anything about the future. This still implies that one knows something about the future. Actually, two things. It implies that one knows the future correlations of assets, and one also knows the future magnitude of the changes in assets' value. And the belief that there will always be a mean reversion to a known in an advance mean.

However, correlations are not given. They are an artifact of evolving economic conditions and the headwinds and tailwinds of other technological, environmental and socioeconomic drivers. This is why themes are significant in the portfolio construction context, not only in an investment context, given the extraordinary world of disruption, both technological, societal, environmental, regulatory, you name it, it will be even harder to know what these correlations will be. It would be much harder to assume any stable asset relationships. The same goes for the magnitude. A disruption could swing the fortunes of businesses, sectors or economies overnight with a significant magnitude.

As for the mean reversion, in a disruptive future, mean reversion might be even less likely. Structural changes might take place even if temporary. But who knows for how long temporary is? Look at globalization, travel, office, and many others. Things might get back to the mean, but who knows how long this will take, or the equilibrium mean might change at a different level. Also, the very definition of what the mean is might change as well.

TAA is a single period decision, from today to tomorrow, and there is no direct consideration for the end objective. TAA considers the single best outcome, not the sequence of outcomes across all the periods. You might ask: if we always choose the best single period, will this lead to the best outcome? As we will see in the upcoming Episode 5 with the case studies, using every single period's best path does not lead to the most optimal decision today.

As opposed to the other approaches, TFM makes the most optimal decision today based on a multi-period basis, the complete term structure of expected returns. TFM is a multi-period decision because we can have different expectations about the absolute and the relative expected returns in each subsequent period of the entire investment horizon. This is both different from SAA, where we have constant, absolute and relative expected returns throughout the horizon and different from TAA, where we have only one single period. Thus, TFM is saying that we will hold this asset mix today because we expect these expected returns over the full horizon with a certain probability. Or this is another definition of the path of returns.

We have an (ever-changing) term structure of expected returns at each period in the investment horizon. We are discounting the expected returns at different points in the term structure for each period decision using a path-dependent function (recall the physics and the Rome experiments in Episode 3). Discounting the term structure of expected returns with the path-dependent function allows us to determine the best portfolio we can hold today, maximizing the end objective.

In summary, TFM is distinctly different from other asset allocation approaches. For TFM, decisions are made each period (continuous assessment) on a multi-period ahead basis (the complete term structure of ERs) for an optimal end objective. It manages outcomes (an outcome-oriented policy portfolio). It does not compromise the investment objective for plan-design or other objectives. As such, it avoids the hidden cost of suboptimal allocations.

TFM framework and process

Discussing the difference in the allocation approaches and the role of the term structure of expected returns clears the way to introduce TFM implementation in its first two elements - the framework and the process.

Remember, we started Episode 1 with a slide illustrating that there is no textbook and no blueprint of how to do TFM. If we went through 300 pages and three hours of presenting the foundation of Total Fund Management, it is time to talk about implementation. So, let us close the textbook and look at the blueprints or develop a total portfolio management framework and process. Based on everything we discussed so far, we can define four key objectives of the Total Fund Management investment process and the corresponding strategies to accomplish these objectives. All boils down to the ability to manage "the winding road."

The first element is path-dependent allocation. And to do this, one needs a process that is similar to strategic tilting, or you can find other ways of naming this. The second element is efficient portfolio maintenance or balancing the cost of maintaining the portfolio with the risk of this portfolio deviating from its original version and the return which could be gained or sacrificed by doing so. A proper portfolio rebalancing represents this as a strategy to implement efficient portfolio maintenance. The next two elements are related, and they are the ability to manage downside risk and liquidity and contingency management. The strategy to accomplish this objective is some form of risk mitigation portfolio protocol.

Let us now zoom out and outline some key aspects of the three strategies we just identified to accomplish the four initial objectives.

The first one is portfolio rebalancing, and portfolio rebalancing is most efficient as portfolio maintenance in normal market conditions. However, portfolio rebalancing is suboptimal when there is a pronounced trend, whether a market downturn or a bull market.In a market downturn, what becomes essential is managing everything related to the balance sheet, leverage, liquidity and ultimately, contingency. And this needs to be done within a structured risk mitigation portfolio protocol, which includes monitoring and dynamic downside protection, the ability to have critical stress signals and planned crisis asset allocation and liquid contingency. On the flip side, in strong market conditions, what one needs is a strategic tilting or any form of a cycle and valuation type of allocation. And what is also important is to optimize the leverage and the balance sheet in these conditions.

To do all this, one needs a structured process that integrates market liquidity and economic conditions with valuations to arrive with expected returns and risk conditions and the short- and medium-term horizon. We will look at this process next.

The TFM process

This is the core of the total portfolio process.

It starts with portfolio exposures. The second element is the ability to have a macro and market valuation framework. The third one is the portfolio diagnostic. And the fourth one is when it all comes to making investment decisions.Nothing could be accomplished without portfolio exposures. As simple as it may sound, a key aspect is timely and accurate reporting on critical attributes with country regions, sector duration, credit and so on. Style and factor exposures are also valuable, but a strong foundation for basic but timely and accurate key exposure reporting is needed first. Probably less in the past, but thematic exposures are becoming increasingly crucial for TFM given the disruptive nature of the world today, as they may be a headwind or a tailwind to the conclusions from a broader macro market assessment.

