Is Private Debt The Next Subprime Debt Crisis?

Earlier this week, I spoke with Deborah Orida, President and CEO of PSP Investments on their new partnership with AIMCo to explore and invest in private loans.

I told Deb to read my Outlook 2023

to understand why I am very bearish and foresee major dislocations across public and

private markets this year, including private debt and credit in general,

"so those double-digit returns you were getting since inception of the program at PSP are

going to be much more difficult to get in the next 2-3 years."

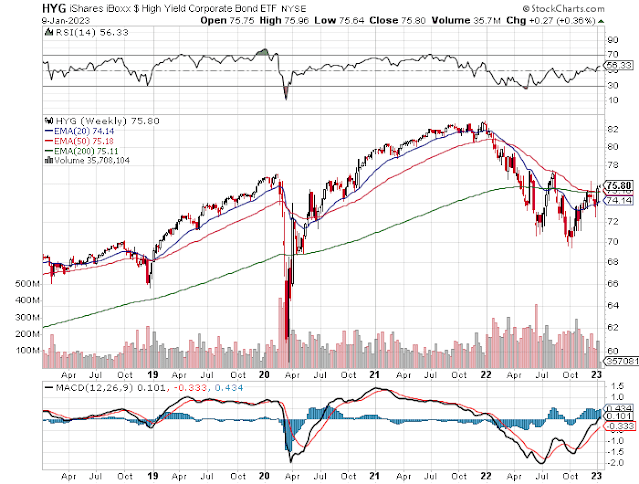

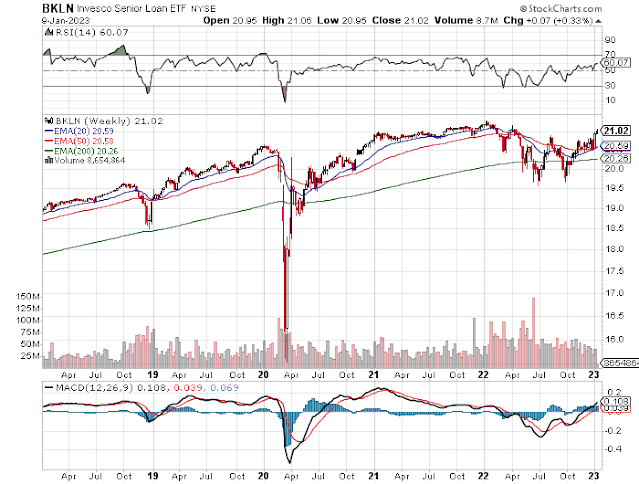

I told her I expect more pain in high yield credit (HYG) and the leveraged loan market (BKLN) and this will spill over into private debt:

Deb replied:

In terms of the market, we have a highly diversified portfolio that has good exposure to some things that are well-positioned in this market like credit, like natural resources.

Our credit book as you know, the vast majority is floating rate so our existing portfolio is in good shape and going forward what we are seeing is only the best recession-proof businesses are getting financed and they're now getting financed at higher rates and on better terms.That's why we think the private credit market is really exciting and our sophisticated platform will continue to get a lot of calls and this partnership with AIMCo positions us well to be able to pick and choose to play across that credit opportunity set.

She's right floating rates will help them in a higher inflation/ higher rate environment. I asked her about the link between private debt and private equity over the last few years and how sponsored backed deals were critical to PE deals:

I would say over the last couple of years, we increased our collaboration between our private debt and private equity teams. And that will continue under the new leadership with Oliver and Simon.

But they're still addressing independent markets. So, we work together where it makes sense but they are two separate groups that existed under David and now we are elevating Oliver, and he will continue as he did before running global credit, and we are elevating Simon who will continue to run global private equity.

At the end of that comment which has garnered over 17,000 views on LinkedIn, I stated I had a conversation with a private debt expert who raised a lot of interesting points on the embedded risks of unitranche loans that many investors are unaware of:

He said this about unitranche loans:

Within the past several years, this has been a popular mode of financing for the sponsored-backed group. They are a single loan that encompasses both senior and junior into one product.

Typically you would have a senior loan -- let's say a bank or private credit institutional fund would provide financing for -- whereas the junior loans which would be the more aggressive opportunistic loans.

With unitranche loans, you now have a product that is averaging this into one product, so what we end up getting is a senior loans with inherent junior credit risk embedded in it.

I asked this person if this is similar to the subprime credit crisis when they were packaging all these subprime mortgages together and then the credit rating agencies would slap a AAA credit risk rating on them so investment banks can sell them to institutional clients hungry for yield:

Exactly. And this is one of the issues I see permeating the industry. We see a lot of funds marketing themselves as senior type funds but when you look at the nitty-gritty details and their underlying exposures, there's a lot of untitranche product in there.

So then the question becomes are they properly accounting for that junior exposure in their OMs (offering memorandums) when they're talking to potential investors? So I think we are going to start to see a wave of defaults hitting a lot of funds or hitting a lot of asset managers that thought they were in senior only type structures.

I asked him who oversees these structures and whether they are truly investing in what they claim:

So, let's look at the two key parties. You have the underwriter originator which is the portfolio manager and then you have the investor. So the originator and portfolio manager are aware of their exposure but my question for the broader audience is if the investors are aware that there is unitranche exposure that has inherit junior credit risk or is that portfolio manager calling that unitranche in senior only loans?Stunned, I naturally asked: "Are you telling me there's no third party validation of these unitranche structures and whether they have junior credit risk exposure?!?!?":

Exactly Leo and that is why I fear a lot of investors whether it be your portfolio manager or mutual fund manager buying private credit exposure or structures, are they aware of the true inherent risk of a unitranche loan?

