Will Stocks Crash After Entering the Valuation Twilight Zone?

Nineteenth century French writer Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr didn’t have stock market history in mind when he said, “the more things change, the more they stay the same,” but he might as well have.

Sometime in the future, the markets will respond in exactly the same way as they have in the past. But you must know the market’s history if you’re to succeed on the long road ahead. Sadly, most investors have no such knowledge and without it, they are treading on thin ice.

In 2017, I wrote an article about the long-term history of the stock market. I have updated the data from the end of 2016 to the present. In my opinion, we have entered the twilight zone when it comes to valuations — the parallels to the late 1990s have never been so stark. Frankly, I think we are on the precipice of history repeating itself.

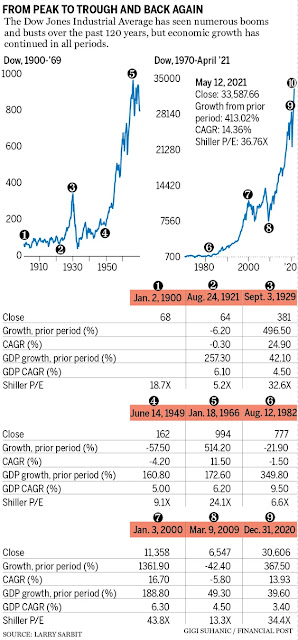

The accompanying table shows 120 years of U.S. stock market history from the beginning of the last century until today. I’ve noted the peaks and troughs of the Dow Jones Industrial Average over that period. I’ve also included the growth of GDP and the Shiller P/E ratio, a cyclical ratio that takes into account 10 years of earnings.

At the beginning of the 20th century, stocks were expensive with the Dow at 68 and the P/E at almost 19 times earnings. Twenty-one years later, the market was unchanged, but stock valuations as measured by the P/E were at just 5.2 times earnings — those are bargain prices. No one wanted to own stocks because, why would you want to put money in the market that had delivered no capital gains returns over 21 years? Warren Buffett labelled this, “rear-view mirror investing.”From the bottom of the market, we witnessed the “Roaring Twenties” with the stock market going on a tear — stocks were up nearly 500 per cent and the P/E was almost 33X — until 1929.

This market top ushered in the Great Depression with the market bottoming out 20 years later in 1949, down a massive 57.5 per cent from its highs. Valuations were at 9.1 times earnings, a fraction of the 1929 highs. Again, we can assume investors had no interest in owning shares of businesses.

At this point, the market again took off, advancing more than 500 per cent with stocks priced at 24 times in 1966, a full 17 years later. Again, another drop in the market to the bottom in 1982 when stocks were trading at a very low level of 6.6 times earnings. Then, the following mega-market lasts an incredible 18 years, finally topping out in 2000 with valuations reaching an unprecedented 44X and the bursting of the dot-com bubble. And finally, stock prices bottomed out in early 2009 and once again you could not get people to buy stocks.

At the time, I wrote about my efforts to get advisers and their clients to load up at those cheap prices. The universal question I received: “Does your fund have any U.S. stocks in it? Because if it does, we have no interest.” This was an almost unanimous reply.

(These are wonderful indicators. History shows that when everybody agrees about the stock market, something very different or opposite is about to happen.)

From that bottom, stocks have gone on another long bull run, appreciating more than 400 per cent to current market levels. And valuations have gone from 13 times in ’09 to 37 times today, not far from the high-water mark set in 2000.

Now turn to the GDP columns. They show the economy going in just one direction through every period — up. Pick any time period, especially the periods of stock market decline and you will see the economy advancing even in the face of massive declines in the stock market. Why is there such a disconnect between the stock market and the underlying economy? Shouldn’t stock prices rationally reflect the growth in the economy?

Buffett had the answer in his seminal article in Fortune magazine in 2001. Investors behave in human — that is, emotional — ways. They get very excited in bull markets and make the recurring mistake of investing with their eyes locked on the rear-view mirror. Valuations be damned.

“When they look in the rear-view mirror and see a lot of money having been made in the last few years, they plow in and push and push and push up prices,” Buffett wrote. “And when they look in the rear-view mirror and they see no money having been made, they say this is a lousy place to be.”

