Regulators Demanding More Disclosure From Private Equity and Hedge Funds

Australian pension funds need to improve how they value private equity, the sector's regulator said on Monday after a review into the sector's treatment of Canva, an Australian technology startup whose lofty valuation tumbled last year.

Sydney-headquartered software firm Canva hit a peak valuation of $40 billion in late 2021, only to be revised sharply lower to $25.5 billion last August amid a downturn in technology stocks. Major funds including Aware Super and Hostplus were investors.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) on Monday said while most funds had "appropriate" valuation practices for Canva, "several areas required improvement", including instances where boards were not given appropriate information or were unwilling to challenge what they had been told.

The regulator also said some valuation policies needed clearer triggers for when to do an interim valuation.

"Through our supervision activities, APRA has continued to address these issues with RSE licensees since the conclusion of the review," APRA said in a release that did not name any funds.

Private assets are popular in Australia's A$2.4 trillion professional pension sector, with some funds holding almost half their assets in private markets. Since 2021, the regulator has pushed the sector to improve how it values assets that range from venture capital to office blocks.

In July, the regulator published new guidelines for the sector, which among other things, called for portfolio valuations each quarter.

Regulators are pushing private equity firms to do a better job when it comes to valuing their assets.

Carolina Mandl and Chris Prentice of Reuters report US SEC overhauls rules for $20 trillion private fund industry:

The U.S. securities regulator on Wednesday adopted new rules that will shine a light on private equity and hedge fund expenses and fees, in what executives and lawyers said marks a sweeping overhaul for an industry long criticized for its opacity.

But in a partial victory for fund groups which opposed the rules, the Securities and Exchange Commission did not proceed with proposals that would have expanded funds' legal liability and outright banned arrangements that allow some investors special terms.

The securities regulator's five-member panel voted 3-2 to implement a number of new requirements aimed at increasing transparency, fairness and accountability in the private funds industry, which has more than doubled its assets over the past decade. The industry manages around $20 trillion in assets.

The new rules require private funds to issue quarterly fee and performance reports, and to disclose certain fee structures while barring giving some investors preferential treatment over redemptions and portfolio exposure. The rules also require funds to perform annual audits.

Advocacy groups have accused the private fund industry of unfair, conflicted and opaque practices that hurt everyday Americans who invest in such funds through their pensions.

"Investors, large or small, benefit from greater transparency, competition and integrity. It's not as if some state pension fund benefits from opacity," SEC Chair Gary Gensler told reporters after the panel's vote.

While the changes mark the biggest overhaul of industry rules in years, the SEC rowed back on some proposals after major players, including Citadel and Andreesen Horowitz, argued that the agency was overreaching its authority by attempting to bar long-established fee structures and liability terms.

The agency dropped a proposal to bar fees for services that are not performed, such as compliance expenses or costs defending against regulatory probes, and scrapped another that would have made it easier for investors to sue funds for misconduct.

The SEC had also proposed banning so-called "side letters," an industry practice through which funds can offer some investors special terms. Instead, it opted on Wednesday to require that fund managers disclose such agreements when they are financially material.

The SEC did, however, ban the practice of offering some investors special redemption terms.

Despite the softening of the original proposal, lawyers said the changes marked a sea change for the industry.

"This is still a sweeping series of rules for private fund managers that will have significant effects," said Kelly Koscuiszka, partner with Schulte Roth & Zabel law firm in New York.

The rules will go into effect in 60 days, although some will be phased in depending on the size of the fund. They will apply to new agreements, meaning the industry will not have to rewrite all existing contracts.

The Managed Funds Association industry group said it continues to have concerns that the new requirements will hike costs and curb investment opportunities.

The group will "work with our members to determine the appropriate next steps to protect the interests of alternative asset managers and their investors, including potential litigation," CEO Bryan Corbett said in a statement.

Did you catch this part: "Despite the softening of the original proposal, lawyers said the changes marked a sea change for the industry."

No kidding, private equity funds and hedge funds rule with impunity, they do not want more transparency and rules against clobbering investors with opaque fees.

In fact, there is already legal pushback from the industry.