My answer would be only sophisticated private credit managers like a CPP Investments, like myself who understands what a unitranche is would be able to look at that and say wait a second, what is being classified as a senior product actually has like you said 10, 15 20% or more of equivalent junior credit risk but because untitranche loan packages first lien and second lien into one product, most asset managers who fell into this kind of glossed over that point.

He told me investors should always ask about what exactly is in the unitranche loan (what percentage is first lien, second lien, equity) and whether that changes the credit risk profile:

Again, this has been glossed over in many marketing materials. Remember, it's the junior guys that will fail first. The tide will turn. I think we can all say with certainty, defaults will start increasing. So any holder of second lien paper are going to feel the hit first but if you're holding unitranche, you too will be exposed to second lien default risk that you didn't know was embedded in your product.This is why it's important to have a sophisticated investor like CPP Investments or PSP Investments as a partner because they have an experienced team that is able to dig into these unitranche loans to see what exactly is their risk profile in terms of second lien loans.

I told this person that what worries me a lot, and I alluded to this in my Outlook 2023, is there is a lot more risky debt across public and private markets all over the world that isn't accounted for properly and this could lead to a liquidity crisis unlike anything we have seen yet.

This is what Mohamed El-Erian and others are warning of so pay attention to this unitranche story as we head into a historic and painful earnings recession.

This is why IMCO and others are smart to invest with Antares Capital owned by CPP Investments and why AIMCo is smart to partner up with PSP Investments to explore and invest in private loans.

But let me be clear, we are headed into a very difficult and turbulent period, there might be great opportunities in private credit but there are huge risks too.

That goes for everyone, no matter how sophisticated they are. You can forget about double-digit returns in this space over the next couple of years.

Still, this agreement between PSP and AIMCo just like IMCO's agreement to invest in Antares is a win-win over the long term.

I also think with Marlene Puffer and David Scudellari joining AIMCo, Evan Siddall is gaining two experienced veterans on his senior management team to help him lead that organization.

As an aside, Evan, David and Deb all worked together at Goldman Sachs a while ago and they're all top-notch professionals.

Update: I asked the credit expert if this Horizons Active Floating Rate Senior Loan ETF (HSL.TO) which seeks to provide unitholders with a high level of current income by investing primarily in a diversified portfolio of U.S. senior secured floating rate loans, generally rated below investment grade and debt securities, is worth tracking.

He replied: "Yes, I know it well and would be worth tracking for a private credit benchmark equivalent and perhaps acquiring some after the default cycle (which nobody can predict)."

Now, earlier today after the US CPI report came in as expected, I had a discussion with my favorite currency trader in Toronto who basically agreed with me and Francois Trahan that wage inflation will pick up in the second half of the year as employment falters, forcing the Fed to hike again after a long pause:

Nightmare scenario: Headline inflation keeps cooling in first half of year. The Fed hikes by 50 bps at each initial meetings then pauses for 6 months. In meantime, employment starts weakening BUT wage inflation starts picking up forcing the Fed to hike rates again later this year

— Leo Kolivakis (@PensionPulse) January 12, 2023

He told me: "I've been saying it since last year, wage inflation will pick up this year and if the Fed starts hiking again after a long pause, it's going to kill the market."

He added: "But what I really want to talk to you about is this unitranche debt mixing secured with unsecured debt you wrote about a couple of days ago, it sounds like the subprime debt crisis all over again."

I replied: "Yes, that's exactly what I told this credit specialist who spoke to me."

He was amazed that they're "co-mingling secured with unsecured debt" packaging it as senior loans and no media outfit is talking about this but rather about the boom in unitranchedebt.

He added: "It's private so they don't have rating agencies rating this stuff, nobody really knows what proportion of the trillions in unitranche debt is secured (senior) and unsecured (junior)."

I replied:

Well, I'm sure the data exists from Refinity but it's kind of scary when you think about it and as the credit specialist explained to me, only very qualified senior credit analysts can dig through a portfolio to understand what percentage of unitranche debt is first lien and second lien. Most investors who came late to the asset class don't have a clue of the underlying credit risks.

My friend said: "Same story, every time, do you remember 2008 and the ABCP crisis that almost brought down the Caisse?"

I replied:

Do I ever. Right before I got fired at PSP in October 2006 for 'being too negative' after I did research on CDO-squared and cubed and told them the issuance was off the chart and downright scary, I had lunch in March of that year with Henri-Paul Rousseau, the former CEO of CDPQ, at Molivos restaurant. Gordon Fyfe knew about it because I told him (after I left CDPQ to join PSP,I sent an email to Rousseau to meet him and he came back to me late but we did have lunch).

Anyway, I remember Rousseau was a gentleman, very smart and polished, and he had a voracious appetite (he's a big guy and Molivos had amazing Greek food). I also remember asking him if he's worried about risks in the Caisse's portfolio and he told me flat out: "Leo, one thing I can assure you, the Caisse has the best risk management in the pension industry."

Well, the rest is history. The ABCP scandal cost the Caisse billions that year when they lost $40 billion and Rousseau was out and replaced by Sabia.

I added:

I kind of felt bad for Rousseau because it tarnished his image and I don't think he fully understood the risks that Luc Verville was taking in money markets devouring ABCP to easily beat his T-bill benchmark or the huge risks that Christian Pestre was taking in his exotic and illiquid long swap strategy using the balance sheet of the Caisse.

[Worse still, the Caisse was a minority owner of Coventree, the firm at the center of the ABCP scandal, so talk about conflicts of interest and double-dipping! I remember the day in the summer of 2007 when I was in Toronto staying at the Fairmount hotel, saw a red-faced Rousseau mad because they had a meeting with the Bank of Canada and other players to try to get the Bank to buy this paper off their books and then BoC Governor David Dodge rightly said "NO!".]

