Canadian Pension Funds Exposed to Northvolt's Collapse

For Northvolt AB, the Swedish startup that became a poster child for Europe’s electric-driving future, the route to collapse started in June when BMW AG cancelled a multi-billion-dollar order:

Back then, few saw the significance of the move, which effectively started a countdown that would culminate in a Chapter 11 filing less than six months later. Northvolt scrambled to keep the financing flowing, but as Germany’s car industry fell deeper into its own crisis, it became clear orders would dry up.

The company responded to the lost revenue by retrenching expansion plans and slashing jobs. By the time the last attempt at an emergency plan failed, investors who had poured in US$10 billion discovered only US$30 million cash was left.

Northvolt’s filing for bankruptcy protection in the United States, announced Thursday, marks one of the highest-profile setbacks for European industry against cheaper and nimbler Chinese and South Korean competition. The following day, co-founder and chief executive Peter Carlsson, who only a year ago had been trumpeting Northvolt as a possible initial public offering (IPO) candidate, resigned and warned the European Union risks falling behind on green projects.

The company needs as much as US$1.2 billion to finance its new business plan, Carlsson said, telling reporters that “we’ll regret it in 20 years if we’re not driving transition” to clean technologies.

In addition to BMW and Volkswagen AG, Northvolt’s top investors included Goldman Sachs’s asset management arm, Denmark’s biggest pension fund ATP, Baillie Gifford & Co. funds and a number of Swedish entities.

The Financial Times reported on Saturday that funds run by Goldman Sachs Asset Management are set to write down almost US$900 million at the end of the year. The investment was a minority one “through highly diversified funds,” Goldman said in an emailed statement, adding that its portfolios “have concentration limits to mitigate risks.”

One fund representative, who asked not to be named discussing private matters, said they were shocked at the speed with which Northvolt blew through its billions. As recently as July, the investor was confident of getting a return, but that changed in early August after getting a call from one of Northvolt’s owners, who warned that the battery maker could run out of cash by September.

The scale of the delays, and how bad things were with building budgets and construction projects remained hidden, the investor said, recounting how excel models and slide decks were used to conceal how empty the coffers had become.

The Swedish company now faces a task of restructuring, with a more focused operation set to emerge from the Chapter 11 process.

“A dilemma that these ambitious newcomers are facing is that from the get-go, they had to announce very large-scale plans in order to be attractive for financiers,” said Robert Heiler, senior manager at Porsche Consulting, part of the sportscar unit of Volkswagen, Northvolt’s top investor. “But it’s really difficult to scale up” various operations “all at the same time,” he said.

Just how badly Northvolt and its financiers misjudged the situation a year ago has now become evident. Last fall, the company invited investment banks to pitch for roles in an IPO that could have valued the battery maker at US$20 billion, the FT then reported.

A little over six months later, the IPO was pushed back from 2024, Bloomberg reported. Soon after that, VW’s truck unit, Scania, complained after Northvolt had trouble ramping up production volumes, and then BMW pulled its €2 billion (US$2.1 billion) contract to equip electric vehicles such as the i4 sedan and iX sports utility vehicle.

After repeated delays, the battery maker was unlikely to be able to produce the volumes BMW needed before 2026 — a year after predecessor models were set to be gradually phased out and almost three years after the original target date, a person familiar with the matter said, declining to be named discussing private information.

Around that time, a failure to close on an equity funding round meant that a US$5 billion green loan that was announced in January remained frozen, according to another person.

Even then, there was a chance for Northvolt to continue with plans for new battery plants in Germany, Sweden and Canada. In late June, Volkswagen — which owns 23 per cent of Northvolt — was prepared to step in, this person said. A representative for VW declined to comment.

But the German auto giant was facing a crisis of its own. By late summer, with EV sales stagnant in Europe and its lucrative Chinese business flagging, VW called for unprecedented factory closures in Germany.

Against the backdrop of potentially tens of thousands of layoffs at VW, Northvolt funding was off the table, and in August, VW withdrew from the equity plan, the person said. A Volkswagen representative declined to comment.

The German automaker, which had valued its Northvolt holding at the equivalent of more than US$730 million as of the end of 2023, then balked at committing to more battery purchases, people familiar with the matter said this month.

