New Math Hits Minnesota's Pensions?

Martin Z. Braun of Bloomberg reports, New Math Deals Minnesota’s Pensions the Biggest Hit in the U.S. (h/t, Suzanne Bishopric):

But while Kentucky, Illinois, and New Jersey have well-known public pension problems, other states are also on the verge of seeing their pensions collapse, either because of years of neglect or more likely, because the new pension math (new GASB rules) is forcing them to use a much lower discount rate to determine their future liabilities.

I have already discussed whether these new regulations will sink pensions here and here, and while some critics claim these new rules are too stringent, there's no denying using a 7% or 8% assumed rate-of-return to determine future liabilities is way too lax and rosy, significantly understating the true debt profile of US public pensions.

Remember, pensions are all about managing assets AND liabilities. If liabilities are skyrocketing because interest rates have declined and will stay at ultra-low record levels for years, then to be using a rosy assumed investment rate to discount future liabilities is simply not acceptable and borderline fraud.

And since the duration of liabilities is a lot bigger than the duration of assets, then no matter how well investments do, pension deficits will keep widening as interest rates decline. This effectively is the death knell for chronically underfunded US public pension plans.

Also, lowering the discount rate means liabilities will explode up, and this has all sorts of policy implications because it effectively means more and more of the public budget will need to go to service these pensions, cutting municipal and state services elsewhere.

And if the situation gets really bad, taxpayers will be called upon to shore these chronically underfunded public pensions, something which isn't politically palatable in today's economy where many private sector taxpayers are stretched, trying to save a buck for their own retirement.

More worrisome, from Kentucky to New Jersey, to Illinois to Minnesota, America's public pensions are crumbling and they're not bulletproof. If one by one, large US public pensions collapse, they could potentially fuel the next crisis.

One thing is for sure, America and the world hasn't properly addressed the ongoing pension crisis which is deflationary as more and more workers retire with little to no savings and are at risk of succumbing to pension poverty.

This is why I'm highly skeptical that central banks should adopt zero rates now. No doubt, we need inflation but this policy might aggravate an already dire pension situation and lead to more deflation.

I don't know, what do you think? Every time I write on these pensions at risk of collapse, it depresses me because I know some poor worker or retiree is going to get a rude awakening in the future when their chronically underfunded pension has no choice but to increase the contribution rate and/ or cut benefits to shore up their plan.

Below, an older clip (2015) where Bill Hudson of WCCO CBS reports Minnesota Teamsters have been told to brace for huge cuts in their monthly pension benefits.

Unfortunately, Minnesota's new pension math and years of neglect will mean hundreds of thousands of public-sector retirees will likely join their ranks in the future.

Update: Bernard Dussault, Canada's former Chief Actuary, shared this with me after reading this comment:

Minnesota’s debt to its workers’ retirement system has soared by $33.4 billion, or $6,000 for every resident, courtesy of accounting rules.In my last comment, I looked at whether Kentucky's pensions are finished, and stated that years of neglect, incompetence, cover-ups, corruption and lack of governance have irrevocably jeopardized the future of public pension plans in that state.

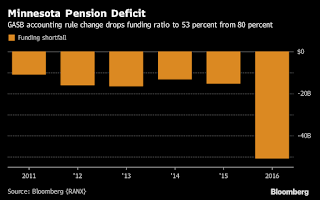

The jump caused the finances of Minnesota’s pensions to erode more than any other state’s last year as accounting standards seek to prevent governments from using overly optimistic assumptions to minimize what they owe public employees decades from now. Because of changes in actuarial math, Minnesota in 2016 reported having just 53 percent of what it needed to cover promised benefits, down from 80 percent a year earlier, transforming it from one of the best funded state systems to the seventh worst, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

“It’s a crisis," said Susan Lenczewski, executive director of the state’s Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement.

The latest reckoning won’t force Minnesota to pump more taxpayer money into its pensions, nor does it put retirees’ pension checks in any jeopardy. But it underscores the long-term financial pressure facing governments such as Minnesota, New Jersey and Illinois that have been left with massive shortfalls after years of failing to make adequate contributions to their retirement systems.

The Governmental Accounting Standards Board’s rules, ushered in after the last recession, were intended to address concern that state and city pensions were understating the scale of their obligations by counting on steady investment gains even after they run out of cash -- and no longer have money to invest. Pensions use the expected rate of return on their investments to calculate in today’s dollars, or discount, the value of pension checks that won’t be paid out for decades.

The guidelines require governments to calculate when their pensions will be depleted and use the yield on a 20-year municipal bond index to determine costs after they run out of money.

The Minnesota’s teachers’ pension fund, which had $19.4 billion in assets as of June 30, 2016, is expected to go broke in 2052. As a result of the latest rules the pension has started using a rate of 4.7 percent to discount its liabilities, down from the 8 percent used previously. As a result, its liabilities increased by $16.7 billion.

