Big Trouble at UK's Universities Superannuation Scheme?

Students returning to UK university campuses this month face further disruption, including walkouts by their lecturers, after the sector’s main union said industrial action over pension cuts was “inevitable”.

The University and College Union (UCU) issued the warning on Tuesday after a committee made up of employer and union representatives backed controversial pension proposals put forward by Universities UK (UUK), which represents the institutions, to ease an estimated £14bn-£18bn funding shortfall in the Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS), the sector’s main retirement fund.

UCU foreshadowed a ballot for industrial action in the autumn as it on Tuesday emailed 50,000 members inviting them to a mass meeting to discuss the proposals, which it claims will see a typical lecturer lose about a third of their guaranteed pension benefits.

“Employers represented by Universities UK (UUK) have today voted to implement a set of regressive USS pension proposals that will reduce member benefits, discourage low-paid and insecurely employed staff from joining USS, and threaten the viability of the scheme as a whole,” said Jo Grady, UCU general secretary.

“Employers have failed to support alternative compromise proposals put forward by UCU, drawn up under the constraints of a flawed 2020 valuation of the scheme. Unless employers allow for a rapid consultation on our proposals with a view to revoking their decision today, the path looks inevitably to lead to industrial action.”

The employer and employee representatives on the USS Joint Negotiating Committee (JNC) were evenly split on the proposals, with the casting vote in favour of the reforms cast by the independent chair. UUK claimed its proposals — which include slowing down the rate at which pensions build before retirement, and capping inflation increases at 2.5 per cent, would help employers and employees avoid significant increases in their contributions.

Under the UUK plan, employer and employee contribution rates will remain at 21.1 per cent and 9.6 per cent of employee salary respectively.

The USS trustees this year warned that contribution increases of up to 25 per cent of salary may be required to keep the defined benefit pensions, which pay out a guaranteed sum each year tied to the employee’s salary, in their current shape.

“The employers’ proposal sees a significant element of defined benefit retained while preventing unaffordable contribution levels,” UUK said.

“USS’s formal assessment of the scale of the deficit means that no change is not a viable option. We understand that the benefit changes passed by the JNC will be unwelcome for scheme members, but the huge increases in contributions required to keep benefits the same are unaffordable for most members and employers.”

UUK said UCU had decided not to put a counter proposal to the vote. “We repeatedly said to UCU during the JNC process that UUK would be willing to put UCU’s suggestions to employers to seek their views and that offer still stands,” said UUK.

UCU said the vote was passed ahead of UUK considering alternative UCU proposals and calls from the union for a month-long extension to negotiations to allow both employers and pension members to be consulted.

Josephine Cumbo also tweeted on this issue:

NEW: Proposed cuts to pension benefits for hundreds of thousands of UK university sector staff will see a worker earning under £40k p/a with 12% less retirement income, according to UUK, the university employer body.

— Josephine Cumbo (@JosephineCumbo) September 1, 2021

This estimate assumed inflation does not rise above 2.5%.

UUK says the alternative to its pension proposal may see members subjected to steep increases in their #pension contribution rates from 13.6% and 18.6% of salary (compared with 9.6% now) – which would hit take-home pay and may price many out of the scheme.

— Josephine Cumbo (@JosephineCumbo) September 1, 2021

NEW: The Russell Group of Universities has issued a statement on the #USSpensiondispute

— Josephine Cumbo (@JosephineCumbo) September 1, 2021

“We recognise this is a challenging situation for staff and making changes to contribution rates or future benefits is never easy, but it is only done when absolutely necessary." pic.twitter.com/isBGQSYtfD

NEW: A mass meeting of university sector union members will take place this Friday via Zoom, to discuss strike action over #pension cuts.

— Josephine Cumbo (@JosephineCumbo) September 1, 2021

The University and College Union has invited 50,000 members to the online meeting. #USS

#UCU delegates are to decide on September 9 what type of industrial action university members - including academics and other staff - will take on university campuses over #USSpensiondispute.

— Josephine Cumbo (@JosephineCumbo) September 1, 2021

NEW:University employers say they will still consider "alternative benefit structures and formulations", provided they are "viable, affordable & implementable".

— Josephine Cumbo (@JosephineCumbo) September 1, 2021

The statement comes after the UK university sector union warned industrial action over pension cuts was "inevitable" pic.twitter.com/8vAImaLbtx

Of course, I couldn't help but reply on Twitter:

This is terrible. The UK can learn a lot from the Canadian model of pension management and governance https://t.co/0fhyPGSWYS

— Leo Kolivakis (@PensionPulse) August 31, 2021

Not surprisingly, the University and College Union (UCU) is not pleased, putting out this press release on employers forcing through plans to cut university retirement benefits:

UCU says industrial action in universities is now 'inevitable' after employer body Universities UK (UUK) voted to push ahead with its proposals to cut thousands of pounds from the retirement benefits of university staff.