Still, work on a bridge funding deal continued, with an agreement coming close to fruition as recently as October. The US$300 million in emergency aid would have involved lenders, creditors and customers, but talks fell short.

“In this latest funding round, VW basically told us that they are not able to continue to capitalize us,” Carlsson said on Friday.

Northvolt’s debts include a US$330 million convertible loan from Volkswagen that’s due in December 2025, according to the bankruptcy court filing.

In its bid to reassure financiers, Northvolt nixed a planned expansion of its main plant in Skelleftea in northern Sweden and, in October, replaced the factory’s manager. But Carlsson acknowledges that he acted too slowly.

“I should have probably pulled the brake earlier on some of the expansion paths,” he said.

Northvolt’s big-swing approach will be second-guessed for years to come. But it won’t disappear in the immediate future. In its filing, the company said finding a strategic or financial partner is an overarching goal as it seeks to restructure the balance sheet and continue operations.

Governments — from Stockholm to Berlin — have rebuffed suggestions they’d spend taxpayer funds on a rescue.

German Economy Minister Robert Habeck, who had in June suggested Northvolt should build a second factory in his home country, on Saturday told German press agency DPA that he’s “cautiously optimistic” about the company’s future.

The relationship with Volkswagen continues. Scania CV AB remains a key Northvolt customer and will provide US$100 million in debtor-in-possession financing at a hefty interest rate of 16 per cent. Northvolt will also have access to about US$145 million in cash collateral. Battery plants under construction in Germany and Canada were left out of the bankruptcy, though the company said these projects will be postponed.

Northvolt is also making preparations in case it fails to raise funds for the future. Documents filed with the U.S. court show that it plans to “assess potential opportunities for a sale of some or all assets and has engaged Hilco Global to assist with an orderly liquidation process if necessary.”

Richard Milne and Harriet Agnew of the Financial Times also report Goldman Sachs takes $900mn hit on Northvolt investment:

Funds managed by Goldman Sachs will write off almost $900mn after Swedish battery maker Northvolt filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy this week.

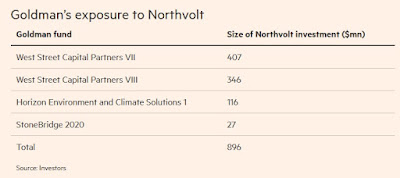

Goldman’s private equity funds have at least $896mn in exposure to Northvolt, making the US bank its second-largest shareholder. They will write that down to zero at the end of the year, according to letters to investors seen by the Financial Times.

The losses mark a sharp contrast to a bullish prediction just seven months ago by one of the Goldman funds, which told investors that its investment in Northvolt was worth 4.29 times what it had paid for it, and that this would increase to six times by next year.

Goldman said in a statement: “While we are one of many investors disappointed by this outcome, this was a minority investment through highly diversified funds. Our portfolios have concentration limits to mitigate risks.”

Goldman first invested in Northvolt in 2019 when, along with other investors including German carmaker Volkswagen, it led a $1bn Series B funding round that enabled Northvolt to build its first factory in northern Sweden, and fuel future expansion.

The funding round was hailed by Northvolt chief executive Peter Carlsson as “a great milestone for Northvolt” — then a four-year old start-up — and “a key moment for Europe” in its push to counter Asian dominance of battery making.

But Europe’s one-time big battery hope filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the US on Thursday and Carlsson resigned the following day, warning European politicians, companies and investors not to get cold feet on the green transition.

By Thursday the lossmaking Swedish group, which was Europe’s best-funded private start-up after raising $15bn from investors and governments, had just $30mn in cash — enough for a week’s operations — and $5.8bn in debt.

That day Goldman, which owns a 19 per cent stake in Northvolt through various funds, wrote to its investors explaining that it would mark down to zero its investments.

The bank, which had taken part in several subsequent funding rounds over the past five years, said that over the last several months it had been working with Northvolt’s customers, lenders and shareholders to secure short-term bridge financing to shore up the battery maker’s financial position, restructure its capital stack and raise longer-term financing to support a revised business plan.

But “despite our extensive efforts as a minority shareholder to bring Northvolt’s various shareholders together, a comprehensive solution was not found”, it said in the letters to shareholders.

