Will Private Equity Funds Rescue the Markets?

Wall Street was in a giddy mood today. US GDP figures were revised up, right in time for the Republican National Convention next week. This will surely help bolster McCain's assertions that the economy is just fine (sure it is, especially if you lost track of how many houses you own!).

Falling oil prices also helped stocks soar as fears from Tropical Storm Gustav pushed crude oil above $120 a barrel early today, but prices later fell into negative territory as traders bet the government will tap the Strategic Petroleum Reserve if supplies are threatened.

But the GDP revisions were the big headline, sending financials soaring today. According to revised figures, the American economy was more robust in the second quarter than previously reported, as growth of gross domestic product for the period was 3.3 per cent, ahead of previous estimates of 1.9 per cent.

But before you jump to celebrate, analysts caution that much of the GDP growth was driven by the weak dollar, which boosted exports by making America's goods and services cheaper for foreign buyers. In other words, these revised figures give false recovery hope:

The impact of more than $100 billion (£54.7 billion) worth of tax rebates, made by the US Government to its citizens, also helped to offset the impact of the US housing slump and high energy costs, analysts said.

The US will benefit less in the second half of the year from exports, as the economies of Europe and Japan slow and the dollar continues to gain value.

In addition, as many of the tax rebates have been spent, the economy will not continue to benefit from the fiscal stimulus in the second half.

Lou Crandall, chief economist at Wrightson Icap, said: "The revised GDP figure is certainly not a bad thing, but it is an imprecise estimate of the true health of the economy. It is still the case that GDP could turn negative in the second half."

Brian Fabbri, chief US economist at BNP Paribas, added: "The GDP figure may not say it but this country is still in trouble. Corporate profits have fallen for four consecutive quarters, companies have fired 60,000 workers a month in the past seven months and the outlook for the economy is pretty grim."

But for today, Wall Street wanted to party and forget about the second half of the year.

The other big story that caught my eye today was this article from the Wall Street Journal stating that pension funds are closely watching the on-going Fannie and Freddie saga:

Keith Brainard, a research director for the National Association of State Retirement Administrators, which represents the directors of retirement systems with combined assets of more than $2 trillion, said, "I'd be hard pressed to believe that the decline in share values for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are having a material impact on" pension funds.

While some of the unrealized losses may seem large, Mr. Brainard said, they represent a small percentage of a diversified pension fund portfolio of $153 billion or more.

There was "a lot of consternation" about the millions the San Diego County Employees Retirement Association lost when hedge fund Amaranth Advisors collapsed in 2006, but the fund's results for that fiscal year were "right in the middle of the pack with other public funds," he said. "I just think it's helpful to recognize the magnitude of these funds and their long investment horizons."

It wasn't long ago that some public pension funds announced that they were buying distressed mortgage products as a value play, Mr. Brainard said. "These funds are long-term investors who are out there looking for opportunities," he said.

Pension funds are indeed looking for opportunities in all sorts of markets, including the leveraged loan market:Leveraged loans, once a clubby arena dominated by banks and a few investment funds, exploded in the credit boom years thanks to a rise in mergers and acquisitions activity, and demand from structured products called collateralised loan obligations, which pool loans to sell on to investors.

But CLO issuance has dropped sharply and the level of takeovers has fallen. The lower demand and expectations of a rise in corporate defaults have driven loan valuations to below 90 cents on the dollar.

Ron Schmitz, chief investment officer of the Oregon Investment Council, which has invested nearly $4bn, 5 per cent of its portfolio, in vehicles dedicated to investing in loans in the past year, said: "Bank loans were a nice, stable, quiet market that didn't offer any particular bang for your buck. Now, for a variety of reasons, it does." Mr Schmitz expects returns in high-single digits even if defaults reach peaks.

A fund totaling close to $3bn that BlackRock launched last year to buy leveraged loans was taken up predominantly by pension funds inside and outside the US, said Barbara Novick, a vice-chairman at the firm.

I also read that one of the world's largest wealth funds, Norway's Government Pension Fund, is now increasing its target weight to equities from 40% to 60% and actively looking to invest in real estate.