Carolina Mandl of Reuters reports US private funds industry sues securities regulator over new rules:

Six private equity and hedge fund trade groups on Friday sued the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), arguing the agency overstepped its statutory authority when adopting sweeping new expense and disclosure rules last week.

SEC Chair Gary Gensler said the rules will increase transparency and competition in the private funds industry, which oversees around $20 trillion in assets and has been accused by advocacy groups of opacity and conflicts of interest.

An agency spokesperson said the SEC "undertakes rulemaking consistent with its authorities and laws governing the administrative process." It added it will defend the new rules in court.

The changes require private funds to issue quarterly fee and performance reports and to perform annual audits. They also require that funds disclose certain fee structures, and bar them from offering some investors preferential treatment when it comes to their portfolio exposures and ability to cash out.

"The rules exceed the Commission's statutory authority, were adopted without compliance with notice-and-comment requirements, and are otherwise arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, and contrary to law, all in violation of the Administrative Procedure Act," the associations wrote in the lawsuit.

They asked the court to vacate the rules, according to the document.

Bryan Corbett, chief executive officer of the Managed Funds Association (MFA), said the rules will increase costs for investors and curb competition, he added.

The suit was filed in the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The other petitioners are the National Venture Capital Association, American Investment Council, Alternative Investment Management Association, National Association of Private Fund Managers and the Loan Syndications & Trading Association.

The suit is one of a growing number brought against Gensler's SEC. In a recent blow to the SEC, a judge panel ruled that the SEC was wrong to reject Grayscale Investments' proposed bitcoin ETF without explaining its reasoning.

Whenever you hear the private equity/ hedge fund industry accuse the SEC over overreach, you know the regulators are on to something.

So what are the implications of the SEC's proposed rule and that of the Australian regulator?

Chris Addy, founder and CEO of Castle Hall Diligence has been very active on LinkedIn recently covering the implications of the SEC's private fund rule.

He began with this post:

So what will be the implications of the private fund rule?

When I read the first draft of the private fund rule, my first reaction was that the SEC must have subpoenaed a few hundred operational due diligence reports written by knowledgeable ODD practitioners across the industry. The three foundational pillars of the final rule - a lack of transparency, the presence of conflicts of interest, and a lack of governance over private market investments - are at the core of numerous ODD findings written by Castle Hall as well as by our peers in the consulting space and equally in-house ODD teams.

So, on the one hand...here in the ODD community you could say that we would be quite happy for the status quo to continue, as problems with transparency, conflicts and governance are a gift that keeps giving for ODD. After all, if all hedge fund and PE operational, structural and governance problems went away (....and if everyone was honest, and no one ever made an honest mistake) - then there would be no need for ODD.

But, of course, the governance, risk and compliance specialists who manage operational due diligence do tend to be guided a little more by ethics and integrity, as compared to billable hours.

There are many implications to the private fund rule. Castle Hall has identified 10 likely outcomes as investors - large and small - receive new levels of transparency over their alternative asset investments. Our list is informed by our work conducting diligence on several thousand asset manager - so we do have quite a good idea where a lot of the skeletons are buried, so to speak. And, just as importantly, our thoughts are guided by our experience seeing the governance and decision making structures within many large institutional investors.

We will be working on more detailed commentary given the scope of many of these issues, but I will use LinkedIn to highlight some quick thoughts on each of the points. I'm also very interested to get your views in the comments section (and happy to chat via direct message).

The first, which I'll address tomorrow, is valuation.

The quarterly reporting requirement will force PE managers to take the valuation process much more seriously. To date, lagged valuations have often been seen as a feature, not a bug of PE investing by many PE market participants. Unduly lagged and over optimistic valuations which are slow to reflect drawdowns will not be acceptable in an official quarterly performance report delivered as a requirement of the 1940 Act.

Chris followed up with this post:

Private Fund Rule - whose money is it?

First, I'd like to thank many industry participants for their supportive comments as I respond to the private funds rule.

Before I get to my list of 10 implications of the rule, I'd like to make an introductory comment.