Goldman’s private equity business was established in 1986 and sits within Goldman Sachs Asset Management, which has over $3tn in assets under supervision, including over $500bn in alternative investments such as private equity.Two buyout funds West Street Capital Partners VII and West Street Capital Partners VIII have $407mn and $346mn invested in Northvolt, respectively. Horizon Environment and Climate Solutions 1, a growth equity strategy touted as Goldman’s first direct private markets strategy dedicated to investing in climate and environmental solutions, has $116mn invested in Northvolt; and a fund called StoneBridge 2020 invested $27mn.

Goldman’s so-called 1869 fund, a vehicle that gives its network of former partners access to multiple private funds managed by the fund’s asset management division, also had a small amount of exposure to Northvolt, because the fund has committed 25 per cent of its capital commitments to West Street Capital Partners VIII, investors said.

Goldman Sachs’ investment banking business is also a large creditor of Northvolt; the battery company owes it $4.78mn, according to its Chapter 11 filing.

Volkswagen is Northvolt’s largest shareholder with a 21 per cent stake and is likely to be nursing similar losses. It is listed as Northvolt’s second-largest creditor in the Chapter 11 filing due to a $355mn convertible note.

Some investors have privately complained that Goldman and other funds pushed them hard to back Northvolt. They have also said that this, combined with Northvolt’s bankruptcy, could affect investors’ desire to support the green transition.

Northvolt has said it needs $1-1.2bn extra financing to exit Chapter 11 in the first quarter of next year, and is talking to various investors and companies about partnerships. By filing for Chapter 11 it can access finance including $145mn in cash and $100mn from Swedish truckmaker Scania.

The Swedish group struggled to expand production in its sole factory in Skellefteå in northern Sweden. Executives conceded it should have scaled back earlier expansion plans to build additional facilities in Germany and Canada which were backed by extensive subsidies from each country’s government.

What a mess, Northvolt's collapse has hit many investors, including Canadian pension funds.

Last week, Jeffrey Jones and James Bradshaw of the Globe and Mail report on their exposure to the struggling EV battery maker:

Several Canadian pension funds have sizable financial exposure in the event of a bankruptcy filing by Northvolt AB, the Swedish battery maker that is burning through cash as growth in demand for electric vehicles lags expectations.

Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, Investment Management Corp. of Ontario (IMCO), Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System and Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec participated in US$2.3-billion in convertible debt financings for Stockholm-based Northvolt, joining major automakers and financial institutions to support the European battery hope as its future looked bright. OMERS also bought an undisclosed number of Northvolt shares in 2021.

The Financial Times reported on Sunday that Northvolt is considering seeking protection from creditors in the coming days after talks about a rescue package collapsed. The company is still trying to secure short-term financing, but time is getting short, the FT said, quoting unnamed people involved in the negotiations.

Northvolt has suffered this year as EV demand growth slowed and a US$2.15-billion battery order was cancelled. In recent months, it has cut a fifth of its staff and shelved many of its expansion plans. Meanwhile, the fate of a $7-billion factory planned for Quebec has yet to be decided.

Northvolt said little about its current predicament when contacted by The Globe and Mail on Monday. “Financing negotiations are ongoing,” Northvolt spokesperson Emmanuelle Rouillard-Moreau said in an e-mail. “We are maintaining close communication with our investors and key partners. We will share updates and the outcome of these discussions once decisions have been finalized.”

The terms of Northvolt’s convertible debt – including under what circumstances it would be swapped for equity – have not been disclosed, which makes it hard to gauge where the four Canadian pension funds rank in terms of seniority in the event of a bankruptcy, or how much of their initial investments are at risk of being wiped out. Lenders typically rank ahead of equity owners when a company is restructured.

Northvolt’s ownership group also includes some of the biggest automotive and financial names, such as Volkswagen AG, Bayerische Motoren Werke AG and Goldman Sachs. The latter was said to be leading ill-fated rescue-package talks that were aimed at securing a reported US$300-million.

The total exposure among the Canadian pension funds is murky, making it difficult to glean the precise values of the funds’ investments from public disclosures. The four pension-fund managers participated in a series of debt issues in 2023, including a US$400-million investment from IMCO. CPPIB invested US$55-million, while OMERS and BlackRock Inc., which is the world’s largest asset manager, also participated as Northvolt expanded its existing US$1.1-billion convertible debt program to US$2.3-billion.

In November, 2023, the Caisse took on US$150-million in convertible debt.