At a meeting of the Universities Superannuation Scheme's (USS) Joint Negotiating Committee (JNC) employers voted for its package of cuts ahead of considering alternative UCU proposals and calls from the union for a month-long extension to negotiations to allow both employers and pension members to be consulted.

UCU's proposals would have delivered higher benefits in return for lower contributions than those put forward by employers. For the first time, they would have provided a secure pension for staff on low pay and insecure contracts who are currently priced out of the scheme. The proposals were intended to be a fair and short-term resolution to the flawed USS scheme valuation, which was carried out at the start of the pandemic when markets were crashing.

However, employers repeatedly refused to agree to a small increase in their own contributions. They also refused to provide the same level of employer 'covenant support' for UCU's alternative proposals as they were willing to provide for their own.

Now, with UUK's proposals voted through, those members who can afford to stay in USS will face significant cuts to their retirement income.

A typical member of the USS scheme on a £42k lecturer's salary, aged 37, will suffer a 35% loss to the guaranteed retirement benefits which they will build up over the rest of their career.

UCU says the employers' changes will threaten the viability of the scheme, with more and more staff likely to decide to leave the scheme in the face of cuts to benefits and increases in contributions.

In June, delegates to UCU's annual Congress voted to ballot for industrial action if employers did not rethink their proposals. The union has today emailed over 50,000 members in USS institutions calling them to a mass member meeting, where the union will outline what next steps will be, and how they should start to prepare for balloting and strike action.

The union says the only realistic way to avoid strike action at this late stage is for employers to carry out a rapid consultation on covenant support and the UCU proposals.

UCU general secretary Jo Grady, said:

'Employers represented by Universities UK (UUK) have today voted to implement a set of regressive USS pension proposals that will reduce member benefits, discourage low paid and insecurely employed staff from joining USS, and threaten the viability of the scheme as a whole.

'Employers have failed to support alternative compromise proposals put forward by UCU, drawn up under the constraints of a flawed 2020 valuation of the scheme. Disappointingly, UUK did not support calls from UCU for a new valuation, despite the overwhelming case for one, and refused to allow for time to consult universities on UCU's proposals, instead choosing to vote through their cuts.

'UCU's proposals were far superior to those of UUK, delivering higher benefits and reducing contributions for staff. They provided flexibility and for the first time in the scheme's history guaranteed benefits for the thousands of low-paid and insecurely employed staff who are currently priced out of joining USS. However, the proposals did not win the agreement of employers, who failed to commit to providing the same covenant support as they did for their own proposals.

'UCU's proposals would have provided a safe and equitable stop-gap solution until a new valuation is carried out, which should be at the earliest opportunity. Sadly employers have chosen to use a flawed valuation conducted at the start of the pandemic to rush through cuts to members' pensions. Unless employers allow for a rapid consultation on our proposals with a view to revoking their decision today, the path looks inevitably to lead to industrial action - and that is the responsibility of UUK.'

With

the

Universities Superannuation Scheme's (USS) funding shortfall estimated between £14bn-£18bn,

it's no wonder employers are proposing to hike the contribution rate and cut benefits.

Without blaming UCU or UUK, you have to wonder what exactly led to this funding shortfall? Is it artificially low valuations from the 2020 fallout or is it something structural?

And by structural, I mean really poor governance and lack of risk sharing which led to this situation (ie. are they a jointly sponsored plan and have they adopted conditional inflation protection?).

I have no clue but looking at the Universities Superannuation Scheme's (USS) website, it looks like a very well managed plan.

In fact, at the end of July, USS published a Report and Accounts covering 'an extraordinary year':

- £82.2bn – total value of assets under management

- 9.75% – average per annum investment return for the defined benefit fund, over five years

- £66 million – how much lower USS’s annual investment management costs were than its peers

- £15.2bn – estimated Technical Provisions deficit

- 88% – of employers who rate their relationship with USS as good/very good

Universities Superannuation Scheme has published its annual Report and Accounts, covering the financial year to 31 March 2021.

Investment returns for the scheme’s defined benefit (DB) assets averaged 9.75% pa over the five years to 31 March 2021, helping the DB fund to increase by £30.8bn in that time.

By managing the majority of its investments in-house, USS saves money compared to the expense of external management.

According to the latest independent analysis, USS’s annual investment management costs were £66 million lower than its peers1.