But Rousseau was easily influenced and made some terrible decisions. In fact, he gave Pestre free rein to do whatever he wanted back then and told everybody "don't bother him, he's brilliant and knows what he's doing."

It's too bad because till this day I think very highly of Henri-Paul Rousseau, he had political aspirations and I think he would have made a great Premier of Quebec, even better than Legault.

I went on:

The same thing was going on at PSP but to a lesser scale on ABCP. Still, we had exposure, Gordon Fyfe never forgave the National Bank for selling us that crap.

In the meantime, I was going through hell because they kept bouncing me back and forth from one department to another knowing I have multiple sclerosis and was very stressed and tired.

At that point, Gordon asked me to figure out where I can add value so I started doing research on the issuance of CDO-squared and CDO-cubed, and looking at the insane issuance, I knew it was only a matter of time before the US housing market blew up and there would be a massive credit crisis.

I was also freaking out because at the time Jean-Martin Aussant (who later became a well known politician) was selling credit default swaps using the balance sheet of PSP and was telling everyone it would take a 20-sigma event for his portfolio to lose money (he wan’t the one buying ABCP at PSP).

My friend asked: "So, what happened?"

I replied:

Well, what happened is I asked Gordon to have breakfast in September 2006 and I hate waking up early to have breakfast with anyone but he doesn't do lunches (goes to the gym).

Anyway, at that breakfast, I showed Gordon the research charts I was working on and told him I was petrified of the credit risks Aussant and his team were taking in the internal credit portfolio (he didn’t act alone). He told me: "Leo, you were my first investment hire at PSP because I know you're very smart but a few people in my senior management told me you're too negative and not a team player. If you're not careful, you risk losing it all but right now you have nothing to worry about."

I knew I was toast. Turnover rate back then was insane and a few weeks later, Pierre Malo (my boss back then) called Mihail Garchev and I into his office to tell us he can't guarantee we will have a job. Soon after, I was fired from PSP even though I had stellar performance records.

Given my health battles, I didn't take it well but like Nietzche said a long time ago: "Out of life's school of war, what doesn't destroy me makes me stronger"

I've also maintained a relationship with Gordon over the years (phone calls and emails once in a while) and it might sound weird to many people reading this but I still think very highly of him even if he too made huge blunders back then trusting people who he shouldn't have trusted (to be truthful, we all made our share of mistakes).

My friend said this:

It's always the same story at these large pension funds, everyone is worried about career risk and they're all looking to game their benchmark using any way they can.

Look at private debt. It mushroomed over the last ten years as rates hit ultra lows and private equity was booming.

So the pension funds invested billions in private equity and these PE funds returned the favor by taking on more unsecured debt which they package with secured debt and have the pensions finance their operations through unitranche debt from their private debt teams.

The pension funds can claim they're making double-digit gains and adding alpha and everyone is happy making millions in bonuses. It's a win-win-win-win for PE funds, senior pension fund managers, their Board and their contributors and beneficiaries.

I interjected: "Yeah, until something blows up."

My friend: "Ah, yes, but by then these senior pension executives are all long gone, retired, and couldn't care less as long as they made millions while at these top jobs. Can't blame them, everyone is looking to maximize their revenues."

I asked: "I wonder what the Board of Directors at these large pension funds know about the embedded risks in private debt."

My friend cynically replied: "They probably don't know anything because they ask their risk managers and senior executives to give them some risk report and they take it at face value without having it independently verified by an expert third party."

I said: "Well I don't think it's that bad."

My friend: "Leo, I'm telling you it's that bad. As you said, ask any Board member at these large pensions what percentage of their private debt is second-lien unsecured debt and I doubt they know and if they do, I doubt it has been verified by independent experts who can vouch for it."

I replied:

And I'm afraid therein lies the truth, while private debt has become a very popular asset class and in intrinsically linked to private equity which sponsors this unitranche debt, we do not have reliable industry data which tells us how much of total unitranche debt issues over the last five years is made up of second lien debt.

My friend: "They should make it illegal to co-mingle first-lien with second-lien loans and market it as senior only."

I replied: "It's too late and I'm really afraid when this private debt boom blows up, it will wreak havoc across the global financial system much like subprime debt did back in 2008 when it blew up."

Let me be very clear to all my readers, we simply don't know where the next credit crisis will come from but as I'm learning more about private debt, I'm realizing that all this "floating rate" inflation hedging is a bit of chimera, hiding the real embedded risks in unitranche debt.

If anyone can find me a bar charts of total unitranche debt issued over the last ten years and then also find how much of that is first-lien and second lien loans, please send it to me asap and I will embed it below right here.

[Lots of free information on The Lead Left and see the Economist article: More borrowers turn to private markets for credit]

As the Fed tightens and rates keep climbing, you have to wonder however whether there will come a time when one of these Johnny-come-lately private debt funds blows up and credit risk spreads all over the world.

I am also openly wondering why long dated Treasuries are rallying when the Fed is still in tightening mode during a slowdown. Is the bond market sniffing out the next credit crisis which is already upon us?

The bond market is wrong as the Fed is still in tightening mode EXCEPT if it is sniffing out the next major credit crisis...STAY TUNED!

— Leo Kolivakis (@PensionPulse) January 13, 2023

Also why did Libor eclipse the peak it reached in wake of Lehman’s collapse today:

One of the world’s most important short-term lending benchmarks has climbed back to a level last seen before the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008.

The three-month London interbank offered rate for dollars climbed 1.5 basis points on Thursday to 4.82971%, exceeding the peak of 4.81875% it reached in October 2008 when credit markets were in disarray following the shock collapse of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. The last time it was higher was in 2007.

The spread of Libor over overnight index swaps — a barometer of funding pressure — was at 16.3 basis points on Thursday versus 17 basis points the prior session.