OMERS was an earlier backer of the battery maker and has made three investments, starting with the purchase of an undisclosed stake in a US$2.75-billion private placement of equity alongside a host of other investors, including Swedish pension funds, Goldman Sachs and Volkswagen. OMERS has not disclosed the size of its equity position.

Spokespeople for OMERS, CPPIB, IMCO and the Caisse all declined to comment beyond confirming investments that were publicly announced.

In September, Northvolt announced it was cutting its Swedish work force by 1,600 and suspending a number of its expansion projects. It retreated from its growth strategy as automakers such as General Motors Co. GM-N, Ford Motor Co. F-N, Volvo Car AB and Volkswagen tempered their EV outlooks and spending to deal with high capital costs and some resistance among car buyers, who face sticker shock and still-spotty charging infrastructure. In June, BMW cancelled a US$2.15-billion order for Northvolt battery cells.

All of this turmoil has raised questions about the Quebec plant, which has been awarded billions of dollars in loans and production incentives from the federal and Quebec governments. Northvolt has said that it is conducting a strategic review of the facility in Saint-Basile-le-Grand, Que., and results are expected in the coming weeks.

Well, I think today's message is clear, Northvolt is in survival mode and will delay projects to build battery plants in Canada and Germany.

How could this happen? How did a company widely viewed as the preeminent player in the energy transition market, one coveted by world-class investors, end up collapsing so fast after billions were poured to finance its operations?

From the first article:

“A dilemma that these ambitious newcomers are facing is that from the get-go, they had to announce very large-scale plans in order to be attractive for financiers,” said Robert Heiler, senior manager at Porsche Consulting, part of the sportscar unit of Volkswagen, Northvolt’s top investor. “But it’s really difficult to scale up” various operations “all at the same time,” he said.

Add to this the collapse in demand for EVs and the surge in supply of EV batteries from China and South Korea and you have a recipe for disaster.

In short, everything that can go wrong for Northvolt and its investors did go wrong and now (equity) investors got wiped out, suffering the biggest losses:

For their part, Canadian pension funds were exposed -- OMERS probably the most and CPP Investments and CDPQ the least with IMCO somewhere in the middle (need to verify this) -- but they provided debt financing in the form of convertible bonds so they will get hit hard but not totally wiped out (depends on where they stand in the debt seniority chain).

However, governments will feel the sting too, in particular the Quebec and federal government and taxpayers who backed these battery plants to the tunes of billions in subsidies.

And Northvolt's collapse is the tip of the iceberg, others might follow as EV demand plummets.

It was exactly a year ago that Peter Zimonjic of CBC News reported EV battery deals to cost $5.8B more due to lost corporate tax on subsidies, budget officer says:

Provincial and federal financial support for electric vehicle battery production will cost $5.8 billion more than government projections due to tax treatment of subsidies, the Parliamentary Budget Office said Friday morning.

The PBO report says the shortfall of $5.8 billion over 10 years can be attributed to lost corporate income because the Canadian deal has to keep pace with the Advanced Manufacturing Production Credit (AMPC) in the United States.

Under the U.S. deal, manufacturers get a tax credit, based on a calculation of per kilowatt-hour of energy, but in Canada that financial support per kilowatt-hour is delivered through a taxable subsidy.

"Therefore, under existing law in Canada, these payments would be subject to applicable federal and provincial corporate income tax," the report said.

The PBO report makes the assumption that to stay on par with the U.S. AMPC, the subsidies will be exempt from federal and provincial taxes, which would cost about $5.8 billion in tax revenue.

An analysis of government support for the EV battery deals with Northvolt, Volkswagen and Stellantis-LGES said that over the next 10 years, that support will amount to $43.6 billion, rather than the announced costs of $37.7 billion.

The deals with the three manufacturers amount to production subsidies of $32.8 billion, with an additional $4.9 billion in support to build the facilities.

"Of the $43.6 billion in total costs, we estimate that $26.9 billion (62 per cent) in costs will be incurred by the federal government and $16.7 billion (38 per cent) will fall on the provincial governments of Ontario and Quebec," the report said.

Break-even estimates

The report, which also looked at how long it will take for governments to break even on their investments, found that the Northvolt deal has a break-even time of 11 years, two years longer than the federal government's estimate.

The break-even time for the $13.2-billion Volkswagen deal is 15 years, while the break-even time for the $15-billion Stellantis-LGES deal was pegged at 23 years, the report said.