The second element of the investment process is the most critical one because it allows you to link assets to markets and develop absolute and relative expected returns for these assets at different horizons, which is then the basis for the term structure of expected returns.

And at different horizons, asset returns are driven by different forces. Short-term returns are heavily driven by economic and market indicators related to liquidity and sentiment. And the short- to medium-term returns are driven primarily by business, credit and monetary cycle conditions, including tailwind from valuations. The medium-term horizon for three to five years, returns are primarily driven by valuation. And finally, at the 10+-year horizon, the expected returns are driven by a combination of deviation from long-term equilibria, with some tailwind from the valuation.There is an additional aspect of the expected returns that needs to be considered, and these will be the themes because, as mentioned earlier, themes could act as a headwind or a tailwind to the macro or the market signals. And they may impact different horizons as well, so you can have multi-cycle themes, which are kind of mega supercycle trends that play on structural drivers of change. Then, there might be cyclical themes that typically dominate the returns and are seldom repeated in consecutive cycles. And then you can have within-cycle themes, typically early, late- or mid-cycle plays and impacts.

And these could sometimes have a significant impact on the final expected return. So, although the market and the macro conclusions might be suggesting a certain expected return, the impact of a theme could amplify or negate the impact.

The reason for this is that a properly designed macro and market framework would allow you to develop the term structure of expected returns and as we saw the term structure of expected returns, it is an essential requirement for a path-dependent total portfolio allocation process. And besides, if the macro and market framework is appropriately designed, the conclusions about the assets themselves would effectively allow you to develop several risk matrices, which describe the market and economic conditions. And these risk matrices are complementary to the expected returns, and they provide a more aggregate view of the state of the market and what drives this state.

The third element of the investment process is portfolio diagnostic. This is the ability to evaluate the current portfolio versus the expected returns and the risk matrices derived from the macro market framework. So, visually, once you know what your exposures are in the portfolio, you know the market conditions and what it means for the expected returns. Then the product of all this is the ability to diagnose the portfolio. And this now leads to the ability to make decisions.

There are several requirements for an efficient decision-making process. The presentation goes into detail on these, but the necessary conclusion is that there is a need for a structured and disciplined process at the investment committee. The reason for this is that in many cases, you can observe investment committees, even at some of the large funds, for that matter, that does not necessarily have such a structure and discipline process.

And by virtue of this, a lot of decisions are ad-hoc decisions. Ad-hoc decisions are typically made only in a stressed market condition, so when it is about, figuratively speaking, it is about the return of capital rather than the return on capital. So, it is about preserving capital rather than any return on this capital. And this is a problem because this means that a lot of the potential efficiency embedded in the TFM process will not be necessarily realized. And therefore, it becomes, again, one of these hidden costs that weigh in on the efficiency and the effectiveness of the Canadian Pension Model. The fact that there is no well-structured and disciplined process at the investment committee is an implicit, hidden cost to the fund's efficiency. This is why there is a need for an investment process.

Now, sure, an investment process is needed. But it has to be structured and disciplined and most probably data-driven as well, rather than just a discretionary one. And the reason for this is that there is, as everybody knows, there is an information overload. There are too much data and too much noise as well. And it is not easy to know where to focus the energy and time. Also, having a proper process, both structured the disciplined and data-driven, safeguards against cognitive biases, so subconsciously making selective use of data or even feeling pressured to decide by more powerful or more knowledgeable peers at the investment committee.

And ultimately, it is also about accountability and the ability to follow and the ability to look back and look at good decisions and bad decisions and create this evolutionary process of learning from mistakes and certainly probably making new mistakes.

Let us zoom back in on how the macro and market framework we described earlier supports specific investment portfolio decisions at the Total Fund, as illustrated in the next slide.

So, for the first time in the series, we can articulate and visualize the TFM integrated investment process. So, this investment process at its core has the four elements of the decision-making so, exposures, macro and market framework, portfolio diagnostic and decision making, all the elements that we discussed so far. This is the core of the process, but many satellite TF investment processes are linked and draw conclusions from the core investment process. And these processes have mentioned them a couple of times already throughout the series, but here is the first time we put them all on one page in an integrated manner. These are the rebalancing decision, risk mitigation, anything related to strategic tilting or any path-dependent allocation, currency hedging, active risk, balance sheet, leverage, and liquidity.And what is essential is that all these decisions are made in an integrated fashion.

So not just making the rebalancing decision and undoing it through some currency hedging decision or some liquidity decision. Or deciding on the risk mitigation decision, but then offsetting it by some other decision. And it is also a consideration of the cost/benefit of doing one or the other. So, for example, if the decision is to hedge because of exposures, what is going on in the markets, the portfolio diagnostic, the decision is to look at, let us say, equity risk.