Much of the recent surge in Libor, which is set to be phased out on June 30, has been driven by expectations for Federal Reserve policy tightening. The benchmark is moving in sympathy with many other short-term rates, but there are other elements that feed into the daily setting, including the backdrop for commercial paper transactions and broader credit conditions.

“It is supposed to reflect bank funding costs,” said Priya Misra, head of global rates strategy at TD Securities. “As reserves are falling, banks are paying up for funding.”

The minutes of the December Fed meeting published this month noted that banks continued to increase their use of wholesale funding, and survey information suggested lenders expected to move deposit rates “modestly” higher in the coming months. Misra said the higher deposit rates are also consistent with higher Libor.

Most Libors around the world came to an end at the close of 2021, but regulators decided to extend the life of some dollar-denominated reference rates for an additional 18 months. A Fed-backed committee designated the Secured Overnight Financing Rate, known as SOFR, as the successor to US dollar-denominated Libor.

Now, the bulk of private debt is in the shadow banking system which includes hedge funds, private equity finds and pension funds, so it shouldn't put pressure on banks' funding cost but you have to wonder if banks are also worried about a major credit event and counterparty risk.

Having said this, while banks don't carry private debt on their books they do originate and package this debt for clients (this is an indisputable fact).

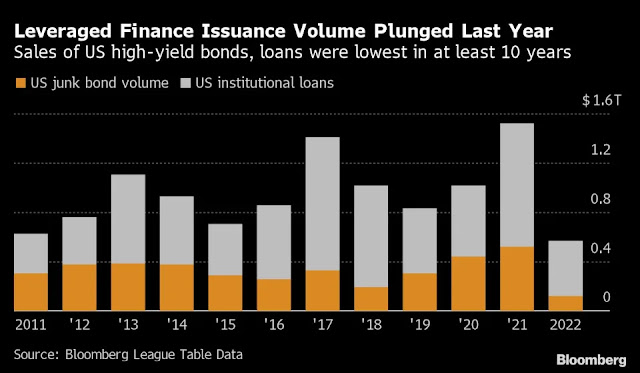

Also, banks are exposed to the a slowdown in private equity as witnessed by the huge decline in the leveraged finance boom that fueled their profit last year:

One of the most lucrative money-making machines in the world of finance is all clogged up, threatening a year of pain for Wall Street banks and private-equity barons as a decade-long deal boom goes bust.After driving a flurry of mega buyouts that contributed to a $1 trillion profit haul in the good times, some of the world’s largest banks have been forced to take big writedowns on debt-fueled mergers and acquisitions underwritten late in the cheap-money era. Elon Musk’s chaotic takeover of Twitter Inc. is proving especially painful, saddling a Morgan Stanley-led cohort with around $4 billion in estimated paper losses, according to industry experts and Bloomberg calculations.

The easy days aren’t coming back anytime soon for the fee-rich business of leveraged lending as a much-anticipated recession looms. Cue oncoming cuts to bonuses and jobs across the investment-banking industry as firms from Goldman Sachs Group Inc. to Credit Suisse Group AG contend with a slump in revenue.

Few have dodged the fallout. But Bank of America Corp., Barclays Plc and Morgan Stanley are among the most exposed to around $40 billion of risky loans and bonds still stuck on bank balance sheets — whose value has fallen dramatically as institutional buyers vanish.

“The dislocation is more pronounced and longer lasting than anything since the Great Financial Crisis,” said Richard Zogheb, global head of debt capital markets at Citigroup Inc. “Investors have no appetite for cyclical businesses."

The most sophisticated players, paid to know when the music stops, were doling out risky corporate loans at what now looks like ludicrously generous terms as recently as last April — effectively betting that the easy-money days would live on even as inflation raged. Now the Federal Reserve’s resolve to tighten monetary policy at the fastest pace in the modern era has left them blindsided, cooling the M&A boom that’s enriched a generation of bankers and buyout executives over the past decade.Read More: Wall Street's Top Stars Got Blindsided by 2022 Market CollapseIn a sign of how risky financing has all but dried up, a big private-equity firm was recently told by one of Wall Street’s biggest lenders that a $5 billion check for an LBO — no biggie in the halcyon days — would now be out of the question. It's a similar story from New York to London. As the credit market slumps, bankers are either unwilling or unable to fire up the high-risk-high-reward business of leveraged acquisitions.

Representatives for Bank of America, Barclays and Morgan Stanley declined to comment.“There’s no magic bullet,” said Grant Moyer, international head of leveraged finance at MUFG. “There's $40 billion out there. Certain deals will get cleared. But not every deal will clear the balance sheet in the first quarter or the second quarter. It's going to be a while.”The freewheeling excesses of the low-rate years are no more. In that era, leverage soared to the highest since the global financial crisis, investor protections were stripped away, and ballooning debt burdens were masked by controversial accounting tricks to corporate earnings that downplayed leverage. Now as interest rates jump and investors flee risky assets, financiers are having to adapt their playbook.

Bankers can take some comfort from the fact that projected losses on both sides of the Atlantic are still modest compared with the 2008 bust when financial institutions were stuck with more than $200 billion of this so-called hung debt. And the fixed-income market may yet thaw, allowing bankers to flog off more of their loans and bonds without realizing massive writedowns. But that’s an optimistic take. A more likely prospect: An industry-wide reckoning as leveraged-finance desks grapple with what some sober-minded bankers in the City of London call their “lists of pain” — underwater deals that include Apollo Global Management Inc.’s acquisitions of auto-parts maker Tenneco Inc. and telecom provider Brightspeed. When Wall Street lenders fully underwrite a financing, they’re on the hook to provide the cash at agreed terms. When times are good, that’s not usually a problem since banks can sell the debt to institutional investors who are hungry for higher-yielding assets. Those commitments have helped grease the M&A machine since it reassures target companies that transactions won’t fall through in the event the buyer finds it difficult to raise the capital. In return, bankers earn handsome fees, often ranging between 2% and 3.5% of the value of the entire financing, and the most senior can pocket multi-million-dollar bonuses along the way.