In June 2020, USS Investment Management announced its first exclusions policy. USS has since stated its ambition to be ‘Net Zero’ for carbon by 2050, if not before.

At 31 March 2021, total assets under management were £82.2bn (2020: £67.6bn). Its DB fund stood at £80.6bn, while its defined contribution (DC) assets totalled £1.6bn.

Its estimated DB funding deficit stood at £15.2bn on a Technical Provisions basis, based on monitoring of key financial measures since the 2018 valuation (2020: £12.9 billion). The funding ratio on the same basis was static at 84%.

- USS’s membership grew in 2020/21 by more than 15,000, from 459,714 to 476,002 (203,995 active, 194,044 deferred, 77,963 retired).

- All members of USS are part of the scheme’s DB section; around 91,000 members now hold supplementary DC assets with the scheme, which were worth £1.6bn at 31 March 2021 (2020: £1.1bn).

Bill Galvin, USS Group Chief Executive, said: “Through an extraordinary year, we have worked hard to deliver the best outcomes possible for members. Service levels have remained very strong, through all the challenges. Our asset values have grown by £30bn over five years, and our operating model continues to ensure we manage our assets at a cost lower than our peers.

“But the value of the inflation-protected pensions promised to our members has also soared, and so our funding ratio remains static. We’re working exceptionally hard with our stakeholders on the changes required to ensure the scheme’s funding of past promises and future benefits is appropriate and balances the interests of all members.”

Dame Kate Barker, Chair of the USSL Trustee Board, said: “Despite the strong rebound in financial markets supported by concerted government and central bank actions, we still face major challenges in dealing with the wide‑ranging financial impacts of the Coronavirus pandemic – in addition to the pressures the scheme was already under. Over the coming months we will continue to engage with Universities UK, University and College Union and The Pensions Regulator to find the best way forward.

“Whatever circumstances arise, I am convinced that USS has the leadership, the principles and the professionalism to deliver secure pensions and first-class services to our members.”

View the latest updates on the 2020 valuation.

Now, an 84% funded status isn't the end of the world (most large US state pensions would be perfectly happy with that funded status) but it is below the fully funded status that Canada's large pension plans are delivering.

I would need to know more details about the USS plan, like has it implemented conditional inflation protection, is it a jointly sponsored plan, etc.?

One thing that did catch my attention, however, is this press release from July 22 explaining their central projections for future investment returns:

We are currently holding a full valuation to establish how we plan to pay the benefits promised to our members over the coming decades. To the extent we plan to rely on uncertain investment returns, the process involves trying to predict how financial markets might perform over time. Relying solely on ‘guaranteed’ investment returns would be very expensive because of the very low yields available from ‘safe’ assets like UK government bonds (gilts).

My earlier article explained the difference between our expected investment returns and our prudent assumptions. In this article, I explain how the former have changed over the past 12 months – and why.

USS Investment Management (USSIM) has built proprietary models to produce central projections for long-term returns from a wide range of asset classes. These projections are one of the inputs used in the analysis underlying both asset allocation decisions and scheme valuations.

The approach taken by USSIM is based on a decomposition of investment returns into ‘fundamental building blocks’. From a given set of starting market conditions, we apply high-level assumptions for how the building blocks might evolve. We make extensive comparisons between our projections, historical experience and projections from other providers to ensure our analysis and results provide a reasonable ‘best estimate’ assessment. Nevertheless, we recognise that any attempt to construct long-term forecasts is subject to a high margin of uncertainty, so we avoid placing excessive reliance on precise forecasts when building a robust investment strategy. It is also useful to construct alternative scenarios from the ‘best estimate’ and assess their likelihood and investment implications.

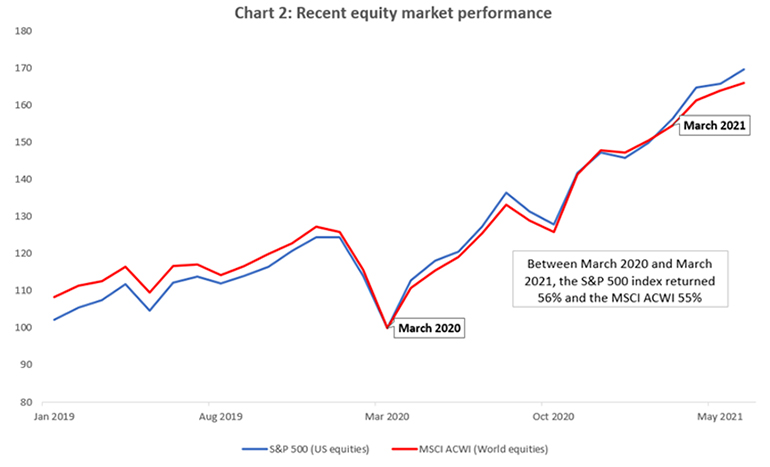

Since the advent of the pandemic in early 2020, financial markets have been on a wild ride. Equity markets plunged in the first quarter of 2020 before staging a remarkable comeback, with the S&P 500 index of US stocks delivering a return of almost 70% since March 2020.