The worsening outlook for Minnesota is in line with what happened nationally. Pension-funding ratios declined in 43 states in the 2016 fiscal year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. New Jersey had the worst-funded system, with about 31 percent of the assets it needs, followed by Kentucky with 31.4 percent. The median state pension had a 71 percent funding ratio, down from 74.5 percent in 2015.

While record-setting stock prices boosted the median public pension return to 12.4 percent in 2017, the most in three years, that won’t be enough to dig them out of the hole.

Only eight state pension plans, in Minnesota, New Jersey, Kentucky and Texas, used a discount rate “significantly lower" than their traditional discount rate to value liabilities, according to July report by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

“Because of that huge drop in the discount rate under GASB reporting, their liabilities skyrocket," said Todd Tauzer, an S&P Global Ratings analyst. “That’s why you see that huge change compared to other states.”

Public finance scholars at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center have found “considerable variance" in how states were applying the new standards. In Illinois, for example, despite the state’s poor history of funding its plans, actuaries project they won’t run of money until 2072.

In Minnesota lackluster returns and years of shortchanging have taken a toll. The state’s pensions lost 0.1 percent in fiscal 2016.

But other factors also helped boost Minnesota’s liabilities: Eight of Minnesota’s nine pensions reduced their assumed rate of return on their investments to 7.5 percent from 7.9 percent, while three began factoring in longer life expectancy.

Minnesota funds its pensions based on a statutory rate that’s lower than what’s need to improve their funding status. School districts and teachers contribute about 85 percent of what’s required to the teacher’s pension, according to S&P Global Ratings.

“It’s woefully insufficient for the liabilities," said Lenczewski, the director of Minnesota’s legislative commission on pensions. “You just watch this giant thing decline in funding status."

But while Kentucky, Illinois, and New Jersey have well-known public pension problems, other states are also on the verge of seeing their pensions collapse, either because of years of neglect or more likely, because the new pension math (new GASB rules) is forcing them to use a much lower discount rate to determine their future liabilities.

I have already discussed whether these new regulations will sink pensions here and here, and while some critics claim these new rules are too stringent, there's no denying using a 7% or 8% assumed rate-of-return to determine future liabilities is way too lax and rosy, significantly understating the true debt profile of US public pensions.

Remember, pensions are all about managing assets AND liabilities. If liabilities are skyrocketing because interest rates have declined and will stay at ultra-low record levels for years, then to be using a rosy assumed investment rate to discount future liabilities is simply not acceptable and borderline fraud.

And since the duration of liabilities is a lot bigger than the duration of assets, then no matter how well investments do, pension deficits will keep widening as interest rates decline. This effectively is the death knell for chronically underfunded US public pension plans.

Also, lowering the discount rate means liabilities will explode up, and this has all sorts of policy implications because it effectively means more and more of the public budget will need to go to service these pensions, cutting municipal and state services elsewhere.

And if the situation gets really bad, taxpayers will be called upon to shore these chronically underfunded public pensions, something which isn't politically palatable in today's economy where many private sector taxpayers are stretched, trying to save a buck for their own retirement.

More worrisome, from Kentucky to New Jersey, to Illinois to Minnesota, America's public pensions are crumbling and they're not bulletproof. If one by one, large US public pensions collapse, they could potentially fuel the next crisis.

One thing is for sure, America and the world hasn't properly addressed the ongoing pension crisis which is deflationary as more and more workers retire with little to no savings and are at risk of succumbing to pension poverty.

This is why I'm highly skeptical that central banks should adopt zero rates now. No doubt, we need inflation but this policy might aggravate an already dire pension situation and lead to more deflation.

I don't know, what do you think? Every time I write on these pensions at risk of collapse, it depresses me because I know some poor worker or retiree is going to get a rude awakening in the future when their chronically underfunded pension has no choice but to increase the contribution rate and/ or cut benefits to shore up their plan.

Below, an older clip (2015) where Bill Hudson of WCCO CBS reports Minnesota Teamsters have been told to brace for huge cuts in their monthly pension benefits.

Unfortunately, Minnesota's new pension math and years of neglect will mean hundreds of thousands of public-sector retirees will likely join their ranks in the future.

Update: Bernard Dussault, Canada's former Chief Actuary, shared this with me after reading this comment:

As you may already well know, my proposed financing policy for defined benefit (DB) pension plans holds that solvency valuations (i.e. assuming a rate of return based on interest only bearing investment vehicles as opposed to the return realistically expected on the concerned actual pension fund) are not appropriate because they unduly increase any emerging actuarial surplus or debt of a DB pension plan.I thank Bernard for sharing his wise insights on this subject.

Nevertheless, while assuming a realistic rate of return as opposed to a solvency rate would decrease the concerned USA DB pension plans' released debts, any resulting surplus would not appear realistic to me if the assumed long-term real rate of return were higher than 4% for a plan providing indexed pensions.

Comments

Post a Comment