Since I last wrote about this at the end of 2016, the Dow has exploded, rising by more than 70 per cent. Valuations have gone from 29 times to 37 times. Investors once again are looking backward down the investing highway. Staring only in that direction can lead to serious financial accidents. More money has nevertheless continued to pour into the stock market and into riskier asset classes such as cryptocurrencies.

And as the past 120 years have shown us, we have a good chance of a significant decline in stock prices. Both the business environments and investment participants have changed a great deal over the years. But one thing has remained the same — investors’ emotions and irrational behaviour. On these, you can be absolutely sure.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

So, caveat emptor.

A great article written by a value manager who is warning investors that valuations matter and stocks are bloody expensive now.

With all due respect, however, you could have said the same thing a year ago when I wrote about how central banks all over the world led by the Fed have unleashed the mother of all liquidity orgies, probably the last one we'll see in a very long time.

I knew things were getting wacky but had no idea how wacky as quant funds pumped concept stocks up to the moon.

Case in point, look at shares of Nio (NIO), Plug Power (PLUG) and Snowflake (SNOW), all are up big today but they have gotten destroyed since the beginning of the year (after an explosive run-up last year):

What has led to such a violent sell-off since the start of the year? Rising rates. When rates are at record lows, you can invest in hyper growth stocks making no money but as soon as they started to rise, investors (more like quant hedge funds that pumped them up) pulled the plug (no pun intended).

Nowhere is this more prevalent than the hyper growth stocks which rallied like crazy last year as the pandemic hit and rates fell to a record low.

Just look at Cathie Wood's Ark Innovation ETF (ARKK), it's up more than the Nasdaq today but it's gotten clobbered since peaking earlier this year:

I actually wrote about the unARKing of the market a couple of weeks before the ARKK ETF peaked and I'm afraid to say, I don't think we have seen the worst of it yet.

In my opinion, there's still so much hype in these markets fueled by insane liquidity and the whole FOMO, TINA, and WSB/ YOLOers of the world uniting which are nothing more than large, sophisticated unscrupulous hedge funds pumping and dumping stocks at will as they spread nonsense on social media and online stock chat sites.

In short, the level of criminality out there is unprecedented but regulators are staying mum because clamping down on all this nonsense would mean deflating the bubble and that's a scarier option.

Meanwhile, central banks led by the Fed are cornered, they're increasingly meddling in markets, petrified of what happens when everything crashes, but in doing so, they're creating severe economic dislocations, exacerbating inequality and quite frankly, sowing the seeds of the next major deflationary crisis which I believe will make the 1974-75 bear market look like a walk in the park.

And now a new study brings a fresh warning for retirees hoping to rely on the so-called “4% rule” to make their money last until they die:

Those expecting to retire soon may face a “worst-case scenario” as a result of elevated stock prices and record low bond yields, warn Jack De Jong, finance professor at Nova Southeastern university, and John Robinson, a financial planner in Honolulu (the pair are co-founders of a financial planning business, Nest Egg Guru). Many need to slash their spending as a result.

And the pair calculate that many of those who retired 20 years ago, at the lowest peak, and relied on the 4% rule may already be in trouble.

The so-called 4% rule was coined by financial planner William Bengen in 1994. Using historical data, he estimated that a new retiree should be able to make their money last for their remaining years if they followed a simple two-step process.

First, in the initial year of retirement, spend no more than 4% of your portfolio’s value. And second, in all subsequent years, increase that spending only in line with inflation.

For those who retired around 2000, the “4% safe withdrawal rate will likely fail well before 30 years for most asset allocations,” De Jong and Robinson calculate. Those retirees were devastated by the “nightmarish. lost decade” for stocks from 1999 to 2009, which included two devastating crashes. “Much of the conventional planning wisdom, including the vaunted “4% rule,” failed investors during this period.”

And even though U.S. stocks boomed after 2009, it was too late for many retirees, they report. Anyone who had spent 4% of their portfolio in 2000 raising it in line with inflation each year afterward, had spent too much of their savings by 2009 for them to recover.

