Pensions Bet Big With Private Equity?

On the 13th floor of a sleek downtown office building in Austin, Texas, the trading desks are manned overnight. The chief investment officer favors cowboy boots made of elephant skin. And when a bet pays off, even the secretaries can be entitled to bonuses.

The office's occupant isn't a high-flying hedge fund but the Teacher Retirement System of Texas, a public pension fund with 1.3 million members including schoolteachers, bus drivers and cafeteria workers across the state.There is a lot to digest in this article. Think Texas Teachers is doing many interesting things in their investments but I have also questioned previous deals like the equity stake in Bridgewater. As far as their compensation, I've covered this too in a comment on pay and performance at public plans.

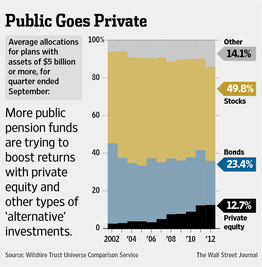

It is a sign of the times. Numerous pension funds are still struggling to make up investment losses from the financial crisis. Rather than reduce risks in the wake of those declines, many are getting aggressive. They are loading up on private equity and other nontraditional investments that promise high, steady returns in the face of low interest rates and a volatile stock market.

The $114bn Texas fund has hit the trend particularly hard. It now boasts some of the splashiest bets in the industry, having committed about $30bn to private equity, real estate and other so-called alternatives since early 2008. That makes it the biggest such investor among the 10 largest U.S. public pensions, according to data provider Preqin. Those funds have an average alternatives allocation of 21%.

Not all pension managers are in on the action. Some funds are wary of the high management fees often charged by private-equity and hedge-fund firms. And while a large fund like Texas' may have access to marquee investors, smaller pensions may have trouble getting an audience with the best performing firms.

Even in Texas, there isn't exactly consensus. Critics worry that the teachers' benefits are leaning too heavily on the esoteric investments, which can be less liquid and less transparent than stocks and bonds. Another sticking point is the fund's generous bonus culture—a contrast against the pensioners, who haven't seen a cost-of-living raise in more than a decade.

"I have problems with these alternatives," says former Texas State Sen. Steve Ogden, who owns an oil and gas company. "It's one of these 'trust me' investments."

And yet the strategy has helped to turbocharge the Texas pension, with returns from private equity averaging 4.8% and 15.6% over the past five-year and three-year periods respectively.

Including all assets, the pension's annual return from Dec. 31, 2007, to Dec. 31, 2012, was 3.1%—better than the median preliminary return of 2.46% among large public funds, according to Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service.

Texas pension officials say private equity helped offset declines in its other investments. Britt Harris, the pension's chief investment officer, says he aims to "smash" the stereotype that government pension funds are on the losing end of most investments.

In November 2011, the Texas fund made one of the largest single commitments in the private-equity industry's history, investing $3bn in KKR and another $3bn in Apollo Global Management. Three months later, Texas teachers bought a $250m stake in the world's biggest hedge-fund firm, Bridgewater Associates—a first such equity stake for a US public pension.

For the fiscal year ended Aug. 31, the Texas teachers fund had a 7.6% return, and pension officials say they expect their bet on alternatives can help the fund hit its 8% annual target return over the long term. Over a ten-year period ending Aug. 31, 2012, the fund has had an annual fiscal year return of 7.4%.

Other large pension funds aren't so optimistic. Sticking to a return of 8% or more is "taking a big risk with one's ability to pay for benefits,' says Richard Ravitch, co-chair of the State Budget Crisis Task Force, a nonpartisan research group. Since 2009, one-third of state pension plans have scaled back their return goals, according to the National Association of State Retirement Administrators.

The reason: In some states, like California, failure to hit the target return puts taxpayers on the line to make up the difference.

California's giant public employee pension fund, Calpers, had made an aggressive push into alternative investments such as real estate, representing about one-tenth of its assets. But many of those real-estate holdings, particularly in housing, suffered big losses during the financial crisis.

If Texas misses its mark, state officials could seek to cut benefits or switch newly hired teachers from traditional pensions to less generous 401(k)-type plans. Similar proposals in other states have met with stiff resistance from labour unions.

Retired education workers in Texas, on average, receive an annual pension of $21,730. Most former educators don't receive Social Security, making their total retirement benefits among the lowest of the big public pension systems.

"If new teachers are forced to switch to 401(k)s," says Tim Lee, head of the retired teachers association, "they will end up in poverty."

Unlike many state pensions, the Texas teachers fund is in relatively solid shape. It is 82% funded, meaning there are 82 cents of assets covering $1 of liabilities, up from a low of 68% in February 2009, during the depths of the financial crisis. The average funding level among large public pension systems nationally is about 76%. Contributions from teachers and the state are identical, at 6.4% of employee salaries. The balance comes from investment earnings.

Still, the pension had a $26 billion shortfall, as measured at the end of August, caused in large part by big stock market losses during the financial crisis and increases to benefits for future retirees.

Harris, the pension's CIO since late 2006, says over the long term the fund can keep hitting its target, but "getting to [the 8% target level] over the next five to 10 years is going to be tough," he acknowledges.