My perspective is orientated to the needs and objectives of the global pension industry. The starting point of my "slant" on the private funds rule is that the growth of the alternative assets industry over the past 20 years has been overwhelmingly driven by allocations from pension and retirement capital. Globally, gatekeeper investors now aggregate the pension assets of (easily) more than 100 million pensioners (contributors and beneficiaries) worldwide.

As just one example, the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, with nearly C$600billion in net assets, is the steward - and must act in the best interests of - the pension assets of more than 21 million Canadians. (Here in Quebec our 8 million pensions are instead invested with La Caisse de Depot et Placement du Quebec, or CDP.)

Similarly, almost 16 million Australians have superannuation accounts, many of which are held by gatekeepers such as Australian Super, the Australian Retirement Trust, REST, CBUS etc. (I would note that one thing that Australia has which Canada does not is a national, universal pension regulator which holds all Aussie Super Funds to the same standards as "Registerable Superannuation Entities").

In Europe we have numerous governmental and private pension pools: in the Netherlands, ABP has 3 million participants alone. Then we have the sovereigns - 5.5 million Norweigans benefit from the Government Pension Fund. In the US we have State and occupational pension funds (think CalPERS etc), which the SEC states hold the assets of more than 26 million Americans.

I was first exposed to hedge funds back in 1994 when I moved to Bermuda as a newly qualified accountant. Back then, hedge funds were the "secret club of the super rich", which you could find pretty much only in the Caribbean and Geneva. (And I have subsequently worked for a Swiss private bank!)

If "private funds" - in the SEC's terminology - were truly private, then what ultra high net worth individuals and private foundations do with their own money is no one's business but their own.

But, "private funds" are not private - they are emphatically public in that their investors now include tens of millions of members of the public across all major countries. That means that the activities of hedge funds, PE, VC, real estate, infra and credit managers now fall into the domain of public policy: and with ageing populations, funding retirement is one of the biggest public policy issues out there. Against this background, issues of a lack of transparency, conflicts of interest and inadequate governance can impact the retirement outcomes of millions.

The starting point, then, is to remember whose money it is.

He then followed up with this post on the private fund rule and valuations:

The Private Fund Rule: Implication 1 - Valuation

In my list of 10 implications of the SEC’s new private fund rule, I’m starting with what I think will be the biggest - although the issue, valuation, is not the most high profile (the organisations suing the SEC seem more wound up about pass through fees and keeping side letters secret. I’ll get to those points later in the list!)

The rule requires every manager of a private fund to produce a quarterly statement which lists performance and fees. Different presentations / calculation methodologies are prescribed for liquid versus illiquid funds. The end result will be that allocator investment and then investor accounting, governance, risk and compliance teams will receive standardized performance disclosures for every (US private fund) investment, every quarter, within 45 days.

This is not a game changer for hedge funds which have always had monthly NAVs (or up to daily for liquid alt products). But for private markets, the implications are extensive.

The core change is that private equity / venture capital GPs will now have to prepare an official, quarterly performance report.

GPs will no longer be able to present unofficial, vague estimates which “don’t really matter”. Now, the SEC will be able to bring enforcement actions against a private market manager who has weak valuation policies, procedures and documentation if they deliver valuations which do not reflect any declines in portfolio asset values on a timely basis.

What the SEC is really doing is going to the heart of one of the unspoken tenets of private equity investing - which is, it is important to note, implicitly welcomed by many private market investors. The private asset industry has, to date, accepted that PE / venture / real estate pricing is lagged and doesn’t “react” as quickly as public markets.

While this may fall into the category of an “emporer has no clothes” comment, I’ll say it anyway - a lagged valuation is simply a valuation which is wrong.

Lagging valuations impact the industry in three dimensions:

1) GPs say “no one cares” about interim valuations, as no one can redeem from a closed ended vehicle.

2) GPs say they are unable to calculate valuations on private assets on a timely basis, with valuations being lagged somewhere between 90 and 270 days.

3) The real elephant in the room - institutional investors with high allocations to private assets have reported better performance than those with higher allocations to public equities and bonds in 2022 and 2023.

Have private assets provided true protection of value as interest rates increase, inflation rises, we have a European war, and in real estate the post pandemic effects of work from home? Or is at least some of that performance differential due to the fact that private asset valuations do not react as quickly - and to the same magnitude - as public market assets?