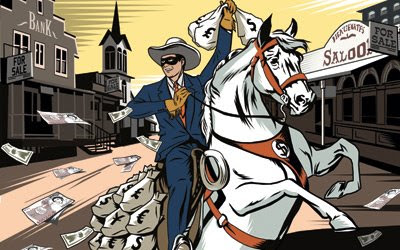

Interestingly, the Economist published an article today discussing whether private equity funds will ride to banks' rescue:

In most financial crises private equity is part of the problem. During a typical credit cycle it is among the first to use cheap financing to buy companies. Buy-out firms gradually become trigger-happy, overpaying and loading businesses with so much debt that some of them go bust. After the crash, the industry is in disgrace and skulks away to bind its wounds. Years later it returns, penitent, wiser—but hungry once again for cheap loans.In this financial crisis, however, private equity thinks it is part of the solution. Buy-out firms have struck lots of dodgy deals, certainly, but they are still rich and ambitious. And amid the financial wreckage of the credit collapse, private-equity partners think they have spotted a chance to make a lot of money by helping Western banks to repair their tattered balance sheets.

This strategy partly reflects private equity’s fund- raising before the credit crunch. Back then, pension and sovereign-wealth funds were not just sipping the buy-out Kool-Aid, they were swigging gallons of the stuff. As a result buy-out firms still have almost $450 billion of their cash to invest, according to Preqin, a research firm.The boom also fed buy-out firms’ aspirations. No longer are they content to act as Wall Street’s vigilantes, picking off the weak and the stray. Most now have high fixed costs, in the form of hundreds of employees. Their ageing founders long to diversify their firms and propel them into the top ranks of the financial establishment.

So private equity has the ambition to rescue ailing banks and it has the money. But does that make it a good idea?The article goes on to discuss the opportunities and risks of this strategy:

Yet there are risks, too. In buying LBO loans, the industry is doubling up its bet on a small pool of companies. Executives may believe in these businesses, but many of them are too indebted to cope with a downturn. Lately, the economy “has become a much higher concern” for loan traders, says Mr Taggert, which perhaps explains why loan prices have not recovered as the overhang of supply has shrunk. Most of the bank-financing packages stipulate that, if prices fall further, private-equity firms must post margin calls. And if the companies need to be recapitalised, it could lead to some toxic conflicts of interest—should debt investors be favoured over old equity investors? Can money raised for new buy-outs be used as equity to bail out old ones?

Even if LBO loans make money, they are more like a junk-food snack than a substitute for private equity’s staple diet of industrial companies. The supply of new loans is now limited, as many banks plan to keep the remaining exposures on their balance sheets. Most of the return from a typical LBO-loan deal comes from leverage. In the long run, clients are unlikely to pay high management fees for that.

The article ends off by stating:Before private equity takes the plunge, the rules may need to be tweaked. As early as next month, the Fed is expected to offer more guidance on the grey area of the ownership thresholds, probably relaxing its stance. Private-equity firms are also lobbying for the rules to loosen, so that they can form a consortium of buy-out firms without being deemed to have formed a “concert party” that has taken control. They also want permission from both the Fed and their clients to ring-fence the funds that invest in banks, so that their wider activities are safe from banking liabilities.

Will private-equity firms ride to the rescue of banks? Buy-out firms are unlikely saviours, but private equity’s $450 billion war chest is big enough to fill Western banks’ capital shortfall. There are few other sources of ready capital. Sovereign-wealth funds have been badly burnt; banks cannot easily raise equity in public markets; and the atrophy in many of the biggest lenders leaves them in a poor state to buy the weakest.

So regulators in America and elsewhere may feel obliged to ease their ownership restrictions. Until this year private equity had stuck to form, recklessly buying industrial firms at the top of the credit cycle. But the industry’s next guise could be less familiar—and more welcome. Private equity, saviour of Western banking. Who would have thought it?

My own thoughts are that PE funds, replete with cash from global pension and sovereign wealth funds, see an opportunity to lobby governments around the world to loosen regulations so they can muscle in on the banking industry and print money at will. If they fail, no worries, the Fed will bail them out.Of course, let's not forget, PE funds will charge egregious fees for this "active management" and pension fund managers will continue to praise their allocations into alternative investments, reaping large bonuses as they claim they're adding "significant alpha" by beating bogus benchmarks.

It sure looks like one big club to me and they are all placing their bets on a magical recovery that is unlikely to materialize. By the way, guess who will end up footing the bill if things go awry?

Welcome to the reckless new world of Moral Hazard!!!

Comments

Post a Comment