With so much riding on returns, Harris has created an investment operation that looks and feels more like a hedge fund than a government agency. The office lobby buzzes with a flat-screen television that hangs next to photos of school children. Two of the fund's traders work into the night from a windowless room, following the markets in Asia and Europe. Staff—including secretaries—can score annual bonuses provided the pension beats its peers by just a small fraction.

Mr. Harris, whose mother is a retired Texas schoolteacher, once managed pension investments for corporations like Verizon and briefly served as CEO of Bridgewater. Last year, he was rewarded by the fund with a bonus totalling $483,753. Harris recused himself from the pension's deal to buy the Bridgewater stake.

Fund officials say the bonuses are necessary to attract an investment staff that can compete with the most accomplished investors around the world.

For decades, the Teacher Retirement System favoured a mild brew of stocks and bonds. But starting in 2000, Gov. Rick Perry, a Republican, put real-estate developers and other investors on the pension system's board. Five of the nine current trustees are investment professionals.

"We had to have a more progressive system of investing if retirees were ever going to get a cost-of-living increase,' says Linus Wright, a former pension board member and former superintendent of the Dallas schools.

Between 2005 and 2007, as Texas and other states were ratcheting up their private-equity investments, state legislatures passed laws preventing certain information about the holdings from being disclosed to the public. Some private-equity firms insisted on these measures before approving investments from pension funds, says William Kelly, a partner at Nixon Peabody LLP, who works with both pensions and private-equity firms on disclosure issues.

"We are not your average investor,' said Steve LeBlanc, the former head of private-equity investments, who left the Texas pension fund in April to return to the private sector.

To help train managers, Harris employed some unusual tactics. He hired former law-enforcement agents to teach his staff how to tell if someone is being less than truthful when touting investments.

One strategy: Always have two members of the pension-fund staff in the room. That way, one person can listen to what the Wall Street salesperson is saying and the other can watch his or her body language.

"We know we are up against the most highly resourced, most sophisticated sales effort probably in the whole world,' says Harris. "But we have brought people in here who are equal to or better than what you find on Wall Street."

During the financial crisis, the Texas teachers fund showed its mettle by making investments that many pension funds couldn't stomach.

As the credit crisis escalated in late 2008, the Texas pension board authorised an investment of up to $5bn in inexpensive, high-yielding debt.

It was a large amount, even for a Texas-size fund. Still, some pension officials had an appetite for more. One pension board trustee said he was comfortable investing up to half of the pension fund's assets in the cheap debt, recalls board chairman David Kelly.

As the recession deepened and fear roiled the debt markets, the pension's investments in residential mortgages, corporate bonds and bank loans, totalling $2.6bn , lost value in the early part of 2009. The pension fund held on to the debt, which eventually gained 15%.

"Everyone, as we like to say down here, cowboyed up," says Kelly, a former Salomon Brothers banker and real-estate executive.

Ogden, the former legislator, had tried to convince lawmakers to reconsider the teachers' investment strategy. Instead, officials opted to extend it to at least 2018 while voting to allow the fund to double its hedge-fund investments.

"They found no smoking gun to convince them to cancel the program,' recalls Ogden.

The pension board also took steps to reduce the red tape in the investment process, giving its senior investment staff "quick-strike authority" to invest up to $1bn without full board approval.

LeBlanc used this authority in the spring of 2010 when he says he got a call from a friend at Paulson & Co., the firm run by hedge-fund star John Paulson. The friend asked: Would the teachers fund join Paulson in providing national mall operator General Growth Properties with new funding to exit bankruptcy?

Paulson lost out on the deal, but the pension fund plowed ahead, joining another group of Wall Street firms that agreed to pay about $10 per share for a large stake in General Growth. The risk was that the shares could fall as the company exited bankruptcy in a difficult retail market. After three weeks of due diligence, the Texas pension made an initial commitment to invest $500m in General Growth.

"No one moved as quickly as they could,' says Adam Metz, General Growth's former CEO.

General Growth turned out to be a big winner. The mall company's shares are worth about $19 today, an 85% gain for the pension fund.

Despite that particular coup, doubters wonder if the strategy is sustainable. "They may think they are the smartest and best investors, but this system cannot work in the long term," says former Rep. Warren Chisum, who in the last legislative session proposed switching new teachers to 401(k) plans.

Pensions officials, such as Harris, say the risks of the alternatives are manageable because the pension fund has ample liquidity to keep paying benefits in the event of big losses.

Texas educators have little choice but to support the pension fund's aggressive investment strategy and Wall Street-style bonuses. But retiree raises can't materialise until the system's funding level improves—to an estimated 90% from its current 82%. One solution, not popular with educators, is to increase the retirement age for teachers to help make up the fund's shortfall.

In the meantime, educators like Vella Pallette, a retired elementary-schoolteacher from the tiny Central Texas town of May, are in limbo. The 78-year-old's $2,000 monthly pension check is her sole source of income. "A little more money," she says, "sure would help."