But those days are over for now — a casualty of Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s mission to tighten financial conditions, curtailing speculative lending activities in its wake. While there have been a handful of M&A deals in recent months, these transactions have typically been underwritten on less-risky terms that pay modest fees as banks focus on shifting the around $40 billion of debt they’ve been stuck with — a burden that may get bigger. If and when regulators green light Standard General’s purchase of media company Tegna Inc., for example, bankers risk being saddled with billions of dollars in debt that they agreed to provide for the deal before risk premiums spiked.

“We live in the constant knowledge that the leveraged financed market is cyclical, that markets turn, that acceptability of leverage changes over time and market appreciation of risk is constantly shifting,” said Daniel Rudnicki Schlumberger, head of EMEA leveraged finance at JPMorgan Chase & Co.The debt hangover at some of the world’s most systemically important lenders is tying up their limited capital to power new LBOs, leaving the pipeline for deals at its weakest in years with soft echoes of the global financial crisis.

As a result, leveraged-finance bankers are at risk of receiving the most meager bonuses in possibly a decade, and some banks will likely only reward their stars. Industry-wide layoffs could be steeper than for peers in other parts of the investment-banking business, according to people familiar with the matter, who aren’t authorized to speak publicly.“Last year was a tough one for leveraged finance,” said Alison Williams, senior analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. “We expect 2023 to face the same pressures, if not more acute.”The $12.5 billion of leveraged loans and bonds that backed Musk’s buyout of Twitter is by far the biggest burden weighing on bank balance sheets for any single deal. A group of seven lenders agreed to provide the cash in April, when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and rising interest rates were already rocking global markets. By November, just a couple of weeks after the deal had closed, confidence in the company had eroded so rapidly that some funds were offering to buy the loans for as little as 60 cents on the dollar — a price typically reserved for companies deemed in financial distress. That was before Musk said in his first address to the social media firm’s employees that bankruptcy was a possibility if it doesn’t start generating more cash.

Bankers indicated that those offers were too low, and that they weren't willing to sell the debt below a threshold of 70 cents on the dollar. Based on these types of levels — and even steeper discounts for the unsecured piece of the financing — estimated paper losses are around $4 billion, according to the industry experts and Bloomberg calculations. Morgan Stanley, which wrote the biggest check, would absorb about $1 billion, based on those same estimates and calculations.

Twitter is difficult to value but lenders will have to account for the burden somehow even if the exposure isn’t singled out. And if Wall Street has any hope of selling the debt at less onerous discounts, they’d likely have to show Musk is making good on his mission to bolster ad revenues and earnings.“Banks will err on the side of being conservative in their disclosures,” said veteran banking analyst Mike Mayo at Wells Fargo & Co. He believes that prior to the fourth-quarter earnings just about to kick off, that “banks have likely taken half of the potential losses in drip and drabs so far on Twitter.”Representatives for the seven Twitter lenders declined to comment. A spokesperson for the social-media firm didn’t respond to requests for comment.

With debt commitments hard to come by, the long-standing ties between Wall Street and private equity shops, like KKR & Co. and Blackstone Inc., are at risk of weakening. Banks have limited firepower and those who say they are open for business are still offering terms that sponsors see as unattractive. As long as demand for leveraged loans and junk bonds stays weak, investment bankers will lose out on lucrative underwriting fees.

“We're in a period of stagnation now where there hasn't been a lot of new net issuance in 2022 and there probably is not going to be much in 2023,” said Schlumberger at JPMorgan. “It doesn't mean there won't be activity, we are expecting a pick-up, but it will be very much refinancing-driven.”

Given the higher cost of debt, buyout barons are finding it challenging to get new deals done even as asset valuations have fallen. Among the handful that have cropped up, leverage is either sharply lower, or has disappeared entirely at the get-go — think leveraged buyouts without the leverage. Equity checks have gotten fatter, while some buyout attempts have fallen through. That points to potentially reduced returns for private-equity firms if debt remains elusive.“The hung debt will be an impediment to dealflow in the first half, but offsets include opportunistic refinancing, loan-to-bond supply and base effects since we were down 80% last year,” said Matthew Mish, head of credit strategy at UBS Group AG.

Banks have carved out more protection for themselves on some recent financing packages pitched to buyout firms, by requiring more flexibility to change the price at which debt can be sold within a pre-agreed range. The lowest price of that band, a level at which banks would still be able to avoid losses, has dropped to mid-80 to 90 cents on the dollar, according to people familiar with the matter, from as high as 97 cents before the market turmoil. In Europe, that floor has fallen to extremes in the low 80s, the people added, underscoring just how risk-averse banks have become. Private equity sponsors have usually been walking away from these offers.Even giants like Blackstone are struggling to clinch debt capital like the good old days. For its purchase of a unit of Emerson Electric Co., the buyout specialist got less leverage that it would have done a year ago, according to people with knowledge of the matter. That’s even after tapping more than 30 lenders, including private credit funds, to secure some of the debt financing.

In other cases, direct lenders have managed to cough up the cash. Meanwhile, KKR initially agreed to fund the purchase of French insurance broker April Group entirely with equity, before eventually tapping financing from a mix of direct lenders and banks.

Some banks have been able to chip away at the debt stuck on their balance sheets. In the final weeks of 2022, a Bank of America-led group offloaded $359 million of loans for Nielsen Holdings, while other lenders have sold about $1.4 billion of Citrix loans via block trades at steep discounts. It’s a similar story in Europe where lenders have managed to deal with the bulk of the overhang, though a financing backing the buyout of Royal DSM’s engineering materials is looming. While the sales did cement losses for the banks involved, the move freed up much-needed capital.