I’ll explore these 3 themes in my next posts.

And in his latest post on private market valuations, Chris notes this:

The Private Fund Rule: Implication 1 - Valuation.Alright, let me begin by thanking Chis for having the chutzpah to post his thoughts publicly on LinkedIn.

"No one cares" about interim valuations?

I mentioned in my last post that one of the three issues which drive the private markets' space reliance on lagged valuations is that "no one cares" about interim valuations. This is, firstly, as managers / GPs argue that investors cannot redeem (there is no trading NAV for redemptions in a closed ended fund). I've also heard multiple, "old school" GP's dismiss interim, mark to market valuations as pretty much "meaningless" as they do not represent a transactional value.

I disagree - interim valuations are material and significant.

1) Many public pensions post their performance quarterly. This performance is high profile, reported on by journalists and reviewed by members. To take one of the Canadian plans, OMERS, their press release of August 16 discusses their performance in the first half of the year, with PE up 1.9% and real estate down 0.2%.

As underlying PE / real estate funds step up to produce more reliable, structured valuations each quarter as now required by the SEC, then the performance reported by pension gatekeepers such as OMERS will equally become more reliable.

2) Interim valuations provide more data points to support the actuarial process which determines whether a pension plan is under / over funded.

3) Critically, interim valuations drive investor transactional behaviour. At present, many PE investors see a "denominator" effect as their PE funds are now a greater percentage of their portfolio due to falls in public equities (and also a sharp drop in PE distributions). Let's face it - at least part of that denominator effect is the result of lagged valuations which have not adjusted PE / real estate valuations down - yet endowments and pensions are transacting based on the lagged, likely over-stated valuations.

4) Interim valuations are an input into the value of secondary transactions.

5) Interim valuations are used as the basis of hedging (fx and rates)

6) Interim valuations form part of the performance history of prior funds which will be used to market for the next vintage.

7) Finally, in some markets - notably Australia - underlying pensioners can transact based on interim valuations. Thanks Craig Roodt for making that point in a comment on my last post.

These factors all support the need for a structured, formal reporting of quarterly PE / Real Estate fund valuations.

Next question - is the SEC justified in asking for valuations within 45 days?

I agree with Chris on many but not all his points.

First and foremost, I'm a stickler for more transparency.

As Chris notes, pension funds manage money from captive clients.

The fact that ordinary working stiffs are paying forced contributions to public pensions to enrich Ken Griffin, Steve Cohen, David Tepper, Izzy Englander, Stephen Schwarzman, Henry Kravis, Marc Rowan, David Bonderman, John Grayken, Daniel D'Aniello, Orlando Bravo and so on, is reason enough to demand full transparency on fees and more.

"But Leo, these are powerful people managing institutional money."

And? So what? They all started off hustling for a living and didn't get to where they are without the help of US and global public pension funds.

Keep that in mind the next time your read the Forbes list of billionaires and see them on it.

Back to Chris Addy's comment on valuations.

Fact is private markets are not marked to market but their exits are affected when the stock market goes down as are valuations when rates go up.

The lagged valuation or stale pricing in private markets is well known.

Typically, this lagged valuation is criticized by public market fund managers but when it comes to pension plans, it acts as a shock absorber of sorts.

Let me explain, let's say in six weeks, PE funds are forced to provide quarterly valuations and fee reports. Will they mark these assets down if their public market counterparts are getting roiled?

Probably not a huge mark down because it's not in their interest but they will be forced to mark these assets down more frequently.

This can set off a whole chain reaction and we need to carefully think of these implications.