Thanks to exceptional support from policymakers in the wake of the COVID-19 shock, bond yields touched their lowest levels in history over the course of 2020 (10-year gilt yields briefly traded below 0.1% in September 2020). This came in the wake of a relentless decline of nominal and ‘real’ bond yields over the past two decades. However, even bond yields did not manage to defy gravity and bounced back at remarkable speed in Q1 2021 as investors began to discount a more positive economic outlook.

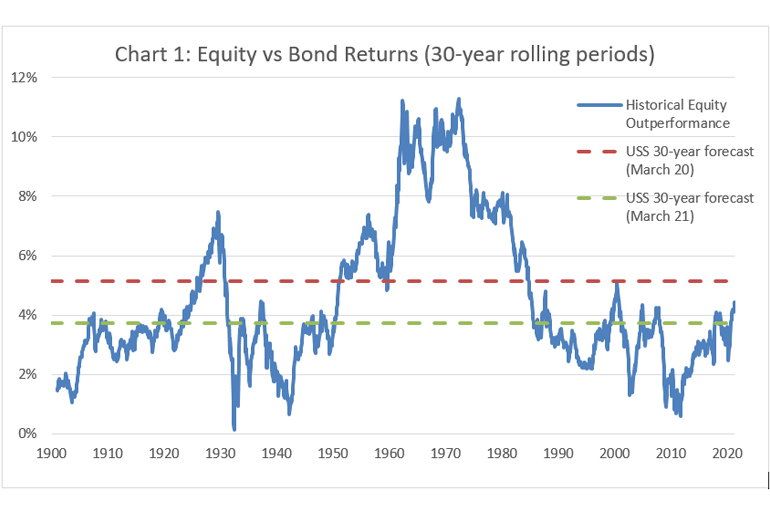

Episodes of wild financial market movements such as this are a feature of the long history for returns, as shown in the chart below, and help to highlight an important point: long term returns are highly variable and depend strongly on starting market conditions.

This is most obviously true for bond investors, where the initial bond yield tends to be a decent guide to subsequent long-term returns.

But it is also true for equities.

For example, an investor who had bought US equities in March 2009 – the lows of the financial crisis – and held for a decade would have realised a return roughly double that of an investor buying equities for 10 years in December 2007 before the 2008 market correction1. Our forecasts and subsequent market movements suggest that March 2020 was an attractive starting point for equity investors, at least relative to bonds, but March 2021 may be less opportune.

The fact that returns realised over decades can substantially change if you shift the start or the end point by a few months challenges the widely held view that equity returns are stable over very long horizons. As you can see in Chart 1 below, even returns realised over 30 years can vary from zero to double digit levels in annualised terms.

Source: USSIM, GFD June 2021. Note that history shown for US equities (S&P500) and US 10yr Treasury Bonds given data availability, but FBB forecasts are for a broad equity basket.

What is the significance of equity returns relative to bonds? Defined benefit (DB) pension schemes like USS promise members a set inflation-linked income for life in retirement, regardless of what happens to the economy in the future. So, a DB scheme’s liabilities are like corporate bonds: a contractual obligation to pay an income of X in the future “paid for” by a lump-sum received today, which is represented by the value of scheme assets in a DB fund.

We expect ‘riskier’ growth assets like equities to perform substantially better than low-risk, low-return assets like bonds over time. But the estimation of the extent of that outperformance comes with a substantial margin of error. Future returns are highly uncertain. In general, extrapolating historical returns offers a poor forecast.

Bonds represent the ‘price of certainty’. Growth assets can be reasonably expected to produce higher returns than bonds over the long run but there is no guarantee that this will always happen, even over very long horizons.

In March 2020, with bond yields low and equity prices depressed, our central forecasts were for higher equity outperformance over the next 30 years than had been seen in any 30-year historical period starting since the 1960s, despite a relatively weak economic outlook.

By March 2021, our central forecast had fallen back to be slightly below the historical outperformance of the last 30 years (as seen in Chart 1 above), after a good portion of the return advantage we forecasted in March 2020 had swiftly been realised over just one year thanks to global equity returns in excess of 50% (as shown in Chart 2 below).