The decision needs to be carefully weighed whether this is done through a risk mitigation mechanism, be it, let's say, some form of portfolio insurance, or this could be done through the rebalancing just by increasing the cash allocation, which in certain cases could be an equivalent could be seen as an equivalent option position, or this could be done through the cross-hedging properties of currencies. Again, which way it is implemented is also a question of the impact of the decision or the magnitude of the impact, but also what is the cost of this decision?

Because it might be, you know, a hundred percent impact through the portfolio insurance mechanism, but it is very costly, or it could be an 80 percent impact through rebalancing. Still, it is very cheap as a direct cost, but there is a hidden opportunity cost. And the same for currency hedging, so it is the ability not only to be able to articulate these decisions but also weighed the cost-benefit of these decisions.

And this is what a CIO needs to be able to implement a TFM process. And again, this TFM process is not because it is nice to have. It is all about bringing these second-order efficiencies to the fund to extend the economies of scale rather than just having TFM as a self-centered process on its own. It is a good time now to pause. And zoom out and visualize in a slightly different way the roadmap that we discussed in detail in the previous episode and visualize it through the steps we need to take to move from the investment beliefs to the actual implementation.

In closing, these are the key takeaways from today's episode, how to develop a Total Fund framework and process.

- TFM is very different from SAA, and any all-weather or diversification approach or TAA.

- TFM critically relies on the ability to formulate expected returns at different time horizons or this term structure of expected returns. The path-dependence is the distinct feature that separates it from all the other approaches and allows it to function.

- At its core, the TFM process can formulate absolute relative expected returns at different time horizons as part of a consistent and coherent macro and market framework.

- The evaluation of the TFM exposures given the expected returns and the market conditions, or what we called risk matrices, allow for making critical Total Fund decisions. Total Fund decision making, however, requires a structured and disciplined, data-driven process.

This concludes Episode 4 for today. Episode 5 next Thursday will provide several case studies to illustrate key TFM applications and decision processes.

Let me begin by thanking Mihail Garchev for another great comment on integrated Total Fund Management.

If you have not done so yet, please review all three previous parts of this series:

- Introduction to Integrated Total Fund Management: Part 1

- Total Fund Management Part 2: What Nobody Told You About Long-Term Investing

- Total Fund Management Part 3: When All Roads Lead to Rome

I highly recommend you take the time to read our previous comments and watch the previous episodes in order to get the right foundations.

Once again, the material covered here isn't available in textbooks, consultants don't cover it properly or at all, it can only be produced by someone like Mihail who not only has extensive experience and knowledge, he's also an excellent teacher and it comes across in the clip below.

This week, Mihail had oral surgery and was pretty much out of commission on Monday, so I thank him for taking the time to work on this episode and hope you enjoy it.

Today's episode discusses implementation but Mihail begins with a great discussion on the difference between strategic asset allocation, the all-weather/ diversified approach, tactical asset allocation and total fund management.

Importantly, TFM critically relies on the ability to formulate expected returns at different time horizons and the path-dependence is the distinct feature that separates it from all the other approaches and allows it to function.

As he states: "At its core, the TFM process can formulate absolute relative expected returns at different time horizons as part of a consistent and coherent macro and market framework."

On implementation, he raises a lot of critical issues and states Total Fund decision making requires a structured and disciplined, data-driven process.

I won't provide too much feedback today as I received this comment in the late afternoon but let me give you some good food for thought on why implementing proper Total Fund Management is so critical nowadays.

Earlier today, a friend of mine sent this very long but interested article posted on Seeking Alpha, Money-Printing : 2020 vs 2008.

Without getting too much into it, I replied to my friend:

First of all, she borrowed heavily from my ideas on deflation coming to the US which I wrote back in 2017.

Alright, no problem, she then goes into a long and somewhat technical comment to come to the same point I've been making, namely, the Fed and other central banks are desperately trying to ward off deflation but their policies are only making things worse.

The Fed has succeeded in creating a) Asset Inflation and b) Housing inflation but it cannot control overall inflation which comes from sustained wage gains.

Asset inflation primarily benefits ultra wealthy people which own all the assets but it exacerbates wealth inequality and is ultimately deflationary.

Housing inflation always leads to mania which end very badly with ripple effects in credit markets. So that too is ultimately deflationary.

The central theme I keep harping on for pensions is that deflation is still headed our way.

This means we have not seen the secular lows on long-term bond yields and we need to prepare for a long period of ultra-low rates, possibly negative rates, and with that much lower returns going forward but with a lot more volatility.

I'll talk about this week's market melt-up tomorrow but a week doesn't make a decade and long-term investors know this very well.

There are important structural issues going on out there and those who understand these themes very well recognize why adopting and implementing a Total Fund Management approach is critical at this time.

Basically, anything you can do to add value over a multiple time frames using all the tools at your disposal is critical and can make significant contributions to your pension plan/ fund over the long run.

Anyway, I don't want to confuse anyone, please take the time to watch Episode 4 and jot down notes as I did because there is a lot covered here.

Below, Episode 4 of the seven-episode series "Introduction to Integrated Total Fund Management" presented to you by Mihail Garchev, former VP and Head of Total Fund Management of BCI.

Once again, I thank Mihail for another great episode, hope he recovers swiftly from his oral surgery.

Comments

Post a Comment