More sales could be coming. Goldman has had discussions with investors about selling around $4 billion of subordinated debt that lenders backing the buyout of Citrix Systems Inc. have held for months. The timing is contingent on the release of new audited Citrix financials, putting any potential trade on track for late January or early February.

“It would be a big shot in the arm to get those positions moved,” said Cade Thompson, head of US debt capital markets at KKR, referring to Citrix and Nielsen debt. “Having said that, we do not expect that the reduction of hung backlog alone will cause issuers to rush back into the syndicated market. A rally in the secondary is also needed in order to make a syndicated solution more viable.

The bottom line: the LBO machine is all jammed up, and as the Fed ramps up policy tightening it may take months to clear.

This just confirms there's big trouble brewing in private equity, something I've been warning of and it will impact banks' profitability.

And as Lewis Braham of Barron's reported a couple of weeks ago, floating-rate loan funds have promise and hidden risks:

With great risk comes great rewards. It’s a fundamental tenet of investing, but it has often not proven to be the case, whether in equities or, more recently, cryptocurrencies.

For one of the best money managers on the Street, the rewards of one kind of low-credit-quality debt—so-called floating-rate loans—are now well worth the risk.

“I would argue that the risk-adjusted returns of loans are better than equities today,” says David Giroux, manager of the T. Rowe Price Capital Appreciation fund (ticker: PRWCX) and a Barron’s Roundtable member. “You can earn high-single-digit returns with about 25% to 30% of the risk of the S&P 500. ”

Giroux is worth listening to. His $46 billion fund has beaten 99% of its peers in its category (the allocation: 50% to 70% equity) in the past 15 years. Although the fund will always have an equity tilt, the fact that he currently has a 15% weighting in loans is significant.

But the loans—which are issued by banks and other financial institutions—come with perils. They are called “floating rate” because the interest paid on them adjusts periodically, usually every 30 to 90 days, based on changes in widely accepted reference rates, such as the secured overnight financing rate (SOFR)—a measure of what it costs financial institutions to borrow cash overnight.

Loans also pay a predetermined fixed interest rate—or credit spread, as it is often called—over SOFR. Typically, the spread has been four to five percentage points over the reference rate during good times and higher during bad times, such as recessions. With a 0%-0.25% interest rate like we had at the start of 2022, a borrower might pay only 4% to 5% total—not too difficult for even a mediocre company.

Today, of course, interest rates have surged. The SOFR rate currently stands at 4.3%. That’s on par with the Federal Reserve’s 4.25%-4.50% rate it charges now to lend to other banks. The Fed is widely anticipated to keep raising rates to as much as 5%. Each increase puts additional pressure on borrowers; paying 4.3% plus the spread—8% or 9% total—isn’t so easy.

“Previously, interest rates were low, and that supported risk taking,” says Brian Juliano, who as head of the U.S. Leveraged Loan Team for PGIM Fixed Income helps oversee some $34 billion in loan investments, including the PGIM Floating Rate Income fund (FRFAX). The cheap-money environment led to much lower-quality debt issues. In debt credit ratings, a rating of BBB or higher is called investment grade. Loans are rated BB, B, and CCC in descending order—all below investment grade. The lower the rating, the greater the likelihood of default.

The percentage of loans rated BB has gone down “meaningfully” over the past decade, Juliano says. The loan market has less than 25% BB exposure, he notes, while the high-yield bond market has around 51%. The B and CCC companies “are highly levered companies that are economically sensitive. Certainly, in a recession, many of them will suffer,” he says.

Because of that, Juliano is “telling every investor that will listen that the low-quality portion of our market is risky.” He is largely steering clear of debt rated CCC.

In such an environment, active management is essential. Unlike stock indexes such as the S&P 500, which tracks stable blue-chip companies, floating-rate loan benchmarks such as the Morningstar LSTA US Leveraged Loan 100 Index, which is tracked by the popular Invesco Senior Loan exchange-traded fund (BKLN), invest in the largest loan issues. But the strongest companies often aren’t the largest loan issuers. Issuers of the largest loans can be the most overleveraged companies, which suffer the most as rates rise.

“When you have talk of recession, you’ve got to be super-concerned about leveraged loans,” says Eric Mollenhauer, co-manager of the $12 billion Fidelity Floating Rate High Income fund (FFRHX). “These companies can’t afford to have slowing sales.” Over the past 10 years, the Fidelity fund has produced a 3.1% annualized return, versus Invesco Senior Loan’s 2.2%.

That’s not to say indexing might not work in the short term. So far, defaults have been a modest 1.6% for loans and high-yield bonds in the 12 months ended Sept. 30, according to Standard & Poor’s Global Ratings, lower than their 4.1% historical average. S&P projects a 3.75% default rate in 2023 during what it expects to be a modest recession.

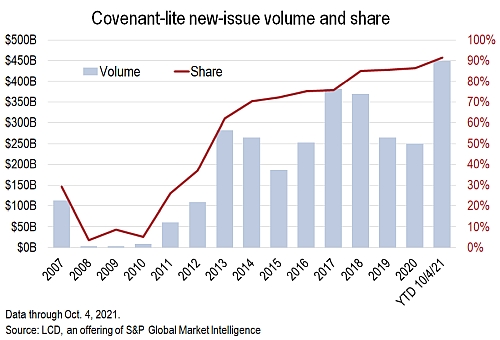

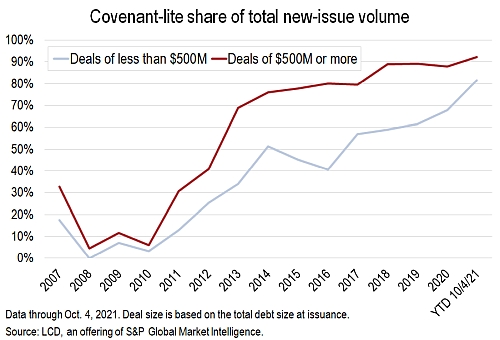

Yet there’s a dark cloud to that silver lining. Some 90% of the record $615 billion in loans issued in 2021 were what is known as “covenant-lite” loans with weaker default protections.