Let's say pension funds marked down private real estate holdings in 2022 in line with how REITs performed last year:

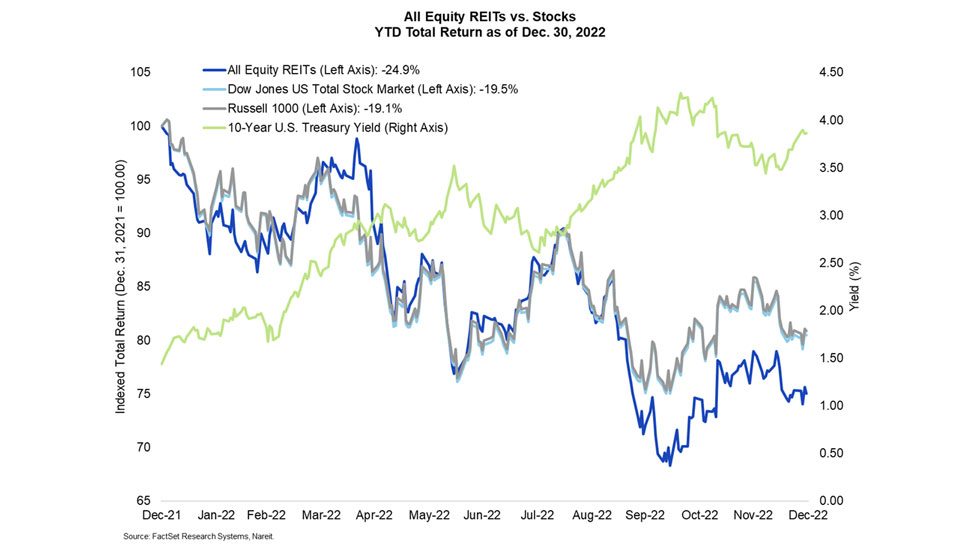

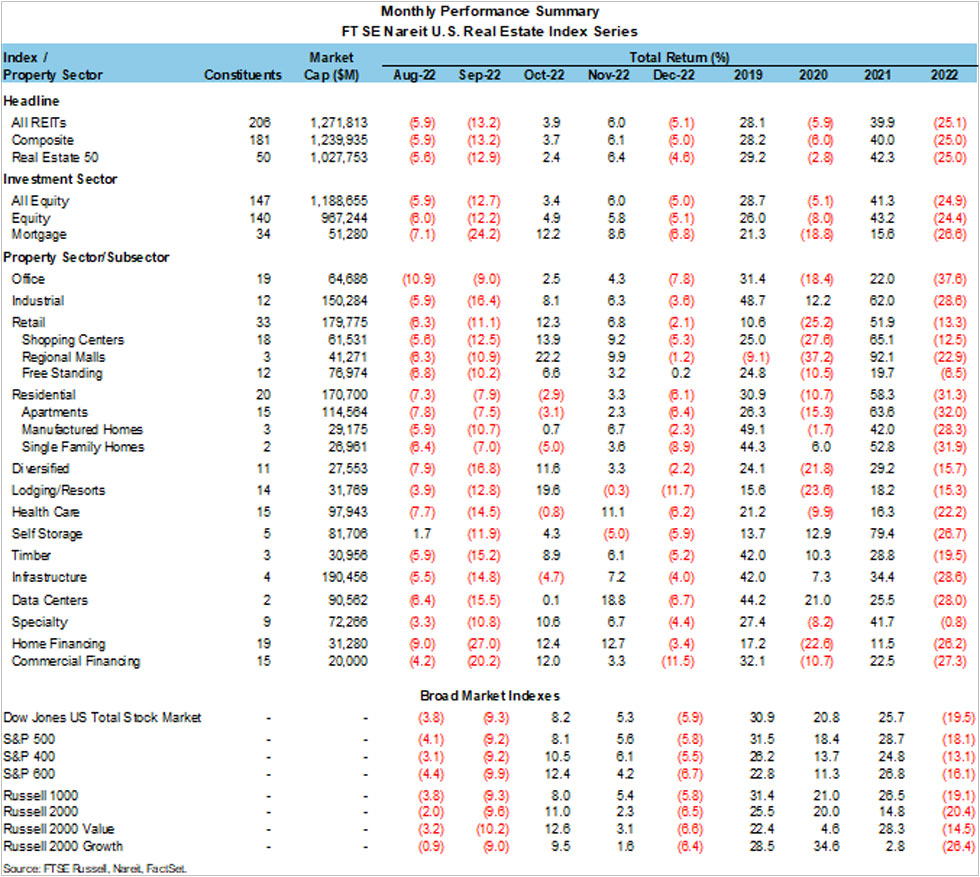

REITs underperformed broader markets in 2022, as the FTSE Nareit All Equity REITs Index posted a total return of -24.9% and the FTSE Nareit Equity REITs Index returned -24.4%. On a yearly basis this was the steepest decline since 2008, when All Equity REITs declined 41.1%. Mortgage REITs also declined in 2022, as the FTSE Nareit Mortgage REITs Index fell 26.6%. Broader markets were also negative, as the Russell 1000 and Dow Jones U.S. Total Stock Market Index fell 19.1% and 19.5%, respectively. Over the course of 2022, the yield on the 10-year Treasury rose 243 basis points to end the year at 3.9%. After initial optimism as the pace of monetary policy tightening slowed in December, markets have priced in rates remaining higher for longer, as the Federal Reserve remains decidedly hawkish.

All property sectors were negative in 2022, led by specialty at -0.8%, retail at -13.3%, and lodging/resorts at -15.3%. Office lagged all other sectors with a total return of -37.6%, followed by residential at -31.3% and infrastructure at -28.6%. Mortgage REITs were also down sharply, with returns of -26.2% for home financing mREITs and -27.3% for commercial financing mREITs.

Now, as you can read, there were some serious losses in public real estate holdings last year but when you look at the performance of Real Estate at Canada's large pension funds, nobody reported anywhere close to double digit losses in real estate.

They will argue the composition of their portfolio isn't exactly the same, they are more diversified geographically and by sector, focusing more on logistics/ industrial properties and niche markets like lab properties and data centers but they still have roughly 30% or more in offices and retail.

I recently covered the mid-year results of OTPP, OMERS, CDPQ and AIMCo and noted real estate portfolios are being marked down as cap rates rise but are they being marked down significantly?

No, not yet.

Same goes for Private Equity and to a lesser extent Infrastructure holdings.

When 40-50% of your assets are in private markets, it gives you a buffer in case you experience a really bad year in stocks and bonds like 2022.

And when your strategy is focused on adding value in private markets by co-investing with top private equity funds to gain access to larger deals and mitigating fee drag, it's not in your interest to rock the boat on fees and transparency.