In the PBO's September report, Yves Giroux, the parliamentary budget officer, said the government's shorter break-even timeline estimate relied on modelling from the Trillium Network for Advanced Manufacturing and Clean Energy Canada, which included investments and assumed production increases in other areas of the EV supply chain.

Giroux's reports only looked at cell and module manufacturing and not the expected revenue from spillover impacts on the economy as a whole.

The report also assumes that government investments will be debt-financed and therefore will incur public debt charges over the next decade that could amount to $6.6 billion.

Pros and cons

Ian Lee, a professor at Carleton University's Sprott School of Business, told CBC news the PBO was right to exclude calculations estimating the economic benefits of strengthened supply chains because they can be misleading.

"This is political spin masquerading as serious econometric analysis. This is why the PBO rejected it," he said. "Anyone can provide any number to produce the number they want … It is not evidence based but pure speculation that appears credible."

Lee described the possible economic advantages of developing EV battery and car manufacturing as "investor hype" and said that Canada's auto sector is in decline and the investment "will ultimately fail."

Economist Jim Stanford, director of the B.C. based Centre for Future Work, told CBC News the PBO report misses the point of the subsidies by choosing to evaluate them as an investment, rather than an attempt to ensure the economy is well-placed to capitalize on the green transition.

"The government is supporting these plants because that is what's required to maintain the auto industry, and all of the economic and social benefits that it generates, as it transitions to EVs," he told CBC.

The PBO's "cost benefit lens for all of these reports is ridiculously narrow, and misses the point of why governments are doing this," he added.

Stanford said that without government subsidies to draw in foreign investment, Canada's auto industry would disappear within 15 years. To get better value for the EV investment program, the PBO should compare the subsidy programs to doing nothing and allowing the industry to fail, he said.

Stanford also said that ignoring the economic impacts to the overall economy of the EV subsidy program is the "fatal flaw" in the PBO report.

The 3 big deals

The new manufacturing facility to be built by Northvolt, a Swedish battery giant, will occupy 170 hectares — an area the size of more than 300 football fields — on Montreal's South Shore, in a parcel of land spanning two communities.

The combined production and construction incentives total up to $4.6 billion for the project — one-third of which will come from Quebec — as long as similar incentives remain in place in the U.S.

In the spring, the federal government announced $13.2 billion in production subsidies over the next 10 years to build a battery plant in St. Thomas, Ont. That plant will be the size of 391 football fields and bring auto jobs to the region.

Stellantis-LGES halted construction on a Windsor, Ont., battery plant this summer, saying the provincial and federal governments would need to come through with more than the initial investment of $500 million. Construction resumed after the governments announced up to $15 billion in subsidies.

That plant is expected to open in 2024 and employ about 2,500 people.

There's no question governments need to provide subsidies but every time a Nortvolt or another EV battery project fails, it costs taxpayers billions.

Still, the collapse of Canada's auto sector will cost thousands of jobs and lost income taxes (revenue for the government), not to mention set the country back so governments are damned if they do, damned if they don't (provide subsidies).

One thing is clear however, Northvolt was extremely poorly managed and Peter Carlsonn was right to step down.

The energy transition will happen with or without Northvolt but it will be a real shame if this company which was at the forefront of so many good things in the energy transition spectrum isn't part of this journey.

At the end of the day, economics rules the day, you can't expand forever and expect taxpayers and investors to cough up more money. At one point, you need to show results.

Below, Northvolt's financial collapse deals a blow to Europe's plan to set up its own battery industry to power electric cars, stirring a debate about whether it needs to do more to attract investment as startups struggle to catch up with Chinese rivals.

Next, Swedish battery company Northvolt has filed for bankruptcy in the US, in a setback for Europe’s ambitions to compete with the largest Asian producers of lithium ion batteries for electric vehicles. In this video Benchmark analyst Shivangee Chauhan discusses what it means for European battery production.

Third, Northvolt bankruptcy: "Its what's called a Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection," but what doe sit mean? CGTN Europe interviewed Daniel Harrison, Automotive analyst, Ultima Media.

Lastly, Swedish EV battery maker Northvolt has officially filed for bankruptcy protection in the U.S. Heather Wright on what this means for Canada.

Comments

Post a Comment