“Debt structures are different today,” says Nick Kraemer, head of rating performance analytics at S&P Global Ratings. “The debt cushion [in event of default] is much lighter for loans now than it was five or 10 years ago.” Only about 10% of loans issued were covenant-lite in 2011.

Despite the opportunities today, caution is merited.

Indeed, with a deep and protracted global recession on the horizon, caution is merited, it's time to toughen up your underwriting and focus on portfolio risks, not your relationship with issuers.

I would stick with my view that a recession this year is more likely than not.

— Lawrence H. Summers (@LHSummers) January 13, 2023

Watch my full interview with @DavidWestin tonight at 6pm on #WallStreetWeek @BloombergTV https://t.co/qlUnr8aSKZ via @economics

People got riled up back in May when I highlighted that lumber prices were down 500 or 600 at the time. I interpreted the collapse back in the Spring as the start of the housing "death spiral". I am not sure anyone will care now, but that's a sign of how much things have changed. pic.twitter.com/0dagzPADCc

— Francois Trahan (@FrancoisTrahan) January 10, 2023

This chart is dreadful when it comes to the outlook for stocks. Don't hate, I'm just calling it like it is and from a macro perspective the outlook is bad. This is really just another way to show the impact of Fed tightening on conditions and more specifically on liquidity. pic.twitter.com/nkBuF15Kxr

— Francois Trahan (@FrancoisTrahan) January 11, 2023

And I haven't even discussed cov-lite (covenant-lite) loans which survived the 2010 crisis and boomed since then, helping private equity's asset stripping business.

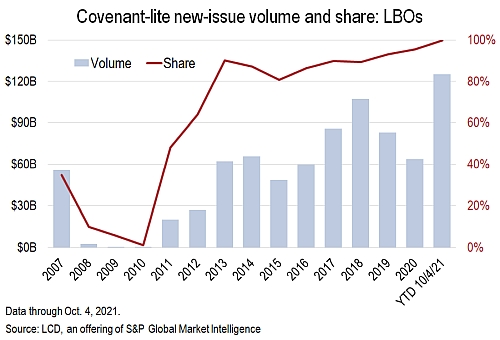

In October 2021, Abby Latour of S&P Global Market Market Intelligence noted that covenant-lite deals exceeded 90% of leveraged loan issuance, setting new high:

More than 90% of U.S. leveraged loans issued this year have been covenant-lite, a new record, further marking a two-decade-long transformation of the asset class in which nearly all newly issued loans have shed lender protections that once had been standard.

As of Oct. 4, the share of covenant-lite loans in the institutional loan market — which includes non-amortizing term debt, the type bought by CLOs — was 91%, the highest level on record, according to LCD.

Covenant-lite loans do not include maintenance covenants, which require borrowers to meet regular financial tests.

In absolute terms, year-to-date covenant-lite volume has already exceeded every full year on record. In 2000, covenant-lite loans represented roughly 1% of the market.

For loans backing LBOs, the share was even greater.

More broadly, some 86% of the $1.3 trillion in outstanding U.S. leveraged loans are covenant-lite, according to the S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loan Index. Likewise, that is a record.

The trend is worth noting because of the potential recovery levels. Covenant-lite facilities recover less than traditional term loans with maintenance covenants, an LCD analysis shows.

The trend toward covenant-lite debt in the syndicated loan market may also partly explain the rise of private credit loans. Private credit loans typically still offer lenders covenant protections, market sources say.

In recent years, private debt providers have taken market share from the syndicated loan market, LCD data suggests. The presence of covenants is one reason the structure is popular with lenders.

The vast majority of private loans still feature covenant protections, according to sources.

In fact, Stamps.com Inc. this week closed a $2.6 billion unitranche term loan backing an acquisition of the company by Thoma Bravo, the largest unitranche loan on record, according to LCD data. The term loan is covenant-lite. Behind the shift is competition among lenders and vast amounts of liquidity.

The key thing to note is cov-lite loans offer few protections to lenders when things turn south.

More recently, Abby Latour notes in her Pitchbook article back in February that the private debt structure worked in pandemic, but true test remains:

Close relationships with private credit lenders helped middle-market borrower companies obtain relief amid COVID-19 challenges. But the private debt market has yet to be tested by a prolonged crisis, according to an S&P Global Ratings report.

During pandemic closures, some borrower companies received covenant waivers or negotiated cash-saving measures, such as paying interest in-kind, from private debt providers. This feature of private credit, called "relationship-based lending," is often cited as a selling point for this type of financing.

The resulting relief helped some companies avoid what otherwise would have triggered a conventional default, but at times triggered the equivalent of selective default for middle-market CLO managers, according to the report, which analyzed companies found in middle-market CLOs.

"Periods of distress can be relatively painless and quick to work through—as we saw during the pandemic," said the report, titled "A Credit-Cycle Turn Could Expose Vulnerabilities In The Middle Market," published Feb. 9.

"It remains difficult to assess just how much long-term risk exists and how vulnerable the borrowers would be in the event of a credit crisis," it added. "The resilience of this market hasn't been truly tested in a protracted credit crisis."

Middle market CLOs generally contain loans to smaller companies that aren't rated. S&P Global Ratings estimates an equivalent designation on unrated loans, a so-called CE, or credit estimate. CE designations are lower case, as opposed to upper case for actual S&P Global ratings. S&P Global Ratings reviewed more than 1,500 companies for the purpose of assigning credit estimates.