Chris Tobe of Stable Value Consultants was a lot harsher, deriding this article as another "WSJ puff piece on TRS." He told me if you want the real story on Texas Teachers, you have to read an article from the Dallas News on how secrecy cloaks placement agents’ role in Texas public pension fund investments.

Leaving placement agent scandals aside, the article is all also about private equity and how plans are shifting more and more assets into alternatives to meet their 8% bogey. In finance, there is no free lunch. If pensions want to achieve their actuarial target return to keep the cost of the plan down for all stakeholders, then they need to invest in both public and private markets. Shifting away from a defined-benefit to defined-contribution is dumb and will only condemn teachers to pension poverty.

However, with interest rates at a historic low, that 8% bogey will be extremely difficult to meet in the next decade. Shifting more assets into private equity might help pensions meet their target return but it also exposes them to other risks such as illiquidity risk, valuation risk, manager selection risk, lack of transparency and potential conflicts of interest.

It's amazing how few US public pension plans understand these risks. CalPERS got creamed in real estate during the last crisis, losing 40% in co-mingled funds that were investing in risky mortgages. In private equity, they were invested in over 350 funds (crazy!!!), paying out enormous fees and getting mediocre benchmark returns.

The task of cleaning up that mess fell onto Réal Desrochers who was appointed as head of PE back in May 2011. There is still a lot of work to do and as I mentioned in a recent comment on CalPERS's 2012 returns, private equity has benchmark issues as they significantly underperformed their benchmark which delivered a whopping 28.5% (12.2% vs 28.5%). There is a problem with that benchmark.

Getting the benchmark right is important for public pension funds because that is how they determine compensation. Unfortunately, private equity benchmarking isn't as easy as it sounds because different pensions have different allocations in sub-asset classes and different approaches to private equity investments.

This morning I received a call from Neil Petroff, CIO at Ontario Teachers' and we had an interesting discussion on intelligent use of leverage at pensions, benchmarks and compensation. Neil told me that their real estate investments returned 18% last year, below the benchmark but far outperforming their peers. Given the circumstances, the board agreed with him that compensation can't solely be based on them underperforming the real estate benchmark.

As far as private equity, Neil agrees with me that the benchmark should be a spread over some public market index (even if this isn't perfect). If a pension fund invests mostly in US buyouts, then it should be a spread over the S&P500, if it's more global, it should be a spread over MSCI World. Even if there is some credit and venture capital in the portfolio, all you have to do is adjust the spread accordingly with the risk of the underlying portfolio.

Interestingly, Neil also told me that after 2008, compensation was adjusted so that long-term comp -- the bulk of the comp -- is based on the Fund's overall performance and short-term comp is based on the group's performance. "This encourages a lot more collaboration among investment departments and reduces blow-up risk from any one department." The senior VPs all get together once a month to discuss big investments they're considering and each have an input before Neil signs off and presents them to the board.

As far as private equity, Ontario Teachers' invests in direct deals, co-invests with private equity funds and does some fund investments when it sells stakes and needs to keep target allocation. He told me unlike 2011, most pensions didn't make money in private equity last year because public market delivered 14-15%, so achieving a spread over public equities was difficult.

He also told me that rumors that Ontario Teachers' ignored 2008 losses in their compensation to retain staff are "totally false." He said his long-term bonus took a "big hit" in 2009 and that so did that of other senior officers. This is why compensation was changed to focus on the Fund's overall results.

Moreover, as far as private equity, they don't collect bonus if they just beat the benchmark. They first have to recoup all the costs -- roughly 7% -- before they can collect bonus (think he's talking about an internal hurdle rate). This makes perfect sense but you'd be shocked to find out how many pension funds do not take costs into account when compensating staff in private investments.

We talked about a news article which came out today which states Ontario Teachers' is interested in pipelines. Neil told me he gets bombarded by calls every time some article comes out but if it makes sense, they look at it regardless of whether it's private or public. "We're interested in everything that makes sense."

Finally, he told me that investment staff logged in millions of miles traveling last year, meeting GPs, going to board meetings in companies they bought, and cultivating new and old relationships with GPs and LPs."We're not looking to be number one every year but we want to consistently be among the top three. Everyone is trying to copy us but it will take them seven to ten years before they reach the point where we're at now."

I think Neil Petroff is one of sharpest pension fund managers in the world and a very nice guy. Thank him for taking the time to speak with me. Only wish he would write a book on pensions, covering intelligent use of leverage, private equity, real estate, hedge funds, and a whole host of issues, including proper compensation and how to cultivate a great environment at a pension fund.

Below, Stephen Schwarzman, chief executive officer of Blackstone Group LP, and one of the real fiscal cliff deal winners, talks about the private-equity market, the global economy and President Barack Obama's policies. He speaks with Erik Schatzker on Bloomberg Television's "Surveillance" at the sidelines of the World Economic Forum's annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland.

And Jim Leech, president and CEO of Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan, tells CNBC an energy self-sufficient U.S. could cause a "seismic" market shift. Indeed, it will be a global game changer and agree with him, 2013 should be a good year for private equity.