From this perspective, March 2021 saw relatively ‘normal’ market conditions.

What about outright returns, which are more important for future pension contributions? How do our forecasts compare with history? We’ve looked at the expected outperformance of equities against bonds, which has fallen since March 2020 from strong to relatively typical levels. But in outright terms, our forecasts for both bonds and equity returns are now well below historic averages.

As mentioned, for bonds the starting yield tends to be a reasonable guide to future returns. Both in March 2020 and in 2021 bond yields were well below historic averages, which implies historically low outright returns for bonds – indeed future returns are likely to be negative after adjusting for inflation.

For equities the picture is more complex, but it is likely to be related. Despite forecasts for reasonably strong outperformance against bonds both as of March 2020 and as of March 2021, our return forecasts for equities were also below historic average returns. A combination of slower trend growth, relatively high corporate profit margins in sectors like technology stocks and elevated valuations (i.e. prices relative to fundamentals such as earnings, dividends or cash-flows) - arguably made possible by low interest rates - results in forecasts for equity returns that are low relative to history.

For a diversified portfolio across equity and bond assets of the type held by USS, this implies that future returns are likely to be below historical averages. Most other industry forecasters have reached a similar conclusion2 . Even Prof Dimson, Marsh and Staunton, who authored The Triumph of the Optimists in 2002, have pointed out in their latest yearbook3 that Generation Z is likely to experience much lower equity and bond returns than previous cohorts like Millennials and Generation X.

The future is unknowable. We are ultimately debating the ‘right’ answer to an unknowable question at a time of significant uncertainty. Could we all be wrong? Absolutely. It is certainly possible to depict a more positive scenario for equity markets. COVID-19 may represent a turning point in the global economy leading to a strong acceleration in the adoption of disruptive technologies, which in turn might lead to three ‘roaring’ decades of productivity gains. Equities would likely outpace bonds by a substantially larger margin than our ~4% ‘best estimate’ if this dynamic plays out. On the other hand, it is also possible that the build-up of inflationary pressures and policymakers’ action favouring a redistribution of the economic pie from capital to labour could lead to a very challenging environment for corporate profitability. Against this backdrop, equities may actually deliver a much lower outperformance than our ‘best estimate’ forecast, as has happened a number of times over the past 50 years.

So, there are risks – both upside and downside – to consider, but we believe our ‘best estimate’ provides a plausible assessment of equity and bond return prospects over the coming decades.

1 The US equity market realised a 15.9% annualised total return in the 10 years from March 2009 whereas over the 10 years from December 2017 it produced an 8.5% annualised total return (Source: Bloomberg)

2 For example JP Morgan Asset Management https://am.jpmorgan.com/gb/en/asset-management/adv/insights/portfolio-insights/ltcma/ and BlackRock https://www.blackrock.com/institutions/en-gb/insights/charts/capital-market-assumptions

3 The Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2021: https://www.credit-suisse.com/ch/en/about-us/research/research-institute.html

I love this analysis, every pension plan in the world should write similar "projections for future investment returns" going over not just stocks versus bonds, but for all their asset classes across public and private markets.

Anyway, I am not sure how the UCU-UUk battle will play out but from my perspective, USS is extremely well managed and you can learn more about it here and also look at its statement of funding principles.

On its governance, I note the following:

We (Universities Superannuation Scheme Limited) take care of the scheme and the Group Executive Committee looks after its day-to-day running.

We’re supported by our Advisory Committee which helps with difficult issues that arise under the Scheme Rules. And if the rules need changing, it'll need the support of the Joint Negotiating Committee who can also propose rule changes themselves.

We’re also regulated by The Pensions Regulator, whose responsibilities include protecting people's savings in workplace pension schemes and improving the way that those schemes are run. USS Investment Management Limited is regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

We have an Investment Committee which oversees the investment of the scheme’s assets and advises us on strategic matters relating to investments.

This is all so we can continue providing you with a valuable way to save for your future.

To find out more about our governance structure, have a look at the USS Group Governance Framework and the USSL Articles of Association.

Find out more about the Universities Superannuation Scheme Limited board and the USS Investment Management Limited board.

Alright, let me wrap it up there, if you have any more information on USS and the brewing battle between UCU and UUK, please email me at LKolivakis@gmail.com

Also, I am sure Barb Zvan and the Board at University Pension Pan (UPP) are looking closely at these developments making sure they will learn from problems that arose at USS.

Below, learn more about

the governance of the Universities Superannuation Scheme's (USS). As I stated, it looks like a very well run pension plan but I do hope they bolster it so that university and college teachers in the UK can enjoy their DB plan for many years to come.

Comments

Post a Comment