Nearly three-quarters of middle-market entities reviewed by S&P Global Ratings in 2021 had the equivalent of a B- rating, a level that is roughly unchanged from prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

S&P Global Ratings estimates the median EBITDA for the middle market companies reviewed was $24 million, and the median adjusted debt was roughly $175 million. The largest subsector represented was health care providers, followed by software and commercial services, the report said.

The companies are majority owned by private equity firms (~94%), the report said. Notably, the top five private equity firms own just 7% of the entities reviewed, indicating the rest are dispersed widely among the nearly 350 in total private equity firms that own these companies, the report said.

Direct lending has attracted new entrants in part due to higher yields compared to other fixed-income asset classes and better loan documentation terms.

"One of the risks in the overall private debt market is nobody is quite sure how big it is or who ultimately holds the risk given how the risk is distributed. Its growth in recent years suggests it has attracted new crossover investors in search of yield," the report said.

"Consequently, problems in the private markets could ripple through to the more transparent and much-larger syndicated market."

Much depended on the asset managers themselves, including the quality of underwriting, portfolio management, and restructuring capabilities, the report said.

"A slowdown in economic growth coupled with inflation pressures and rising interest rates—and the consequent pressure on margins—could weigh heavily on some weaker companies with low coverage ratios," the report said.

All this to say if I were sitting on the Board of any major Canadian pension fund with a huge private debt book, I'd ask to see second-lien exposure in unitranche loans and ask that it be independently verified by a highly qualified and independent third party.

And again, funds like CPP Investments and PSP Investments have very qualified and experienced people in their private credit teams, I can only imagine what is going on at US public pension funds farming this out to PE funds or credit funds.

The next major debt crisis, like the previous one, will hit everyone hard but it's always the less sophisticated institutional investors who get clobbered the hardest because they came late to the private debt party and don't have the internal expertise to properly assess the embedded risks in their unitranche debt portfolios.

And the next time someone tells you private debt is a great asset class that hedges against inflation and has little to no risk, make sure you correct them on the "little to no risk part."

Like I keep warning my readers, this is a year to worry A LOT about risks across public and private markets.

When the next debt crisis hits, liquidity will dry up fast and all these illiquid loans will be selling for pennies on the dollar.

Large sophisticated pension funds will seize this opportunity to buy loans they think are being sold unjustly hard but many other less sophisticated pensions will get whacked hard.

So, maybe it's good that OTPP and HOOPP are only now "exploring" private debt as an asset class, they can sit patiently and invest right after the next default wave strikes. The same goes for BCI.

Let me wrap it up there but before I do, one risk expert told me to track the VanEck BDC Income ETF (BIZD):

The fund normally invests at least 80% of its total assets in securities that comprise the fund's benchmark index. The index is comprised of BDCs. BDCs are vehicles whose principal business is to invest in, lend capital to or provide services to privately-held companies or thinly traded U.S. public companies (basically middle-market companies which private equity firms lend to).

If you look at the holdings, you'll see Ares Capital, KKR Capital, Owl Rock Capital and more.

The risk expert told me:

BIZD and others flow through a fairly high dividend (11%), since the underlying middle market loans are done at high rates. And the BDCs, acting as “banks”, use leverage. However, I read an interesting article not too long ago that showed that the default rate of the underlying companies was high enough that the total return of a BDC index was *lower* than just buying high yield bonds. About the same level of volatility/drawdown, but lower return.

Nevertheless, if you are watching things like high yield bond/loan ETFs for changes in trend and things like that, as a close second you might want to watch BDCs. Stress in Private Equity lending may have a market outlet in those kinds of companies declining.

I thank this person for sharing BIZD with my readers.

Below, Private equity firms are increasingly turning to an obscure type of loan, once almost exclusively used to finance smaller deals, to fund larger and larger buyouts. Yet a growing number of analysts and investors warn the debt may be riskier than it appears. Bloomberg's Kelsey Butler reports on "Bloomberg Markets."

Second, investors who once flocked to the loans that financed the takeover of Envision Health ended up fighting over crumbs. Eliza Ronalds-Hannon examines what this signals about the lending market on "Bloomberg Markets: The Close."

Third, Warren Buffett is well-known for promoting the clear success of value investing, but one lesser known attitude he holds is his disdain for private equity firms. In this video, Buffett and Charlie Munger explain why they dislike private equity and so-called "alternative investments".

As I stated on LinkedIn earlier:

He's right which is why the bulk of the big money made in private equity at Canada's large pension funds is made in co-investments where they pay no fees, not in their fund investments where they pay big fees. But to gain access to co-investments to lower fee drag, you need to invest in funds and you need to hire experienced people and compensate them properly so they can analyze co-investments fast. Also, pensions have a long investment horizon so they can adopt the Warren Buffett approach and keep good companies in their books a long time, longer than the life of a PE fund (3-5 years).

Fourth, a panel discussion from the Milken Institute which took place three years ago on the age of private equity and credit.

Fifth, TD Securities Global Head of Rates Strategy Priya Misra says the Federal Reserve is going to be reluctant to stop hiking and predicts a 50 basis point rate increase in February. Speaking with Jonathan Ferro on "Bloomberg The Open," Misra says inflation has clearly peaked but markets are a little too optimistic about the decline in service inflation.Sixth, CNBC's Steve Liesman joins 'Squawk Box' to discuss inflation projections, growing tensions between the market and the Fed, and the potential market response to upcoming Fed funds rates.

Lastly, former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers says the Federal Reserve's fight against inflation is "much, much closer to being done," while cautioning that a US recession for this year still looms. He speaks on Bloomberg Television’s “Wall Street Week” with David Westin.

Comments

Post a Comment