Moreover, when your compensation is based on four or five-year added value, it's definitely not in your interest to mark down private markets in one fell swoop.

But there is another reason why private markets are not valued quarterly, they move more with the broad economy and it's better to value them over a longer period of time.

And they do provide a shock absorber of sorts to valuations of public markets which are much more volatile, especially in the zero interest rate world.

And this volatility absorber works well for pension plans looking to stabilize their contribution rate.

So, from an actuarial point of view, I'd argue it's better not to value private markets every quarter.

Anyways, there's a lot to consumer and ponder here.

Keep your eyes out for Chris Addy's subsequent posts on LinkedIn here.

I will likely have to revisit this comment.

One thing I didn't cover is leverage.

Canada's large pension funds issue debt and get rated by the rating agencies.

That's why they produce semi-annual and/ or quarterly results (in case of CPP Investments, it's by law).

The use of leverage which CalPERS recently implemented allows pensions to seize opportunities in private markets when they arise without forced selling of other assets at the wrong time.

It's also a more efficient use of capital.

That's one area where I don't agree with Chris and the "denominator effect" he talks about above.

It's a bit more complicated and nuanced as is this discussion on forcing PE funds to value their assets every quarter.

In general, I'm all for this idea but it needs to be done carefully and knock-on effects need to be considered (and there are plenty).

Aright, let me wrap it up there, email me at LKolivakis@gmail.com if you have any pertinent comments to add on this subject.

Below, hedge funds and private equity firms face new requirements to disclose fees and restrictions on giving investors special treatment under sweeping rules the US Securities and Exchange Commission plans to impose on Wednesday (two weeks ago). The five-member commission is set to vote Wednesday on the new rules. Bloomberg's Sonali Basak reports.

And Bryan Corbett, president and CEO at Managed Fund Association, joins 'Squawk Box' to discuss the MFA's problems over new private equity rules, the details in the rules, and more.

Comments

Post a Comment