This is what’s known among financial planners as “sequence risk.”

There are some caveats here, which are in the fine print. The pair assumed retirees increased their spending 3% a year over the past 20 years instead of simply in line with the official CPI. Also, more significantly, they assumed retirees were also paying 1% a year in fees, taxes and other costs. In other words, the 4% rule was more of a 5% rule.

I ran my own model using a spreadsheet, the official CPI, and the returns from a rough-and-ready benchmark of a balanced portfolio, the Vanguard Balanced Index Fund (VBINX), which is 60% U.S. stocks and 40% U.S. bonds. In my calculations, those who retired in 2000 and applied the 4% rule, raising spending no more than in line with the CPI, are still OK today, 20 years on. They’ve actually got about 88% of their initial portfolio left. But this assumes no taxes, fees or other costs. If you’re paying 1% of your portfolio value a year, you’ve been almost wiped out by now. Yes, costs — including fees — can make that much difference.

What’s ominous for today’s likely retirees is that current math looks even worse than it did in 1999, at the peak of the last stock market mania.

That’s because retirees typically hold a portfolio of stocks and bonds. And while stocks are not quite as expensive today as they were in 1999, bonds are much more so.

Back then 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds paid interest rates that were about 6%, or twice the rate of inflation. So people who put their money in bonds were getting well paid.

Today the same bonds pay interest rates of just 1.6%–or less than the rate of inflation.

The lost decade after 1999 “does not represent a ‘worst-case’ scenario because the bear market in stocks was accompanied by an extension in the decadeslong bull market in bonds,” write DeJong and Robinson. “A worst-case scenario would be one in which the lost decade for stocks began and lasted over a period when interest rates were at historic lows and either stayed low or rose in conjunction with high inflation.” And that, they add, may be what retirees face now.

In the summer of 2000, when the stock market was just around its bull market peak, I had lunch near London’s Covent Garden with my late friend Peter Bennett. He simultaneously called the Nasdaq “the most obvious short of my entire life,” and inflation-protected Treasury bonds known as TIPS, which then promised guaranteed interest rates of inflation plus 3% a year, “an absolute gimme.”

To conventional wisdom at the time he sounded crazy on both fronts. But his clients soon had cause to thank him.

What this article highlights is that people retiring now face the very real prospect of diminishing stock and bond returns over the next decade and they run the real risk of outliving their retirement savings.

Of course, inflationistas are pounding the table this week, they think massive inflation is on the horizon and rates going to back up significantly.

I say "bullocks" and keep warning my readers that deflation will be the endgame from all this nonsense.

Again, let me give you two scenarios:

- We get an unanticipated inflation shock (doubt it), rates back up, the Fed is forced to hike rates, stocks and the economy crash and we enter a long period of deflation.

- Or stocks, cryptocurrencies, commodities and other risk assets (like high yield bonds) keep inflating into bubble territory, more leveraged funds take increasingly dumb risks like Archegos to leverage their fund using total return swaps, we get a full-blown financial crisis and again, a long period of deflation as the financial crisis leads to another economic depression.

No worries, the Fed and other central banks stand ready for any scenario, they know what they're doing.

But I am worried, more worried than ever before that this market will crater so fast, it will leave destruction in its wake.

And all sectors will get hit if this happens, not just the hyper growth stocks but even cyclical stocks (financials, industrials, energy and materials) that have been all the rage lately as COVID restrictions have been lifted in the US.

Don't worry, stocks aren't crashing anytime soon, but if you're really paying attention to how all stocks are trading, including cyclical shares, you'll see huge volatility which tells me investors and traders are nervous.

Below, Stan Druckenmiller, CEO of Duquesne Family Office, joined "Squawk Box" earlier this week to discuss why he believes the Fed shouldn't be in emergency mode and warns that the distortion of long-term interest rates is risky for the economy and for the Fed itself.

This is a phenomenal interview with one of the greatest money managers of all time, take the time to listen to him. I don't agree with his short USD call but he provides so many great insights here.

Comments

Post a Comment